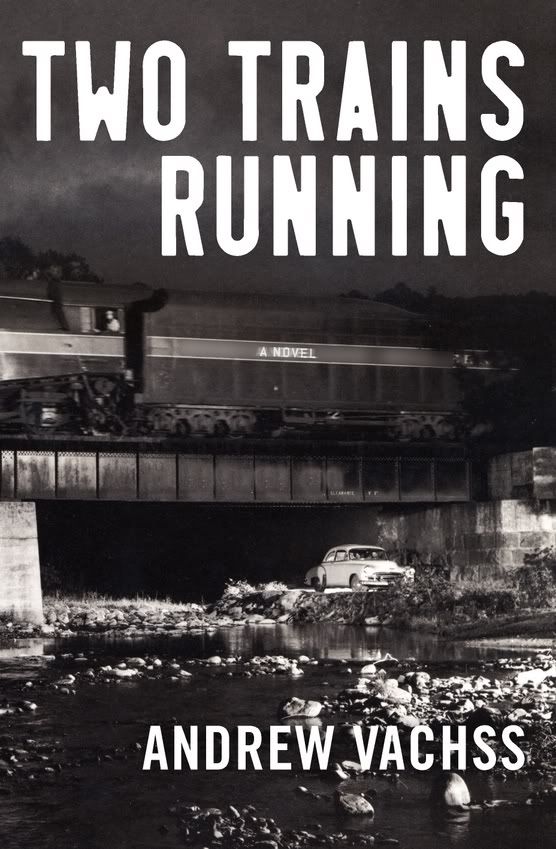

"Two Trains Running" - читать интересную книгу автора (Vachss Andrew)

|

Andrew Vachss

Two Trains Running

© 2005

1959 September 28 Monday 21:22

A candy-apple-red ’55 Chevy glided down the rain-slicked asphalt, an iridescent raft shooting blacktopped rapids. Behind the wheel was a man in his mid-twenties, with a wiry build and a narrow, triangular face. His elaborately sculptured haircut was flat on top, long on the sides and back, ending in carefully cultivated ducktails.

The Chevy’s headlights picked up an enormous black boulder, standing sentry in a grove of white birch. The driver pumped the brake pedal, then blipped the throttle as he flicked the gearshift into low. He gunned the engine, kicking out the rear end in a controlled slide through a tight S-curve. As soon as the road straightened, he eased off the gas and motored along sedately.

A quarter-mile later, the driver pulled up to what looked like a miniature cottage. A lantern-jawed man slowly rose from his seat on the one-man porch. He held a double-barreled shotgun in his right hand like an accountant holding a pencil.

“It’s me, Seth,” the driver said, out his side window.

“I knew that a few minutes ago, Harley,” the man with the shotgun replied. “Heard those damn glasspacks of yours a mile away.”

“Come on, Seth. I backed off as soon as I made the turn,” the driver said.

“You’re getting way too old for that kid stuff,” the man said reproachfully. He stepped closer to the Chevy. The driver reached up and flicked on the overhead light. The man with the shotgun glanced into the back seat, then shifted his stance slightly to scan the floor.

“Let’s have a look out back,” he said.

The driver killed his engine, took the keys from the ignition, and reached for the door handle.

“I’ll do it,” the man with the shotgun said. “You just sit there, be comfortable, okay?”

“Are you serious?” the driver said.

“You been here enough times, Harley.”

“Exactly,” the driver said, with just a hint of resentment. “So what’s with all the-?”

“Ain’t my rules.”

“Yeah, I know,” the driver said, sourly. “Let’s go, okay? The boss said nine-thirty, and it’s getting close to-”

“Next time, come earlier,” the man with the shotgun said, taking the keys.

He walked behind the Chevy and opened the trunk with his left hand, leveling the shotgun to cover the interior. He pulled a flashlight from his belt and directed its beam until he was satisfied. Finally, he closed the trunk gently, walked back to the driver’s window, and handed over the keys.

“See you later, Harley,” he said.

1959 September 28 Monday 21:29

The darkened house was a featureless stone monolith, the color of cigar ash. Harley ignored the horseshoe-shaped brick driveway that led to the front door; he drove carefully past the big house, his engine just past idle, until he came to a paved area clogged with cars. He slid the Chevy into a generous space between a refrigerator-white Ford pickup and a gleaming black ’56 Cadillac Coupe de Ville, and climbed out, not bothering to lock his car.

A short walk brought him to a freestanding single-story building. Its wooden sides had been weathered down to colorlessness, but the roof and windows looked newly installed.

As he approached, Harley saw his reflection in the mirrored finish of a small window set at eye level. Before he could knock, the door was opened by a short, bull-necked man wearing a threadbare gray flannel suit. The man’s perfectly rounded skull was covered by a thick mat of light-brown hair, roughly trimmed to a uniform length. His facial features were rubbery; his mouth was loose and slack.

“It’s me, Luther,” Harley said.

The short man nodded deliberately, as if agreeing with a complex proposition. His slightly protuberant eyes were as smooth and hard as brown marbles, reflecting the moonlight over Harley’s shoulders. Wordlessly, he tilted his head to the left.

Harley stepped past the slack-mouthed man into what looked like a modern two-car garage. A charcoal-gray Lincoln sedan was poised on the concrete slab, its nose pointing toward a wide, accordion-pattern metal door. Conscious of the other man somewhere behind him, Harley opened a door in the back wall, and followed a passageway to his left.

He paused at the threshold of a large, low-ceilinged, windowless room. One wall was lined with file cabinets, another with bookshelves. Various chairs and a pair of small couches were scattered about, all upholstered in the same dark-brown leather. Most of them were already taken. A few of the seated men glanced expressionlessly at the new arrival, the youngest man in the room.

The far end of the room was dominated by a lengthy slab of butcher block, laid across four sawhorses to form a desk. Behind it sat a massive man in a wheelchair, like a stone idol on a gleaming steel-and-chrome display stand. He had a large, squarish head, with wavy light-brown hair, combed straight back without a part, going white at the temples. His ears were small, flat against his skull, without lobes. Heavy cheekbones separated a pair of iron-colored eyes from thin lips; his nose was long and narrow; a dark mole dotted the right side of his jaw. The man was dressed in a banker’s-gray suit, a starched white shirt, and a midnight-blue silk tie with faint flecks of gold that occasionally caught the light. On the ring finger of his right hand was a blue star sapphire, set in platinum.

The man glanced at his left wrist, where a large-faced watch on a white-gold band peeked out from under a French cuff, then looked up at the driver of the Chevy.

“I was held up at the gate,” Harley said. “Seth took about half a day to…”

Nobody said anything.

Harley took a chair, and followed their example.

1959 September 28 Monday 21:39

“Procter!” a sandpaper voice blasted through the half-empty news-room.

All eyes turned toward a broad-shouldered man hunched over a typewriter. “What’s up, Chief?” he shouted back, without breaking his hunt-and-peck rhythm, eyes never leaving the keyboard.

“Get the hell in here!”

The broad-shouldered man kept on typing.

A pair of night-shift reporters at adjoining desks exchanged looks. One scrawled “2” on a piece of paper and held it up; the other crossed his two forefingers to make a “plus” sign. Each man reached for his wallet without looking, eyes focused on four large clocks on the far wall, marked, from left to right: Los Angeles, Denver, Chicago, and New York.

In perfect rhythm honed by long practice, a dollar bill was simultaneously slapped down on each man’s desk.

The second hands of the clocks swept on. One full revolution, then another. Two minutes and seventeen seconds had elapsed when…

“Procter, goddamn it!” rattled the windows.

The reporter who had made the “plus” sign plucked the dollar from the other’s desk as Procter slowly got to his feet. His hair was as black as printer’s ink; raptor’s eyes sat deeply on either side of a slightly hawked nose. Wearing a blue shirt with the cuffs rolled above thick wrists, and a dark-red tie loosened at the throat, he stalked through the newsroom holding several sheets of typescript in his right hand like a cop carrying a nightstick.

Procter ambled into a corner office formed from two pebbled-glassed walls. Behind a cigarette-scarred, paper-covered desk sat a doughy man wearing half-glasses on the bridge of a bulbous nose. His bald scalp was fringed with thick mouse-brown hair.

“Chief?” Procter said innocently.

“How many goddamn times have I told you not to call me that?” the doughy man snapped, his scalp reddening. “You’ve got a lot of choices in that department, Jimmy. ‘Mr. Langley’ will do. So will ‘Augie,’ you like that better. Save that ‘Chief’ stuff for your next editor.”

“So I’m fired?” Procter said, his voice not so much empty as without inflection of any kind.

“I didn’t say that!” the doughy man bellowed. “You know damn well what I meant. This isn’t one of those big-city sheets you’re used to working for. We do things differently around here.”

“I’ve been around here all my life,” Procter said, mildly. “Born and raised.”

