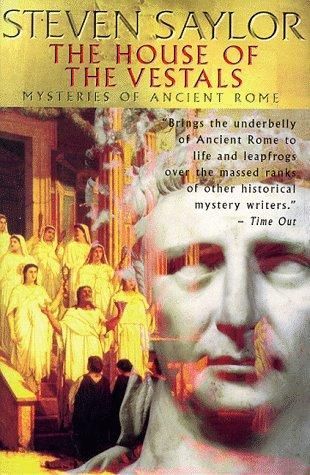

"The House Of The Vestals" - читать интересную книгу автора (Saylor Steven)

|

Steven Saylor

The House Of The Vestals

DEATH WEARS A MASK

"Eco," I said, "do you mean to tell me that you have never seen a play?"

He looked up at me with his big brown eyes and shook his head.

"Never laughed at the bumbling slaves who have a falling-out? Never swooned to see the young heroine abducted by pirates? Never thrilled at the discovery that our hero is the secret heir to a vast fortune?"

Eco's eyes grew even larger, and he shook his head more vigorously.

"Then there must be a remedy, this very day!" I said.

It was the Ides of September, and a more beautiful autumn day the gods had never fashioned. The sun shone warmly on the narrow streets and gurgling fountains of Rome; a light breeze swept, up from the Tiber, cooling the seven hills; the sky above was a bowl of purest azure, without a single cloud. It was the twelfth day of the sixteen days set aside each year for the Roman Festival, the city's oldest public holiday. Perhaps Jupiter himself had decreed that the weather should be so perfect; the holiday was in his honor.

For Eco, the festival had been an endless orgy of discoveries. He had seen his first chariot race in the Circus Maximus, had watched wrestlers and boxers in the public squares, had eaten his first calf's-brain-and-almond sausage from a street vendor. The race had thrilled him, mostly because he thought the horses so beautiful; the pugilists had bored him, since he had seen plenty of brawling-in public before; the sausage had not agreed with him (or perhaps his problem was the spiced green apples on which he gorged himself afterward).

It was four months since I had rescued Eco in an alley in the Subura, from a gang of boys pursuing him with sticks and cruel jeers. I knew a little of his history, having met him briefly in my investigations for Cicero that spring. Apparently his widowed mother had chosen to abandon little Eco in her desperation, leaving him to fend for himself. What else could I do but take him home with me?

He struck me as exceedingly clever for a boy often. I knew he was ten, because whenever he was asked, he held up ten fingers. Eco could hear (and add) perfectly well, even if his tongue was useless.

At first, his muteness was a great handicap for us both. (He had not been born mute, but had been made that way, apparently by the same fever that claimed his father's life.) Eco is a skillful mime, to be sure, but gestures can convey only so much. Someone had taught him the letters, but he could read and write only the simplest words. I had begun to teach him myself, but the going, was made harder by his speechlessness.

His practical knowledge of the streets of Rome was deep but narrow. He knew all the back entrances to all the shops in the Subura, and where the fish and meat vendors down by the Tiber left their scraps at the end of the day. But he had never been to the Forum or the Circus Maximus, had never heard a politician declaim (lucky boy!) or witnessed the spectacle of the theater. I spent many hours showing him the city that summer, rediscovering its marvels through the wide eyes of a ten-year-old boy.

So it was that, on the twelfth day of the Roman Festival, when a crier came running through the streets announcing that the company of Quintus Roscius would be performing in an hour, I determined that we should not miss it.

"Ah, the company of Roscius the Comedian!" I said. "The magistrates in charge of the festival have spared no expense. There is no more famous actor today than Quintus Roscius, and no more renowned troupe of performers than his!"

We made our way from the Subura down to the Forum, where holiday crowds thronged the open squares. Between the Temple of Jupiter and the Senian Baths, a makeshift theater had been erected. Rows of benches were set before a wooden stage that had been raised in the narrow space between the brick walls.

"Some day," I remarked, "a rabble-rousing politician will build the first permanent theater in Rome. Imagine that, a proper Grecian-style theater made of stone, as sturdy as a temple! The old-fashioned moralists will be scandalized-they hate the theater because it comes from Greece, and they think that all things Greek must be decadent and dangerous. Ah, we're early-we. shall have good seats."

The usher led us to an aisle seat on a bench five rows back from the stage. The first four rows had been partitioned by a rope of purple cloth, set aside for those of senatorial rank. Occasionally the usher tromped down the aisle, followed by some toga-clad magistrate and his party, and pulled aside the rope to allow them access to the benches.

While the theater slowly filled around us, I pointed out to Eco the details of the stage. Before the first row of benches there was a small open space, the orchestra, where the musicians would play; three steps at either side led up to the stage itself. Behind the stage and enclosing it on either side was a screen of wood with a folding door in the middle and other doors set into the left and right wings. Through these doors the actors would enter and exit. Out of sight, behind the stage, the musicians could be heard warming up their pipes, trilling snatches of familiar tunes.

"Gordianus!"

I turned to see a tall, thin figure looming over us.

"Statilius!" I cried. "It's good to see you."

"And you as well. But who is this?" He ruffled Eco's mop of brown hair with his long fingers.

"This is Eco," I said.

"A long-lost nephew?"

"Not exactly."

"Ah, an indiscretion from the past?" Statilius raised an eyebrow.

"Not that, either." My face turned hot. And yet I suddenly wondered how it would feel to say, "Yes, this is my son." Not for the first time I considered the possibility of adopting Eco legally- and as quickly banished the thought from my mind. A man like myself, who often risks death, has no business becoming a father; so I told myself. If I truly wanted sons, I could have married a proper Roman wife long ago and had a houseful by now. I quickly changed the subject.

"But Statilius, where is your costume and your mask? Why aren't you backstage, getting ready?" I had known Statilius since we were boys; he had become an actor in his youth, joining first one company and then another, always seeking the training of established comedians. The great Roscius had taken him on a year before.

"Oh, I still have plenty of time to get ready."

"And how is life in the company of the greatest actor in Rome?"

"Wonderful, of course!"

I frowned at the note of false bravado in his voice.

"Ah, Gordianus, you always could see through me. Not wonderful, then-terrible! Roscius-what a monster! Brilliant, to be sure, but a beast! If I were a slave I'd be covered with bruises. Instead, he whips me with his tongue. What a taskmaster! The man is relentless, and never satisfied. He makes a man feel no better than a worm. The galleys or the mines could hardly be worse. Is it my fault that I've grown too old to play heroines and haven't yet the proper voice to be an old miser or a braggart soldier? Ah, perhaps Roscius is right. I'm useless-talentless-I bring the whole company into disrepute."

"Actors are all alike," I whispered to Eco. "They need more coddling than babies." Then to Statilius: "Nonsense! I saw you in the spring, at the Festival of the Great Mother, when Roscius put on The Brothers Menaechmus. You were brilliant playing the twins."

"Do you really think so?"

"I swear it. I laughed so hard I almost fell off the bench."

He brightened a bit, then frowned. "I wish that Roscius thought so. Today I was all set to play Euclio, the old miser-"

"Ah, then we're seeing The Pot of Gold!"

"Yes."

"One of my favorite plays, Eco. Quite possibly Plautus's funniest comedy. Crude, yet satisfying-"

"I was to play Euclio," Statilius said rather sharply, drawing the conversation back to himself, "when suddenly, this morning, Roscius explodes into a rage and says that I have the role all wrong, and that he can't suffer the humiliation of seeing me bungle it in front of all Rome. Instead I'll be Megadorus, the next-door neighbor."

"Another fine role," I said, trying to remember it.

"Fah! And who gets the plum role of Euclio? That parasite Panurgus-a mere slave, with no more comic timing than a slug!" He abruptly stiffened. "Oh no, what's this?"

I followed his gaze to the outer aisle, where the usher was leading a burly, bearded man toward the front of the theater. A blond giant with a scar across his nose followed close behind- the bearded man's bodyguard; I know a hired ruffian from the Subura when I see one. The usher led them to the far end of our bench; they stepped into the gap and headed toward us to take the empty spot beside Eco.

Statilius bent low to hide himself and groaned into my ear. "As if I hadn't enough worries-it's that awful moneylender Flavius and one of his hired bullies. The only man in Rome who's more of a monster than Roscius."

"And just how much do you owe this Flavius?" I began to say, when suddenly, from backstage, a roaring voice rose above the discordant pipes.

"Fool! Incompetent! Don't come to me now saying you can't remember the lines!"