“You like playing word games, maybe you want to take over the crossword. You haven’t been around this newspaper all your life. You came home, that’s what happened.”

“Came home after being fired, you mean.”

“I say what I mean, Jimmy. You’re a great newshound, but this is your fourth paper in, what, seven years? We both know you wouldn’t be working for the Compass if there was still a place for you with one of the big-city tabs.”

“I-”

“And we both know, soon as a job on a real paper opens up again, you’ll be on the next bus out of here.”

“I can do what I do anywhere.”

“Is that right? For such a smart guy, you do some pretty stupid things. What happened up in Chi-Town, anyway?”

“The editor spiked too many of my stories,” Procter said, in the bored tone of a man retelling a very old story.

“So you went behind his back and peddled your stuff to that Communist rag?”

“That exposé never saw a blue pencil, Chief. They printed it just like I wrote it.”

“Yeah, I guess they did,” the doughy man said, fingering his suspenders. “And I guess you know, that’s never going to happen here.”

“I’ve been here almost three years. You think I haven’t learned that much?”

“From this last piece of copy you turned in, I’m not so sure. Your job is to cover crime, Jimmy. Crime, not politics.”

“In Locke City-”

“Don’t even say it,” the editor warned, holding up one finger. “Just stick to robberies and rapes, okay? Shootings, stompings, and stabbings, that’s your beat. Leave the corruption stories for reporters in the movies.”

1959 September 28 Monday 21:52

“You sure he’s the guy we need for this?” a thin man with a sharply receding hairline and long, yellowing teeth asked.

“Red Schoolfield says he is,” replied the man in the wheelchair.

“Yeah, but that’s Detroit. We’re just a-”

“You ever been to Detroit, Udell?” the man in the wheelchair asked. He waited a three-second beat, then said: “Okay, then, how about Cleveland? You ever been there, either?”

“I was there one time,” the thin man said, his voice wavering between resentful and defensive.

“Good. Now, that’s a big city, too, am I right?”

“It is, Mr. Beaumont. They got buildings there you wouldn’t-”

“We’re not arguing,” said the man in the wheelchair. “In fact, you’re right-Cleveland is a big city.” He shifted his position slightly, so that his glance took in the entire room. “But here’s the thing, boys. Detroit and Cleveland, they’ve got one thing in common. You know what that is?”

“A lot of niggers?” a jug-eared man sitting in the far corner ventured, grinning.

“Yeah, Faron,” Beaumont acknowledged. “But you know what else they’ve got? They’ve got a whole ton of folks just like us. White people.”

“That don’t make them like us,” Harley ventured. He twirled one of his ducktails, a nervous habit.

“Now you’re using your brain, Harley,” Beaumont said, approvingly. “Being white’s just a color. Doesn’t make us like them, or them like us. There’s things inside color. Even the coloreds themselves see it that way. Look who they pick for their preachers and their politicians. It’s always the light-skinned ones, with that processed hair. The ones that got white in them, you don’t see them mixing much with the ones look like they just got off the boat from Africa.

“And it’s the same with us. With white people. Inside that color, we got all these groups. Like… tribes, all right? You’ve got the Italians, you’ve got the Irish, you’ve got the Jews, you’ve got the-”

“Jews?” a man with long sideburns, wearing a leather aviator’s jacket, piped up, somewhere between a question and a sneer.

“Sure, Jews,” Beaumont said. “What did you think, Roland? They weren’t in our business?”

“I thought they was all… I mean, maybe in the business, but not at our end. Not like the stuff we-”

“You should read a book once in a while,” Beaumont said, “it wouldn’t hurt you. Wouldn’t hurt you to pay attention to what goes on in the world, either. You go back far enough-and, trust me, it’s not that damn far-you find Jews started the same way we did. With this,” he said, knotting a fist and holding it up to the faint light from the desk lamp, like a jeweler checking a gem for flaws.

“I never heard of a kike with the balls for muscle work,” Udell said.

“Udell,” Beaumont sighed, “you never heard of a lot of things.”

“What’s this got to do with Detroit and Cleveland, Roy?” asked an older, broad-faced man with eyes so heavily flesh-pouched that it was impossible to tell their color.

“That’s getting to it, Sammy!” Beaumont said, nodding his head for emphasis. “Look,” he said, slowly turning his massive head like a gun turret to cover each man facing him, “there’s neighborhoods in both those cities where there’s mostly people like us, understand?”

“Hillbillies?” a tall redhead with long sideburns said, chuckling. He was wearing an Eisenhower jacket over a thick sweater, despite the warmth of the room.

“You know I don’t like that word, Lymon,” the boss said. He didn’t raise his voice, but his words carried easily, seeming to echo off the walls. “We’re not hillbillies, we’re mountain men. And this town, it’s our mountain, understand?”

There was a general hum of agreement from the assembled men, but no one spoke.

“People like us, we’re clannish,” Beaumont continued. “We want to live among our own kind, even when we’re feuding amongst ourselves. You go to any city, even as big a one as Chicago, you’ll find a section where our people live. That’s no accident. Those pieces of the city, it’s just like this town here. You understand what I’m telling you? Red Schoolfield, he’s in a bigger city than this one, sure. But only a little piece of it belongs to him. What we got here, it’s all ours. Not just some slice-the whole thing.”

The man in the wheelchair paused, individually eye-contacting each man in the room before he went on:

“You all know how it works. Remember when we were kids? You got yourself a candy bar, what happened? Some guys, they’d want a little piece for themselves, right? And if they were your pals, well, you were supposed to cut them in. But there was always this one guy, what he wanted was the whole thing. Am I right?”

Nods from around the room. The broad-faced man added a grunt of assent.

“Now, if this guy is bigger than you, or tougher, what do you do then? Well, you got choices. You can stand and fight, make him take it, but all that gets you is a beating.

“So the thing you do, if you’re like us, you give up the candy, and you wait for your chance. Then you ambush the guy, maybe bust up his head with a brick. And next time he sees you with candy, well, he keeps walking. Or, even better, you get a few of your pals-the same guys you would share with-and you mob the motherfucker, pound him so bad he don’t want any more, ever.

“You can’t change a bully. The best you can ever do is make him work, make it cost him something. They don’t like that, so they go and pick on someone else. That’s where all this started, boys, what we have now.

“And the first rule is, always, you make sure you control your own territory. Maybe it’s only a tiny little piece, but it’s yours. Now, once you got land, a piece of ground that’s really yours, you can’t just let it sit there, you got to do something with it, am I right?”

More nods.

“Sure, I’m right! And I’m not talking about naming it after yourself, the way Old Man Locke did back when he opened the first mill, before any of us were born. I’m talking about making your living from it. Land is money. You can farm it, or you can brew mash on it, or you can open a little roadhouse, or… well, it doesn’t really matter. What matters is that you get something going.”

Beaumont’s iron eyes swept the room, a seismograph, searching for the slightest tremor of inattention. Satisfied, he went on:

“You can see it happening, everywhere you look. The Irish, the Italians, they can run a whole city, but not by themselves. When they want to do business with people outside their tribe-and you know, they have to do that-they need… branch managers, I guess you’d call them. And, sooner or later, those managers, they see how things work, how much money there is to be made, they want to go into the business for themselves.

“That’s what we did. That’s how we got started here. We built up a beautiful thing for ourselves. We got the gambling, we got the girls-not just the houses, the strip joints too-we got the jukeboxes, we got the punch cards, we got the liquor, we got money out on the street, working for us… And when dope hits this area hard-the way it has up in the big cities-we’ll have that, too.

“But, remember, every time you got that candy, here comes some big guy who wants it all for himself. You understand what I’m saying?”

“Those wop bastards don’t have a chance,” the broad-faced man said, with the calm assurance of a man stating a known fact.

“It depends on what they want to put into it, Sammy,” the man in the wheelchair said. “They know we’ve got the cops and the judges, but they also know those people aren’t with us-they’re just whores, charging us for every trick. When this jumps off, they’ll stand on the sidelines, and climb into bed with the winners.”

Beaumont looked around the room, using his eyes to lock and hold each man individually before he continued:

“Now, you know, they’ve already been around, the Italians. Sat down with me. Very nice, polite. They just want a little taste, is what they say. But it would never stop there. When they come for us, they’re going to come hard.”

“You really think one guy’s going to make that much of a difference?” Lymon asked.

“You mean, do I think we need him?” Beaumont said. “Hell, no. What Sammy said is the truth. The outcome’s not in doubt. But being a good general isn’t just about winning wars; it’s about keeping your men safe, too. And if this guy’s half as good as I’ve been told, he’ll get it over with quick.”

1959 September 28 Monday 22:09

A battleship-gray ’56 Packard sedan purred down the interstate, past the exit marked LOCKE CITY. A few miles later, the driver pulled into a service area. He drove to the pumps, glanced at the dash, noted the gas gauge read just below the halfway mark, and shut off the ignition.

“Fill it up with high-test, and check the oil and water, please,” he told the young man wearing a blue cap with a red flying-horse emblem who came to his rolled-down window.

As the pump jockey went to work, the driver walked over toward the restrooms, hands swinging free at his sides. As he turned the corner of the building, he encountered a pay phone. The man slotted a coin, dialed a number, and waited, his back to the wall.

“I was told you’d be expecting a call. About your garage,” he said into the receiver. His voice was flat, using neither volume nor inflection to communicate.

He listened for a few seconds, then said, “I can find it. Inside of an hour, all right?”

The man listened again, then hung up.

“Took almost twenty gallons,” the pump jockey said when he returned. “Man, you were empty. Oil’s okay, though.”

The man paid his bill, got behind the wheel. He noted approvingly that the pump jockey had cleaned his windshield.

1959 September 28 Monday 22:30

At the next exit, the driver circled back and re-entered the highway, heading back the way he had come. As he turned off at the Locke City sign, he pushed a button set into the gauge cluster. The four-digit row of numbers reset itself to 0000. A trip odometer began to click off the miles, the rightmost numerals, in red, indicating tenths.

From an inside pocket, the driver took a hand-drawn map, which he taped to the padded dashboard. He followed County Road 44, keeping the big car at a subdued pace, watching the odometer. When the mileage reading hit 013.4, the driver slowed slightly, his eyes another pair of headlights.

The dirt road was unmarked, barely wide enough for two cars. The driver turned in cautiously, pulled as far over to the side as possible, and extinguished his headlights. He rolled down his window, plucked a nearly full pack of Lucky Strikes from the seat next to him, and turned it around in his right hand, over and over, breathing shallowly through his nose.

Several minutes later, the driver tossed the pack of cigarettes back onto the front seat. With his left hand, he thumbed the fender-mounted bullet spotlight into life.

The big car crawled forward cautiously as the dirt road narrowed, became rougher. The spotlight picked up the remnants of a tar-paper shack. It had no door, no glass in either of its two windows, half its roof, and only three of its walls.

The driver steered into the clearing behind the shack. He stopped the car and stepped out, leaving the door open and the engine running. He circled the car, opening each of the other doors in turn. The overhead interior light was intense, illuminating the seats and floor of the Packard as brightly as if it were in a showroom. He then unlocked the trunk, activating still another light.

The driver stepped away from his car and lit a cigarette, holding it in his left hand. His right dangled at his side, empty. He stood utterly still. Not tense, motionless.

The night-sounds merged with the barely discernible throb of the Packard’s engine, its power muted by a set of highly restrictive mufflers.

The driver raised one foot, ground out his cigarette on the sole of his shoe, and deposited the butt in the pocket of his dark-blue sport coat.

“Whisper said you was one careful motherfucker.” A voice came out of the darkness, seemingly pulling a man along in its wake. A barrel-shaped black man wearing denim overalls and an egg-yolk-yellow T-shirt emerged: He was holding a long-barreled revolver in his left hand, pointed at the driver’s midsection.

“Careful for me; careful for you,” the driver said, nothing in his voice but the words themselves.

“You right about that,” the black man said, moving closer, “if Whisper was right about you.”

The driver shrugged, to show that decision was out of his hands.

“You know how the garage works?” the black man asked.

“I leave my car with you. You give me another one to use. When I’m done, I call you, and we trade back.”

“Uh-huh. And Whisper, he told you, it costs a grand, right?”

“Five hundred is what he said.”

“Price of everything’s going up,” the black man said. “That’s the way it is, everywhere you go.”

“Whisper said that, too.”

“Prices going up?”

“No. That you’d try and hold me up for more. He under-estimated you-he was guessing an extra C-note.”

A flash of white scythed across the black man’s face. It might have been a smile. “You know what I mean, I say I been listening to the drums?”

“Grapevine.”

“Right. People know you coming, man. They don’t know your name, don’t know your face. And I guess you don’t want them to know your car, either.”

The driver shrugged again.

“Sure,” the black man said. “So what that means is, I got extra expenses.”

The driver watched, silently.

“You ain’t holding up your end,” the black man said, the thin slash of white back in his mouth.

“The money’s-”

“Of the conversation, man. This is what men do, they got a dispute. They talk about it, right?”

“We don’t have a dispute.”

“Sure, we do. I don’t mean we enemies or nothing like that. Just trying to get you… involved, see?”

“In what?”

“In my problem, man. What I been telling you.”

“Your ‘extra expenses.’ ”

“Now you paying attention. I don’t know you. Don’t want to know you. But I know what you here for. So I got to figure at least some possibility I may never get that phone call from you, understand where I’m going?”

“That you won’t get your car back.”

“That’s right! Now you getting with the program. I got a real nice… rental for you. You can drive a stick, right?”

“Yes,” the driver said. He took out his pack of cigarettes, held it toward the black man.

“No thanks, man. Appreciate it, though. Anyway, what I got for you is a sweet little ’49 Ford. But it’s not running no flathead-got a ’54 Lincoln mill with a lot of work into it. All heavy-duty: brakes, shocks, clutch, everything. Floor shift, Zephyr gears. Some wild-ass kid built it for drag racing. It don’t have a lot of top end, but it’ll walk away from any cop car in this town. Get you good and gone, you need to.”

“Sounds fine.”

“She is fine, man. What I’m telling you, she don’t come back, I’m out a lot of coin, see what I’m saying?”

“No. No, I don’t. I see you coming out ahead. My car’s worth a lot more than some kid’s hotrod.”

“Yours is newer, sure. But that don’t-”

“Mine’s running a punched-out Caribbean engine,” the driver interrupted. “Dual quads, headers, triple-core radiator, cutouts for the pipes. The whole chassis has been redone, and it’s got a belly pan, too. You could drive it through a cornfield at thirty and it wouldn’t get stuck. Got a second gas tank in the trunk: extra twenty-five gallons. Steel plate behind the back seat-”

“Damn!”

“There’s more. Go look for yourself, you don’t believe me. Cost you seven, eight grand, minimum, to build anything like it.”

The black man’s eyes narrowed. The pistol in his hand moved slightly. “Must make you worried, then. Leaving a valuable ride like that with a stranger. I mean, what if you called and I never came?”

“I’m not worried,” the driver said. “Whisper vouched for you.”

“Man can always be wrong.”

“Whisper told you about me,” the driver said. It wasn’t a question.

The black man nodded.

“Well, he wasn’t wrong about that,” the driver said.

1959 September 28 Monday 23:39

Only Sammy, Lymon, and Harley remained behind after the others had been dismissed, their chairs drawn up close to Beaumont’s desk. The men spoke in low, but not guarded, tones.

“We already lost one man,” Beaumont said. “Hacker never came back with the casino collection. It’s been over three weeks, and nobody’s heard from him.”

“That was a lot of money,” the broad-faced man said.

“Meaning what, Sammy?” Beaumont asked, swiveling his imposing head in the speaker’s direction.

“Everybody knows Hacker’s route,” Sammy said, unruffled. “It’s no secret. All our collectors work alone. We never have anyone riding shotgun. Everybody knows that, too.”

“You’re saying-what?-we don’t have any proof that it was Dioguardi?”

“I’m saying, it could have been Dioguardi, sending a message, sure,” Sammy said. “But it could have been a hijacker, too, Roy. A freelancer, I mean. We got no shortage of those coming through here. Most of them, they’ve got enough sense to come to our town to spend the money they made off their jobs, not to pull one… but every deck always has at least one joker in it.”

“Can’t say it wasn’t,” Beaumont mused. “But Hacker was always a ready man. He wouldn’t go easy… not unless he went willingly. And, you know, if you’re going to take down something big, like an armored car, say, the best way is to have an inside man.”

“Hacker wouldn’t steal from us,” the redheaded man put in, sure-voiced.

“I don’t think so, either, Lymon,” Beaumont agreed. “It was a good piece of change, all right, but not enough to live on for the rest of your life, if you had to stay hidden. When the cops came out here, they said nothing in his house had been touched. There’s things a man wouldn’t leave behind if he had time to plan his run.”

“Hacker would know that, too,” Sammy said, cautiously.

“He would,” Beaumont said, nodding his head. “But you know what else the cops found when they went to his place? They found that hound of his, Ranger. Dog didn’t even have food laid out for him.”

“That does it for me,” Sammy said, in a tone of finality. “Hacker loved that old dog. He expected to come home that night. Yeah.”

“So what’s our first-?” Harley asked, as a woman entered the room from the door behind Beaumont. She was of medium height, but looked shorter because of her stocky frame-an impression enhanced by her low-heeled shoes and boxy beige jacket worn over a plain white blouse. Her hair was the color of tarnished brass, worn short, with moderate bangs over her high forehead. She had Beaumont’s iron eyes, but long lashes and artfully arched eyebrows banked their fire.