"Roscius," Statilius whispered, "screaming at Panurgus, I hope. The man's temper is terrible."

The central door on the stage flew open, revealing a short, stocky man already dressed for the stage, wearing a splendid cloak of rich white fabric. His lumpy, scowling face was the sort to send terror into an underling's soul, yet this was, by universal acclaim, the funniest man in Rome. His legendary squint made his eyes almost invisible, but when he looked in our direction, I felt as if a dagger had been thrown past my ear and into the heart of Statilius.

"And you!" he bellowed. "Where have you been? Backstage, immediately! No, don't bother to go the long way round- backstage, now!" He gave commands as if he were speaking to a dog.

Statilius hurried up the aisle, leaped onto the stage and disappeared backstage, closing the door behind him-but not, I noticed, before casting a furtive glance at the newcomer who had just seated himself beside Eco. I turned and looked at Flavius the moneylender, who returned my curious gaze with a scowl. He did not look like a man in the proper mood for a comedy.

I cleared my throat. "Today you'll see The Pot of Gold," I said pleasantly, leaning past Eco toward the newcomers. Flavius gave a start and wrinkled his bushy brows. "One of Plautus's very best plays, don't you think?"

Flavius parted his lips and peered at me suspiciously. The blond bodyguard looked at me with an expression of supreme stupidity.

I shrugged and turned my attention elsewhere.

From the open square behind us, the crier made his last announcement. The benches filled rapidly. Latecomers and slaves stood wherever they could, crowding together on tiptoe. Two musicians stepped onto the stage and descended to the orchestra, where they began to blow upon their long pipes.

A murmur of recognition passed through the crowd at the familiar strains of the miser Euclio's theme, the first indication of the play we were about to see. Meanwhile the usher and the crier moved up and down the aisles, playfully hushing the noisier members of the audience.

At length the overture was finished. The central door on the stage rattled open. Out stepped Roscius, wearing his sumptuous white cloak, his head obscured by a mask of grotesque, happy countenance. Through the holes I glimpsed his squinting eyes; his mellow voice resonated throughout the theater.

"In case you don't know who I am, let me briefly introduce myself," he said. "I am the Guardian Spirit of this house- Euclio's house. I have been in charge of this place now for a great many years…" He proceeded to deliver the prologue, giving the audience a starting point for the familiar story-how the grandfather of Euclio had hidden a pot of gold beneath the floorboards of the house, how Euclio had a daughter who was in love with the next-door neighbor's nephew and needed only a dowry to be happily married, and how he, the Guardian Spirit, intended to guide the greedy Euclio to the pot of gold and so set events in motion.

I glanced at Eco, who stared up at the masked figure enraptured, hanging on every word. Beside him, the moneylender Flavius wore the same unhappy scowl as before. The blond bodyguard sat with his mouth open, and occasionally reached up to pick at the scar across his nose.

A muffled commotion was heard from backstage. "Ah," said Roscius in a theatrical whisper, "there's old Euclio now, pitching a fit as usual. The greedy miser must have located the pot of gold by now, and he wants to count his fortune in secret, so he's turning the old housekeeper out of the house." He quietly withdrew through the door in the right wing.

Through the central door emerged a figure wearing an old man's mask and dressed in bright yellow, the traditional color for greed. This was Panurgus, the slave-actor, taking the plum leading role of the miser Euclio. Behind him he dragged another actor, dressed as a lowly female slave, and flung him to the middle of the stage. "Get out!" he shouted. "Out! By Hades, out with you, you old snooping bag of bones!"

Statilius had been wrong to disparage Panurgus's comic gifts; already I heard guffaws and laughter around me.

"What have I done? What? What?" cried the other actor.

His grimacing feminine mask was surmounted by a hideous tangled wig. His gown was in tatters about his knobby knees. "Why are you beating a long-suffering old hag?"

"To give you something to be long-suffering about, that's why! And to make you suffer as much as I do, just looking at you!" Panurgus and his fellow actor scurried about the stage, to the uproarious amusement of the audience. Eco bounced up and down on the bench and clapped his hands. The moneylender and his bodyguard sat with their arms crossed, unimpressed.

But why must you drive me out of the house?

EUCLIO: Why? Since when do I have to give you a reason?

You're asking for a fresh crop of bruises!