At her entrance, the assembled men all rose to their feet and started for the exit.

“Lymon, you mind hanging around a few minutes?” Beaumont said.

By way of response, Lymon sat down.

1959 September 28 Monday 23:52

As if by prior assent, the two men walked across the clearing to the waiting Packard. The driver reached into the trunk, removed a pair of suitcases, stood them on the ground.

“Watch this,” he said, quietly. He lifted the heavy pad of felt that lined the floor of the trunk, revealing a flush-mounted keyhole.

“Now watch me,” the driver said, emphasizing the last word. He reached-slowly-toward his belt, carefully removed the tongue of the belt buckle, extracted a metal rod with a single notch at one end, and held it up for the other man’s inspection. He inserted the rod into the keyhole and turned his wrist-a shallow compartment was revealed. Filling the compartment edge-to-edge was a black, hard-shelled attaché case.

The driver removed the case, added it to the luggage on the ground, closed the compartment, pulled the felt back into place, and closed the trunk.

“Why you showing me all this?” the black man asked, more curious than hostile.

“I didn’t want anyone tearing up the car looking for… whatever they might find. So I thought I’d show you where the tricks were myself.”

“Pretty slick. But what’s the story with that key in your belt, man? Strange place to keep it.”

“It doesn’t just open the compartment in the trunk. It’s a speed key… for handcuffs, understand?”

“Yeah,” the black man said, shaking his head slowly. “But when they bring you down, first thing, they take away your belt and your shoelaces.”

“That’s after they get you to the jail,” the driver said. “Sometimes, their plans don’t work out.”

The black man stepped back a pace, but kept his pistol leveled.

“Look, man. Like I said, it was on the drums. Killer on the road, coming to town. Everybody knows there’s a gang war coming. That’s ofay business, got nothing to do with me, one side wants to bring in some outside talent. But if you kill a cop, even one of those blue-coated thieves that works for this town, that’s gonna bring heat like an oil-field fire. That happens, you call the number you got for me, nobody’s gonna answer. This big car of yours, it’s gonna get butchered like a hog, man. Cut up so small its own mother wouldn’t know it.”

The driver looked at the black man’s chest, expressionless.

“Whisper didn’t say nothing about dusting no po-leece,” the black man said, his voice feathering around the edges.

“Whisper didn’t say anything,” the driver said. “All he did was make a deal. And here I am, holding up my end of it.”

“I-”

“If you don’t want to go through with it, now’s the time to say so.”

“I didn’t say nothing about-”

“You take the deal, you take it the way it was laid out,” the driver cut him off. “What I do, that’s not your business. What you do, that’s not mine. But if I call that number and there’s no answer, there’s another number I can call, understand?”

“Whisper ain’t gonna side with no gray boy against his own-”

“You took this deal, and you don’t know Whisper?”

“I know him,” the black man said, capillaries of resentment bulging on the surface of his voice.

“You never met him,” the driver said, confidently. “You know him the same way everyone else in the game does, by reputation. That’s all he’s got, his reputation. Whisper vouched for you. You come up wrong, nobody’s going to want to deal with him anymore. Not until he fixes the problem. Sets an example.”

“You saying Whisper would do something to me?”

“Get it done, yeah.”

“That supposed to scare me?”

“What it’s supposed to do, it’s supposed to get you to make a phone call. Ask him yourself. I’ll wait right here while you go and do it. You call Whisper. After you speak to him, you still think you can go back on our deal no matter what happens, I’ll just take my car and go. No hard feelings.”

The black man’s face tightened. “You must think I’m a stone fucking chump, Wonder Bread,” he said. “I tell Whisper I’m even thinking about not holding up my end, that’s the last business I ever get from him.”

“Up to you,” the driver said, making an “It’s all the same to me” gesture. “One of us is going to be driving my car out of here. Who that is, that’s up to you.”

1959 September 29 Tuesday 00:04

“Every time that sister of his comes into the room, the show’s over, huh, Sammy?” Harley said to the broad-faced man as they were walking toward their cars in the lot.

“Roy knows what he’s doing,” the broad-faced man said, a faint thread of warning in the blend of his voice.

“Yeah? I don’t see what Cynthia’s got to do with anything, myself. The way she acts sometimes, it’s like she’s the boss, not him.”

Sammy kept walking, silent.

“You don’t think it’s a little strange, Sammy?” Harley persisted.

“What I think is, nobody ever got themselves in trouble minding their own business.”

“I was just saying-”

“Harley, you’re a comer. Everybody knows that. The man himself has his eye on you.”

“So?”

“So listen to an older hand for a minute, son. There’s a lot more to Royal Beaumont than a big set of balls.”

“You saying-what?-people don’t think I got the brains to run my own-?”

“I’m not saying that, Harley… although, when you pull kid stuff like coming late to meetings, you make folks wonder. Look, I know you’ve got a head on your shoulders. But having something’s not the same as using it, you follow me?”

“Sammy…”

“I came up with Roy,” Sammy said. “We go back. All the way back. You know what the smartest thing you can say about his sister is?”

“Nothing?”

Sammy reached over and squeezed the younger man’s shoulder. “See how smart you can be when you work at it?” he said.

1959 September 29 Tuesday 00:12

“There’s three toggle switches right under the dash,” the driver said, pointing with his forefinger. “Just slip your hand under there, you’ll feel them.”

The black man deliberately turned his back and reached under the dash, tacitly acknowledging that the pistol he had been holding hadn’t been the protection he first thought it was.

“First one kills all the interior lights; in the trunk, too,” the driver said. “You push it forward, they won’t go on, no matter what’s opened. The second one-the one in the middle-that’s the ignition kill switch. Push it forward, and you can’t start the car, even with the key. The last one is the muffler cutouts. Okay?”

“I got it,” the black man said, stepping back out of the car.

“Then let’s go get that Ford of yours.”

“I don’t think so, man. You just wait here, we’ll bring it to you. An hour, no more. Man like you, I’ll bet you an ace at killing time.”

“You’re a funny guy,” the driver said.

1959 September 29 Tuesday 00:21

“You’re really sure we need an outsider in on this?” the tall, red-haired man asked. He had moved his chair so that it was alongside Beaumont’s desk, canting his lean body at an angle to create a zone of privacy.

“An outsider’s exactly what we need, Lymon,” the man in the wheelchair answered. “You know how men like Dioguardi work. Before they make a move, they always count the house. They think they know every card we’re holding. This man, he’s going to be our sleeve ace.”

“Where do you find someone like him, anyway?” Lymon asked. “The mobbed-up guys, they’ve got a whole network. They want a job done in, I don’t know, Chicago, the boss there, he makes a call, and the boss in… Miami, maybe, sends him someone to do it. But that’s not us. I mean, we know people, sure. But they’re independents, like we are. They’re not with us.”

“That’s true.”

“You trust Red Schoolfield enough to use one of his guys? I heard that he wasn’t going to be able to hold out much longer himself. Maybe he already made his deal.”

Cynthia walked over to the liquor cabinet, opened two small, unlabeled, brown glass bottles, and carefully shook a pill from each. She expertly tonged three ice cubes into a square-cut tumbler, added water from a carafe, and brought it over to Beaumont. He plucked the pills from her open palm, put them in his mouth, and emptied the tumbler.

“More?” she asked.

“Please.”

Without another word, Cynthia fetched the carafe and refilled Beaumont’s glass. She returned the carafe to the liquor cabinet unhurriedly, clearly intending to remain in the room.

A silver cigarette box sat on Beaumont’s desk. He opened it, turned it in Lymon’s direction. Lymon shook his head “no,” completing the ritual. Beaumont took a cigarette from the case, fired it with a table lighter. He adjusted his position in his wheelchair, blew a perfect smoke ring at the ceiling.

“This guy-Dett is what he calls himself, Walker Dett-he didn’t come from Red. I knew Red had used him on a job. All’s I did, I gave Red a call, asked him how it had worked out. Like a reference.”

“So where did you find him?” Lymon persisted.

“You know Nadine’s roadhouse?”

“Everybody knows Nadine. She-”

“This isn’t about her,” Beaumont said, the “Pay attention!” implicit in his tone. “You go out there, to her joint, once in a while?”

“Not really. Only when-”

“When they’ve got certain bands playing, am I right?”

“Yep,” Lymon said, enthusiasm rising in his voice. “They get some real corkers out there, sometimes.”

“Like Junior Joe Clanton?”

“That’s one for sure!”

“Absolutely,” Beaumont agreed. “Now, Junior Joe, he’s no Hank Williams. But who is? What I mean is, Junior Joe was never on the Opry. And you’re never going to hear one of his songs on the radio. But when word gets out he’s coming to town, you know there’ll be a full house somewhere that night.”

“Yeah. I don’t understand why he never got… big. That boy’s got a voice like… well, like nobody else.”

“Maybe that’s the way he wants it,” Beaumont said. “All men pretty much want the same things-the same kind of things, anyway-but different men, they go after it different ways. I know what Nadine has to shell out to get him to work her place. If he does that good everywhere he plays, Junior Joe’s making more money a year than some of the big stars.”

“And he gets paid in cash, right?”

“That could be part of it,” Beaumont conceded. “But I don’t think it’s the whole story. Maybe… You remember Debbie Jean Watson? Hiram Watson’s daughter? That girl won every beauty con-test in the whole damn state. Far as a lot of folks were concerned, she made Elizabeth Taylor look like a librarian. Remember what happened to her?”

“She went out to Hollywood…”

“And never came back. You know why? Not because she couldn’t act. Hell, there’s all kinds of movies where the girls don’t have to do anything but look good. You’d think she could at least get some of that kind of work. Face like hers, body that could wake the dead, she walks in a room, she owns every man in it. But the thing is, Lymon, the camera didn’t see her the way men do in real life. The way I understand it, those movie cameras, they don’t work the same as a man’s eyes do. You need a special look to make them love you. And Debbie Jean, she didn’t have it.”

“So maybe that’s Junior Joe, what you’re saying? He’s got the voice for honky-tonks, but not for records?”

“I don’t know,” Beaumont said. “All I’m saying, there’s reasons for everything.”

“What’s this got to do with-?”

“This Walker Dett, he’s kind of like Junior Joe. A honky-tonk man, moving from town to town. You want him, you call this number. They give you another number-that one’s always changing-and you just leave a message. Somebody calls you back-maybe somebody calls you back-and you make a deal. Like booking an act, see?”

“So how do people even know about him?”

“Same way they do about Junior Joe. Word of mouth. Which is why I asked Red Schoolfield, was he as good as people say? And Red, he said he was.”

“It seems like a lot of trouble just to hire a gun,” Lymon said. “There’s always been plenty of freelance firepower around. Even more, since Korea ended.”

“Plenty of horses get foaled every year, too,” Beaumont said. “But how many of them end up in the Kentucky Derby? This guy, he’s in a different class from anyone we could find around here.”

“But what if the outfit guys really aren’t planning-?”

“Don’t kid yourself,” Beaumont said, scornfully. “You think they’re just talk? They already made it clear-they’re going to get a taste of what we got. And once they get that taste, you know what happens next.

“Look, Lymon, they’re all businessmen. Just like us. They want our action. What we have to do is make it so costly for them that it’s not worth it. And this guy I’m bringing in, he’s just the man for that.”

“Beau…?” his sister said.

“All right, Cyn. I know.” Turning to Lymon, he said, “Doc says, I don’t get some sleep after I take those damn pills, they’re not going to do the job.”

As he got up to leave, Lymon asked, “Whatever happened to her?”

“Who?”

“Debbie Jean Watson. Like you said, she never came home.”

“Oh, yeah. Well, it seems there’s all different kinds of cameras. Movie cameras, she couldn’t do a thing with them. But she was good enough for the other kind.”

1959 September 29 Tuesday 01:19

The big house was quiet. The man in the wheelchair rolled himself down the hall to a master-bedroom suite, where flames in a stone fireplace cuddled rough-hewn logs. A triple-sized tub in the attached bathroom was surrounded by handrails. He backed his chair against the wall, and sat in darkness until his sister lit a thick red candle in the opposite corner.

“I suppose you’d like one of your awful cigars,” she said.

“Sure would.”

“You don’t have to always have one before-”

“There’s a lot of things I do have to do, Cyn. Some of them, I wish I didn’t. I get the chance, do something I like to do, doesn’t matter that I don’t have to do it, right?”

“You could just try something else, for once.”

“Why?”

“Because you might like it better.”

“I couldn’t like it any more than I already do.”

“You might, Beau. You used to…”

“That was when I still could-”

“Try one of these, instead,” she said, walking over to his wheelchair, a red-and-gold box in her hand. “Special cigarettes. From Turkey.”

“I… ah, what the hell, Cyn. You know I always give you what you want.”

He reached for the box of cigarettes. Cynthia took a step back. “After,” she said, caressingly. Then she knelt before the wheelchair.

1959 September 29 Tuesday 02:04

“These are good,” Beaumont said, exhaling a powerful jet of smoke.

“See?”

“Yeah. But they won’t last as long as a good-”

“So you’ll have another,” the woman said. “If you want one.”

“I just might,” Beaumont said. “Now, tell me, what’s your read on the meet we just had?”

“Red Schoolfield is a moron,” his sister said.

“I know that, Cyn. You think I didn’t get word from other places on this guy I’m bringing in? Red’s the only name the boys need to hear, that’s all.”

“Lymon’s shaky,” she said. “But that’s nothing new-he’s been weak for years. Of all the men, he’s the least likely to go the distance, should it ever come to that.”

“Yeah,” the man in the wheelchair agreed. “And I think we could be walking close to that line now. That’s why I called him aside at the end. He’s been talking to the Irishers.”

“Roy! How could you know that?”

“I know,” he assured her.

“So this stranger, you’re really bringing him here for Lymon?”

“No. What I told the men he was for, that was the truth. We talked about this, Cyn. Dioguardi’s already putting some of our accounts in a cross. Look at the jukeboxes. Every joint in the county knows they have to use the machines we send them. Now Dioguardi’s outfit’s coming around, telling them they have to use theirs. And if they don’t want to do that, they have to pay a tax to use ours. The squeeze is too tight.

“It’s our town,” the man in the wheelchair said, “so it’s our play. And that’s when this guy I’m bringing in earns his money.”

“What about Lymon?”

“I was thinking of Harley. That boy’s sharp. And he’s good with his accounts, too. But he’s never shown his stuff, not that way.”

“He’s awfully young, Beau. I don’t know…”

“Everyone who started with us, they’re my age now, Cyn. If we’re going to keep this going… after, we need a younger man. I know I’m right about Harley, he just needs more seasoning.”

“I can’t see men like Faron and Sammy-”

“-following a kid like Harley? It’s not them we have to worry about, honey. They’re old pros. And they’re not going to be working forever, either. It’s the next wave, men like Udell and Roland, that Harley’s got to win over. And all the smarts in the world won’t be enough for that-you know what he has to do.”

“Yes,” Cynthia said. “But… Oh, never mind that for now, Beau. When are we expecting this man you sent for?”

“Tomorrow, the next day, sometime soon. He’s on the road right now, heading this way. Soon as he checks into the Claremont, he’s going to call.”

1959 September 29 Tuesday 03:55

“Can’t sleep, Beau?”

“I don’t need much, Cyn. You know that.”

“Yes, but you need some. It’s very late. Do you want-?”

“No, thank you,” the man in the wheelchair said, almost formally. “I just… wanted to think some things through, I guess. You know how people tell you, when you got a problem, you should ‘sleep on it’? Well, that’s the coward’s way. The right way is, you grab on and wrestle with it.”

“You always were a great wrestler, Beau.”

“Used to be, honey. Used to be.”

“I don’t think there’s a man in this town who could take you at the table, right this minute,” Cynthia said, shaking her head as if to dispute any doubters.

“I guess I should be strong, all those exercises you used to make me do.”

“You had to do them, Beau. The doctors said… this would happen, someday.”

“You can say ‘wheelchair,’ Cyn. The word doesn’t scare me. Not anymore, anyway. When I was a kid, I hated those braces I had to wear. Now I wish I had them back.”

“Beau, we don’t have to… do any of this. We could go somewhere else. Florida, maybe. We have enough money…”

“How long you think all that money would last us, we did that? Most of what we have, it’s not hard cash, Cyn. It’s tied up, in all kinds of things. The money that keeps you safe is the money that keeps coming in. Like an electric fence-the minute you turn off the power, anyone can just walk right through it.” Beaumont looked at the glowing tip of his cigarette. “Power,” he said, quietly. “That’s what keeps us safe. And money, money coming in, that’s only a piece of it. The men, my men, the men who stand between me and everyone else, you think I could buy that with money?”

“Of course not. Even if you were down to your last penny, Luther would never-”

“Yeah, I know, honey. But Luther’s our own, like Sammy and Faron are. You can buy a man’s gun, but that doesn’t mean you bought his heart. Bodyguards, they’re nothing but bullet-catchers-and they know it. One day, you pay them to stand in front of you; another day, someone else could pay them to stand aside.

“You look at some of those countries in South America. Every time you turn around, they got a new guy in charge. You think, how could that happen when the boss, he’s got a whole army on his side? Easy. Somebody in that same army decides he wants to be the boss. You read between the lines, you can see it clear. The difference between a bodyguard and a hit man, it’s whose money he’s taking, that’s all.”