HOUSEKEEPER: Let the gods send me jumping off a cliff if I'll put up with this sort of slavery any longer!

EUCLIO: What's she muttering to herself? I've a good mind to poke your eyes out, you damned witch!

At length the slave woman disappeared and the miser went back into his house to count his money, the neighbor Megadorus and his sister Eunomia occupied the stage. From the voice, it seemed to me that the sister was played by the same actor who had performed the cringing slave woman; no doubt he specialized in female characters. My friend Statilius, as Megadorus, performed adequately, I thought, but he was not in the same class with Roscius, or even with his rival Panurgus. His comic turns inspired polite guffaws, not raucous laughter.

EUNOMIA: Dear brother, I've asked you out of the house to have a little talk about your private affairs.

MEGADORUS: How sweet! You are as thoughtful as you are beautiful. I kiss your hand.

EUNOMIA: What? Are you talking to someone behind me?

MEGADORUS: Of course not. You're the prettiest woman I know!

EUNOMIA: Don't be absurd. Every woman is uglier than every other,in one way or another.

MEGADORUS: Mmm, but of course; whatever you say…

EUNOMIA: Now give me your attention. Brother dear, I should like to see you married-

MEGADORUS: Help! Murder! Ruin!

EUNOMIA:Oh, quiet down!

Even this exchange, usually so pleasing to the crowd, evoked only lukewarm titters. My attention strayed to Statilius's costume, made of sumptuous blue wool embroidered with yellow, and to his mask, with its absurdly quizzical eyebrows. Alas, I thought, it is a bad sign when a comedian's costume is of greater interest than his delivery. Poor Statilius had found a place with the most respected acting troupe in Rome, but he did not shine there. No wonder the demanding Roscius was so intolerant of him!

Even Eco grew restless. Next to him, the moneylender Flavius leaned over to whisper something in the ear of his blond bodyguard-disparaging the talents of the actor who owed him money, I thought.

At length the sister exited; the miser returned to converse with his neighbor. Seeing the two of them together on the stage-Statilius and his rival, Panurgus-the gulf between their talents was painfully clear. Panurgus as Euclio stole the scene completely, and not just because his lines were better.

EUCLIO: So you wish to marry my daughter. Good enough-but you must know I haven't so much as a copper to donate to her dowry.

MEGADORUS: I don't expect even half a copper. Her virtue and good name are quite enough.

EUCLIO: I mean to say, it's not as if I'd just happened to have found some, oh, buried treasure in my house… say, a pot of gold buried by my grandfather, or-

MEGADORUS: Of course not – how ridiculous! Say no more.You'll give your daughter to me, then?

EUCLIO:Agreed. But what's that? Oh no, I'm ruined!

MEGADORUS: Jupiter Almighty, what's wrong?

EUCLIO: I thought I heard a spade… someone digging…

MEGADORUS: Why, it's only a slave I've got digging up some roots in my garden. Calm down, good neighbor…

I inwardly groaned for my friend Statilius; but if his delivery was flat, he had learned to follow the master's stage directions without a misstep. Roscius was famous not only for embellishing the old comedies with colorful costumes and masks to delight the eyes, but for choreographing the movements of his actors. Statilius and Panurgus were never static on the stage, like the actors in inferior companies. They circled one another in a constant comic dance, a swirl of blue and yellow.

Eco tugged at my sleeve. With a shrug of his shoulder he gestured to the men beside him. Flavius was again whispering in the bodyguard's ear; the big blond was wrinkling his eyebrows, perplexed. Then he rose and lumbered toward the aisle. Eco drew up his feet, but I was too slow. The monster stepped on my foot. I let out a howl. Others around me started doing the same, thinking I was badgering the actors. The blond giant made no apology at all.

Eco tugged at my sleeve. "Let it go, Eco," I said. "One must learn to live with rudeness in the theater."

He only rolled his eyes and crossed his arms in exasperation. I knew that gesture: if only he could speak!

On the stage, the two neighbors concluded their plans for Megadorus to wed the daughter of Euclio; with a shrilling of pipes and the tinkling of cymbals, they left the stage and the first act was done.

The pipe players introduced a new theme. After a moment, two new characters appeared on stage. These were the quarreling cooks, summoned to prepare the wedding feast. A Roman audience delights in jokes about food and gluttony, the cruder the better. While I groaned at the awful puns, Eco laughed aloud, making a hoarse, barking sound.