“Is that why Lymon-?”

“Lymon? No. He doesn’t have it in him to even think about taking over from me. He’s the kind of man who’s got to be with someone stronger. That’s why he’s always been with me. And that’s why he’s talking to the Irish guys, too. Hedging his bets.”

“But why would they trust someone like him? If he’d sell us out, why wouldn’t he-?”

“-do the same to them? He would. And they have to know it. Once a man betrays his own, no one else can ever trust him again. Lymon was a good man, once. But even back then, he never knew how to plan ahead.”

“Nobody can plan like you, Beau,” his sister said.

1959 September 29 Tuesday 11:53

“Welcome to the Claremont,” the desk clerk said, glancing down at where the guest had signed the register. “We have you in 809, Mr. Dett. That’s a corner room, deluxe, with shower and bath, for two weeks, is that correct?”

“Two weeks, that’s right,” the guest agreed.

“Let me get you some help with that luggage,” the clerk said, hitting a bell and hollering “Front!” simultaneously.

“Appreciate it,” Dett said.

“Would you like me to send a boy out to take care of your car, too, sir? We have parking around the back, complimentary for hotel guests.”

“No thanks,” Dett replied. “I didn’t drive. Came in on the plane from Cincinnati, then I grabbed a cab. I figured I’d rent a car while I’m in town. That’s the way I always do it.”

The desk clerk prided himself on being a superb judge of humanity, able to size up any new guest in minutes. He often regaled his mother with his Sherlockian deductions at the end of his shift. As he filled out the registration card, he covertly took stock.

The man on the other side of the counter was clean-shaven, the facial skin stretched tightly over sharp cheekbones. His dark-chestnut hair was cut almost military-short. His hands were well cared for, but two knuckles of his right hand were flattened, marked with white keloid starbursts. A simple steel watch with an expansion bracelet constituted his only jewelry. His dark-blue suit, although clearly well fitted, was what the clerk’s mother would have dismissed as “decent.” A gray felt fedora, a plain white shirt with a spread collar and button cuffs, and a black tie-a little wider than was currently fashionable-didn’t help with the diagnosis. Nor did the man’s luggage, an unmatched set of two suitcases, a Pullman and a smaller job, plus a generic attaché case.

A traveling salesman working the circuit would have made conversation about the weather, like a boxer sparring to keep in shape. A confidence man would be either flashier or more richly conservative in dress. A gambler would carry cash in the buttoned breast pocket of his shirt. A gunman would be wearing a shoulder holster. An itinerant preacher would have a Bible somewhere in sight. The clerk glanced down at the register, saw that Mr. Walker Dett had listed his business as “real estate,” whatever that meant.

Under other circumstances, the clerk would have asked a couple of questions-friendly questions, of course. But there was something about this man, some… stillness to him, that made the clerk nervously finger the single pearl anchored precisely in the center of his plum-colored necktie.

“Rufus will show you up to your room, sir,” the clerk said, as a handsome mahogany-colored man in his early thirties approached the front desk, dressed in a resplendent red bellhop’s uniform, with rows of gold braid across the chest and “Claremont” spelled in the same material on his round cap. “We hope you enjoy your stay with us. If there’s anything you need, just let us know.”

“Thanks,” said the guest. He picked up his attaché case, and pointed with his chin to the two suitcases on the floor. The bellhop hefted the two suitcases, said, “This way, sir,” and started toward the elevator.

In response to the bellhop’s ring, the elevator cage slowly descended. It was opened by an elderly man whose teakwood complexion was set off by a skullcap of tight gray curls. He was wearing a red blazer with the “Claremont” name and crest on the breast pocket.

“We need eight, Moses,” the bellhop told him. “The top floor,” he added, unnecessarily.

“Sure thing,” the elderly man said. “Welcome to the Claremont, suh,” he told the guest.

“Thank you,” Dett replied.

The cage came to a dead-level stop on the eighth floor, the operator working the lever so smoothly there was no sensation of movement.

“Very nice,” the guest said, touching the brim of his hat.

“Yes suh!” the operator said, flustered. He had been driving that elevator car for more than twenty years, and this was the first time anyone had ever taken note of his dextrous touch, much less complimented him on it.

The bellhop led the way down the hall. When he came to the last door on his left, he put down one of the suitcases and withdrew a key from his pants pocket in one fluid motion. He unlocked the door, pushed it open, stood aside for the guest to precede him, then picked up both suitcases and followed.

The bellhop opened the door to the bathroom, turned on the taps, opened the medicine cabinet. Then he walked officiously to the windows and drew back the curtains, clearly on a tour of inspection.

“This here’s one of our very best rooms,” he told the guest. “Over to the front side, it can get real noisy, with all the traffic in the street. Back here, it stays nice and quiet.”

“It’ll be fine,” the guest said, handing over a dollar.

The bellhop’s smile broadened. Most professional travelers generally thought a quarter was generous. The action men, the gamblers and the hustlers, they always went for halves. Only Hoosiers and honeymooners tipped dollars. Rufus, who knew an omen when he saw one, resolved to play 809 when the numbers runner came by that afternoon.

“If there’s anything you need, sir, anything at all, you just ask for Rufus. Whatever you might want, I get it for you.”

“This a dry town?” the guest asked.

“No, sir. Truth is, folks comes here, they want to get themselves a taste.”

“Appreciate your honesty,” the guest said, handing over a ten-dollar bill. “This’ll buy me a fifth of Four Roses, then?”

“With plenty to spare, sir,” the bellhop confirmed. “I’ll be right back.”

On his way over to the liquor store a block away from the hotel, the bellhop congratulated himself on not lying about the easy availability of liquor in Locke City-the guest had asked the question as if he already knew the answer. Whoever he is, Rufus thought, he ain’t no Hoosier.

The man who had signed the register as Walker Dett tossed his two suitcases onto the double bed, gave the room a thirty-second sweep with his eyes, then picked up his attaché case and walked out into the corridor. He rang for the elevator.

“Going out already, suh?” the operator said, as the guest stepped into his car.

The man held up his hand in an unmistakable “Wait a minute” gesture. “I don’t want to go anywhere. Just want to talk to you for a couple of minutes, Moses.”

“Me, suh?”

“Yes, if you don’t mind.”

The operator turned his head, looking squarely at the man standing behind him. Waiting.

“My name’s Dett,” the tall man said, extending his hand to the operator. “Walker Dett.”

“It’s my pleasure to know you, Mr. Dett,” the operator said, palming the five-dollar bill as smoothly as he handled the elevator car. “Anything you need around here, you just-”

“You had time, size me up yet?”

“No, suh. It ain’t my place to be-”

“You’re a man who keeps his eyes open, I can tell.”

“Now, I don’t know nothing about that, suh. All I can see, you some kind of a businessman. A serious businessman,” the operator said. He kept his hand on the lever, ears alert for the buzzer which would summon the car.

“That’s right,” Dett said. “I’m here on business. And in my line of work, you know what’s really valuable?”

“No, suh.”

“Information. Every workingman needs his tools. And information, that’s a tool, isn’t it?”

“Sure could be, suh.”

“Some people, they think, in a hotel, it’s the desk clerk that knows everything that goes on. Others, they think it’s the bellhops. Some, they read too many paperback books, they think it’s the house dick. But you know what I think?”

“No, suh,” the elderly man said, evenly. “I don’t know what you think.”

“I think it’s not the job you do, it’s how long you’ve been doing it that makes you the man in the know. I think, a man gets to be a certain age, instead of people having respect, instead of them listening to him, they talk around him like he’s not even in the room. Like he’s wallpaper. A man like that, he gets to hear all kinds of things. You think I could be right?”

“Yes, suh. I believe you could be.”

“And a man like that, he’s not just worth something for what he knows; he’s worth double, because people don’t know he knows. Could I be right about that, too?”

“You surely could, suh.”

“You know what a ‘consultant’ is, Moses?”

“No, suh. I never heard of one.”

“Well, a consultant is a man you go to for advice. You ask him questions, he’s got answers. You ask him how to solve certain problems, he’s got the solutions. Man like that, he could make a good living, doing what he does.”

“Is that what you do, suh?”

“I think,” Dett said, tucking another five-dollar bill into the breast pocket of the operator’s blazer, “that’s what you do.”

The buzzer sounded. The two men exchanged a quick look. Dett stepped out of the elevator car, and the operator slid the lever to the “down” position.

1959 September 29 Tuesday 12:25

The knock on the door of Room 809 was that of an experienced bellhop-firm and deferential at the same time.

“Come on in,” Dett called from behind the partially opened bathroom door. He had positioned himself so that the medicine cabinet’s mirror gave him a clear view of the doorway. As the bellhop closed the door behind him, Dett slipped the derringer he had been holding into the pocket of his slacks and came out, giving his hands a finishing touch with the washcloth he carried.

“Here’s your liquor, sir. I don’t know how you takes it, so I brought you some ice, just in case,” the bellhop said, holding up a small chrome bucket.

At a nod from Dett, the bellhop placed the bottle and the ice bucket on top of a chest of drawers. Next to it, he ostentatiously deposited the change from the ten dollars he had been entrusted with.

“There’s too much there,” Dett said.

“Too much? But, sir, you said a fifth.”

“Too much money, Rufus,” Dett said. “You’re about a dollar heavy, the way I see it.”

“Thank you, sir,” the bellhop said. “I could tell you was a gent from the minute you checked in. You want me to pour you one now?”

“Just about so much,” Dett said, indicating a generous inch with his thumb and forefinger. “Over the rocks.”

“There you go, sir.”

“Thanks.”

“Yes, sir. If you need anything else…?”

“What hours do you work?”

“Me? Well, my regular shift is six to six. But I never mind putting in no extra time, if it’s needed. Everybody got to do that, even Mister Carl-that’s the deskman.”

“I got it,” Dett said, carrying his drink over to the room’s only easy chair and sitting down. It was clearly a dismissal.

The bellhop started for the door, then turned slightly, his eyes on the carpet. “Sir, what I said about needing anything else? That don’t have to be from the hotel, sir.”

“I don’t want any-”

“No, sir, I understand. Man like you, he don’t want no colored girl. But I got kind of an… arrangement, like. Make one phone call, get you anything up here you might want.”

“I’ll remember,” Dett said.

1959 September 29 Tuesday 12:36

As soon as the bellhop left, Dett closed the curtains. Then he opened the smaller of his two suitcases, took out a wooden wedge, and walked over to the door. He kicked the wedge under the door, then turned the knob and pulled it toward him. Even against strong pressure, the wedge held securely.

Turning his back on the door, Dett moved to the window, parted the curtains a slit, and peered outside. He glanced at his watch, then carried the untouched bourbon into the bathroom and emptied it into the sink, ran hot water over the ice cubes, and returned the unwashed glass to the top of the bureau. Moving methodically, he filled a second glass with fresh ice cubes and added tap water.

From the larger suitcase, Dett took a box of soda crackers. He drank a little of the water, then began eating, alternating the slow, thorough chewing of each bite with a sip of water.

Finished, he took a series of shallow breaths through his nose, pressing the first two fingers of each hand hard against his diaphragm as he exhaled.

Dett closed his eyes. A nerve jumped in his right cheek, so forcefully that it lifted the corner of his mouth. He continued the breathing, going deeper and deeper, until he fell asleep.

1959 September 29 Tuesday 17:09

When Dett opened his eyes, the room was dark, but it was the artificial darkness of closed curtains. The luminescent dial on his wristwatch told him it was just past five; his body told him that it was afternoon. Dett got up, used the bathroom, and drank another glass of water.

Crossing over to the far wall, Dett again parted the curtains. He tried both windows, found they opened easily but only went up less than halfway, held in place by metal stoppers in the channels. Behind the hotel was an alley, on the other side of which was the back side of an undistinguished brick building.

Dett took a street map from his suitcase, turning it in his hands until he was oriented to his own location. Office building, he said to himself, looking out the window. Probably goes dark after they close for the day.

Dett picked up the phone, dialed “0,” and told the hotel operator he wanted the front desk.

Connected, he asked the foppish clerk if he could get a sandwich sent up to his room.

“Certainly, Mr. Dett,” the desk clerk said, pridefully. “At the Claremont, our kitchen is always open until one in the morning, for anything from a snack to a full-course meal. And you can get a breakfast order anytime after six as well. Just tell me what you’d like, and I’ll have it sent right up.”

“I’d appreciate that,” Dett said. He ordered a steak sandwich, a side of French fries, and two bottles of Coke. Then he undressed, took a quick shower, and put on fresh clothes.

When the knock came, twenty minutes later, Dett wasn’t surprised to see Rufus on the other side of the threshold.

“You do all kinds of work around here, don’t you?” he said to the bellhop.

“I tell you the truth, sir. They got a boy in the kitchen, supposed to deliver meals to guests. But I got this…”

“Arrangement?” Dett said, smiling thinly.

“Yes, sir. I see you know how things work in hotels.”

“How much of a piece does that Nancy-boy take?”

“Mister Carl? The way he work it, end of my shift, every dollar I get, he supposed to get a dime.”

“He must do all right for himself, then.”

“You mean, he got the same deal with all the boys? Yes, sir. He sure do. Man like him, he in a powerful position around here.”

“Knows what’s going on, huh?”

“Knows it all, sir. I swear, sometimes I think he got secret passageways or something. We had this little game going in the basement,” the bellhop said, miming shaking a pair of dice in his closed hand. “Just a few of the boys, on our break, you know? Well, one day, I come into work, Mister Carl, he tells me there’s a toll due. You see how he is?”

“Not yet, I don’t.”

“I don’t follow you, sir.”

“How much of a toll was he charging?”

“Oh. Well, he said it would cost a dollar.”

“For every game.”

“Yes, sir.”

“So you stopped playing down there.”

“That’s right. How you know-? I mean, I apologize, sir. I didn’t mean no backtalk. Just surprised, is all.”

“Remember you asked me, did I see how he was? The desk clerk? Well, now I see how he is. Dumb.”

“Dumb? No, sir. Mister Carl, he a pretty slick-”

“If he charged you a quarter for every game, how much would he have made?”

“Well, we used to play every day, so…”

“Right. And how much is he getting from your games, now?”

“He ain’t… Oh, I see where you coming from, sir. Mister Carl, maybe he not so smart after all.”

“Let’s see if you are,” Dett said, handing the bellhop two one-dollar bills. “If Carl gets a piece of this, I’ll be real disappointed in you, Rufus.”

“You ain’t gonna have no cause to ever be disappointed in me, sir. My momma only raised but one fool, and that was my brother.”

1959 September 29 Tuesday 18:19

The guest in Room 809 opened the steak sandwich carefully.

He removed the lettuce and tomato, examining each in turn. Dett rolled his right shoulder-a small knife slid out of his sleeve and into his hand. He thumbed the knife open, then meticulously trimmed the outer edges of the lettuce, cored the slice of tomato, and removed every visible trace of fat from the meat before he reassembled the sandwich.

Dett picked up all the discarded pieces, carried them to the bathroom, and dropped them into the toilet. He flushed, checked to see if everything had disappeared, then washed his hands.

It took him almost forty-five minutes to eat the sandwich and French fries. He spaced sips of Coke evenly throughout, taking the final one after he swallowed the last of the sandwich.

Dett poured approximately three shots of the Four Roses into a glass. He carried it to the bathroom, emptied the contents into the toilet, and flushed again.

Then he sat and waited for darkness to bloom.

1959 September 29 Tuesday 21:09

Walker Dett washed his hands again, put on a tie, pocketed his room key, and walked out into the corridor.

“Evening, suh,” the elevator operator said, as he slid back the grillework for Dett to enter.

“Evening, Moses,” the man said. “I think I’ll take a little walk, help me digest my dinner.”

“Yes, suh,” said the operator, sliding the lever toward the “down” position.

Dett stepped close to the operator, holding out his palm and tilting his head in a “Wait a minute” gesture. The operator’s hand stopped the lever a fraction short of engagement.

“This elevator, it goes all the way to the basement?” Dett said, quietly.

“No, suh. Only the service car goes there.”

“But there’s no operator for that one, right?”

“That’s right,” the elderly man said, not surprised this quiet-voiced stranger would know such things.

“Can anyone just get in and run it, or do you need a key?”

“Used to be, like you say, anyone could just use it. But when Mister Carl took over-that was a few years after the war, if I remember right-he said that wouldn’t do. So now, you want to use the freight car, you got to ask Mister Carl, and he loans you the key.”

“But he’s not the only one who has one?”

“Oh no, suh. Nothing could run if things was like that. Plenty folks got keys. They has one in the kitchen, the maintenance man has one, the maids-they don’t like them riding the same cars as the guests, you know-the house cop… lots of folks, I bet. Me, I got one myself.”

“Thanks, Moses,” Dett said, moving his head slightly. The operator moved the lever a notch, and the car began to descend.

1959 September 29 Tuesday 21:59

Dett left the elevator car and walked over to the front desk.

“Everything satisfactory, Mr. Dett?” the clerk asked.

“It’s fine,” Dett assured him. “I was just going to take a little walk, work off my dinner.” He patted his stomach for emphasis. “A little fresh air never hurt anyone.”

“I couldn’t agree more,” the desk clerk said. “In fact, I’m somewhat of a physical-culture enthusiast myself.”

Dett nodded slightly, as if acknowledging the obvious. “This area,” he asked, “it’s safe at night?”

“This part of town? Absolutely! Now, there are some sections I certainly wouldn’t go myself, even in broad daylight. I’m sure you know what I mean…?”

“Sure.”

“So long as you stay within, oh, a ten-block radius, I’d say, you’ll find Locke City a wonderfully quiet town,” Carl said, smoothly.

1959 September 29 Tuesday 22:28

Dett strolled the broad avenue at a leisurely pace, his eyes on the passing traffic. In the time it took him to cover a half-dozen blocks, he spotted two police cars-black ’58 Ford sedans with white doors and roofs-blending unaggressively with the traffic flow. Guard dogs, big enough to send a message without barking.

A message received, Dett noted. The wide, clean sidewalk was devoid of loiterers. No hookers looking for trade, no teenage punks leaning against the buildings, no panhandlers. Nothing but respectably dressed citizens, mostly in couples, and very few of those.

Dett stayed in motion, all the while watching, clocking, measuring. He walked down a side street, then turned into an alley opening. When that dead-ended, he retraced his steps, noting how deserted the whole area had suddenly become. He glanced at his watch: ten-fifty-seven. Somewhere in this town, action was probably just getting started, he thought. But not around here…

Relying on his memory of the street map, Dett found his way to the office building he had observed from his hotel window. Positioning himself so that he could view the back of the hotel, he noted the absence of fire escapes. He turned a corner and checked again. Sure enough, each floor had a fire exit at the end of the corridor, on either side, leading to a series of metal staircases that formed a Z-pattern all the way down to the second floor. The final set of stairs would have to be released manually.

Dett turned slowly, scanning the area. His eyes picked up another alley opening, halfway down the block. They can’t all dead-end, he thought to himself, moving deliberately through the darkness, eyes alert for trail markers.

As Dett entered the alley, blotchy shadows told him that a source of light was somewhere in the vicinity. Maybe a streetlight positioned close to the other end? As he neared what he sensed to be the exit, the red glow of a cigarette tip flashed a warning. Dett took a long, shallow breath through his nose, sending a neural message to his neck and shoulder muscles to relax, deliberately opening receptor channels he trusted to watch his back.

He slowed his pace imperceptibly, and casually slipped his right hand into his pants pocket.

Two of them, Dett registered. As he got closer, his sense-impression was confirmed. They were in their late teens or early twenties; one, the smoker, sitting on a wooden milk crate, the other leaning against the alley wall, arms folded across his chest. Jackrollers, Dett said to himself. Must be a bar just around the corner, and some of the drunks use this alley as a shortcut.

Twenty yards. Ten. Dett kept coming, not altering his pace or his stance. His ears picked up the sound of speech, but he couldn’t make out the words. The man on the milk crate got to his feet, and the two of them moved off in the opposite direction, just short of a run.

Either they only work cripples, or they’re waiting for me just around the corner, one on each side of the alley, Dett thought. He spun on his heel and went back the way he had entered, still walking, but long-striding now, covering ground. At the alley entrance, Dett turned to his left, walked to the far corner, then squared the block, heading back toward where the alley would let out.

The sidewalk was dark except for a single streetlight only a few feet from the mouth of the alley-it seemed to know it was surrounded, and wasn’t putting up much of a fight. Dett crossed the street and walked on past. Not a sign of the two men.

He was nearly at the end of the long block when he noticed a faded blue-and-white neon sign in a small rectangular window. Enough of the letters still burned so Dett guessed at “Tavern,” but the rest was a mystery he wasn’t interested in solving.

Dett spent the next hour walking the streets, noting how many of the buildings seemed empty and abandoned.

1959 September 30 Wednesday 07:06

“He came back in around one in the morning,” Carl said. He was in the breakfast nook of a modest two-story house that occupied the mid-arc plot of a gently curving block, seated at a blue Formica kitchen table on a chair upholstered in tufted vinyl of the same shade.

“Your shift-your extra shift, I might add-was almost done,” a woman said, over her shoulder, focusing on her breakfast-preparation tasks. She was tall, fair-skinned, with sharp features and alert eyes, her white-blond hair worn in a tight bun.

“Not really,” Carl said, bitterly. “You know how Berwick is. Expecting him to come in on time…”

“Well, Carl, he may not last. They all seem to come and go.”

“He’s been there almost two years.”

“Still…”

“Mother, you don’t understand. It’s not just that he’s always late, it’s that he’s so… arrogant about it. As if he knows I’d never say anything to the manager about him.”

“Well, that’s not your way, Carl. You were not raised to be a talebearer.”

“Well, still, there’s plenty I could tell Mr. Hodges about Berwick, if I wanted to. It’s not just his lack of… dignity; he’s a filthy slob, Mother. You would not believe the state he leaves the desk in.”

“I know,” the woman said. “But that’s the way the world is, son. Some people act correctly, some people don’t. We are not responsible for anyone but ourselves.”

“I know he says things about me. Some of the colored boys, I can tell, by the way they look at me.”

“Are they disrespectful to you?”

“Well… no. I don’t mean anything they say. It’s just… I don’t know.”

“Carl,” the woman said, sternly, “there are always going to be people with big mouths and small minds.”

She brought a pale-blue plate to the table. On it were two perfectly poached eggs on gently browned toast, with the crusts removed.

“It isn’t like that everywhere,” Carl said.

“Oh, Carl, please. Not that again.”

“Well, it isn’t,” the not-so-young-anymore man insisted. “In some of the big cities-”

“You have roots here,” his mother interrupted. “You have a place, a place where you belong. A fine job, a lovely home…”

“I know, Mother. I know.”

“Sometimes, I get so worried about you, Carl. Every time you go on one of your vacations, I can’t even sleep, I’m so terrified.”

“There’s no reason to be frightened, Mother,” Carl said, resentfully. “I know my way around places a lot bigger than Locke City will ever be.”

“Oh, Carl,” the woman said, “I know you can take care of yourself. I raised you to be a competent man, a man who knows how to deal with whatever situation may come up in life.”

“Then why do you always get so-?”

“I worry… I just worry that, one day, you’ll go on vacation and you won’t come back.”

“That’s ridiculous.”

“Why is it so ridiculous, son? With your experience, you could get a job in a place like Chicago very easily.”

“Not Chicago,” Carl muttered.

“What?”

“I said, ‘Not Chicago,’ Mother. If I was going to live someplace else, it would be far away. New York. Or maybe San Francisco.”

“I couldn’t bear that,” she said, fidgeting with the waistband of her apron.

“Don’t be so dramatic, Mother. You know I would never leave you here alone. We could sell this house, and find a perfectly fine place somewhere else.”

“Carl, if I had to leave Locke City, I would just die. All my friends are here. My own mother, your Grandmother Tel, is an old woman now. How many years could she have left? Without me driving over to her place to do for her, why, she’d end up in one of those horrible old-age homes. And there’s my church. Our church, if you still went with me. My bridge club. My gardening group. I was born and raised only a few miles from this very house. There’s some flowers you just can’t transplant; they wouldn’t survive. And your father-”

“Yes, I miss him, too,” Carl said, sullenly.

“There is no reason to be so spiteful, Carl. I know you and your father had your differences, but he’s been gone a long time. And I always protected you, didn’t I?”

“You did,” Carl said, blinking his eyes rapidly. “Come on, Mother. Sit down with me. I want to tell you all about the mysterious Mr. Walker Dett.”

1959 September 30 Wednesday 08:11

Sun slanted through the partially drawn curtains of Room 809. Dett opened his eyes, instantly awake. He was on the floor, the double bed between him and the wedged door. Before going to sleep, he had balanced a quarter on the doorknob, and positioned a large glass ashtray beneath it. Had anyone tried the door while he slept, the coin would have dropped into the glass, alerting Dett but not the intruder.

Between the carpeted floor and the blanket and pillows he had removed from the bed, Dett had been quite comfortable. He was positioned on his side, back against the wall beneath the window. The derringer in his right hand looked as natural as a child’s teddy bear.

Dett got to his feet, pulled the tightly fitted sheet off the mattress, then deposited it at the foot of the bed, along with the blanket and the pillowcases he had removed to construct his sleeping quarters. He plucked the quarter from the doorknob, returned the ashtray to the writing desk, and lit a cigarette. While it was burning, he emptied some more of the Four Roses into the sink.

After a shower and shave, Dett telephoned room service and ordered breakfast and a newspaper, specifying the local. While he waited, he dressed-another plain dark suit, another carefully knotted tie, this time a sober shade of blue.

Three eggs, yolks broken and fried over hard, four strips of bacon, a side of hash-brown potatoes, two glasses of orange juice, and a basket of biscuits took him more than an hour to consume.

Dett carried the breakfast tray outside his room and left it on the floor, next to his door. He went back inside and sat down to read the paper, turning first to the personals column-in case Whisper had a message for him.

A few minutes later, the door opened and a cocoa-colored young woman in a white maid’s smock walked in.