In the midst of the gaiety, my blood turned cold. Above the laughter, I heard a scream.

It was not a woman's scream, but a man's. Not a scream of fear, but of pain.

I looked at Eco, who looked back at me. He had heard it, too. No one else in the audience seemed to have noticed, but the actors on stage must have heard something. They bungled their lines and turned uncertainly toward the door, stepping on one another's feet. The audience only laughed harder at their clumsiness.

The quarreling cooks came to the end of their scene and disappeared backstage.

The stage was empty. There was a pause that grew longer and longer. Strange, unaccountable noises came from backstage-muffled gasps, confused shuffling, a loud shout. The audience began to murmur and shift restlessly on the benches.

At last the door from the left wing opened. Onto the stage stepped a figure wearing the mask of the miser Euclio. He was dressed in bright yellow as before, but it was a different cloak. He threw his hands in the air. "Disaster!" he cried. I felt a cold shiver down my spine.

"Disaster!" he said again. "A daughter's marriage is a disaster! How can any man afford it? I've just come back from the market, and you wouldn't believe what they're charging for lamb-an arm and a leg for an arm and a leg, that's what they want…"

The character was miserly Euclio, but the actor was no longer Panurgus; it was Roscius behind the mask. The audience seemed not to notice the substitution, or at least not to mind it; they started laughing almost immediately at the spectacle of poor Euclio befuddled by his own stinginess.

Roscius delivered the lines flawlessly, with the practiced comic timing that comes from having played a role many times, but I thought I heard a strange quavering in his voice. When he turned so that I could glimpse his eyes within the mask, I saw no sign of his famous squint. His eyes were wide with alarm. Was this Roscius the actor, frightened of something very real-or Euclio, afraid that the squabbling cooks would find his treasure?

"What's that shouting from the kitchen?" he cried. "Oh no, they're calling for a bigger pot to put the chicken in! Oh, my pot of gold!" He ran through the door backstage, almost tripping over his yellow cloak. There followed a cacophony of crashing pots.

The central door was thrown open. One of the cooks emerged onstage, crying out in a panic: "Help, help, help!"

It was the voice of Statilius! I stiffened and started to stand, but the words were only part of the play. "It's a madhouse in there," he cried, straightening his mask. He jumped from the stage and ran into the audience. "The miser Euclio's gone mad! He's beating us over the head with pots and pans! Citizens, come to our rescue!" He whirled about the central aisle until he came to a halt beside me. He bent low and spoke through his teeth so that only I could hear.

"Gordianus! Come backstage, now!"

I gave a start. Through the mask I looked into Statilius's anxious eyes.

"Backstage!" he hissed. "Come quick! A dagger-blood- Panurgus-murder!"

From beyond the maze of screens and awnings and platforms I occasionally heard the playing of the pipes and actor's voices raised in argument, followed by the muffled roar of the audience laughing. Backstage, the company of Quintus Roscius ran about in a panic, changing costumes, fitting masks onto one another's heads, mumbling lines beneath their breath, sniping at each other or exchanging words of encouragement, and in every other way trying to act as if this were simply another hectic performance and a corpse was not lying in their midst.

The body was that of the slave Panurgus. He lay on his back in a secluded little alcove in the alley that ran behind the Temple of Jupiter, The place was a public privy, one of many built in out-of-the-way nooks on the perimeter of the Forum. Screened by two walls, a sloping floor tilted to a hole that emptied into the Cloaca Maxima. Panurgus had apparently come here to relieve himself between scenes. Now he lay dead with a knife plunged squarely into his chest. Above his heart a large red circle stained his bright yellow costume. A sluggish stream of blood trickled across the tiles and ran down the drain.

He was older than I had thought, almost as old as his master, with gray in his hair and a wrinkled forehead. His mouth and eyes were open wide in shock; his eyes were green, and in death they glittered dully like uncut emeralds.

Eco gazed down at the body and reached up to grasp my hand. Statilius ran up beside us. He was dressed again in blue and held the mask of Megadorus in his hands. His face was ashen. "Madness," he whispered. "Bloody madness."

"Shouldn't the play be stopped?"

"Roscius refuses. Not for a slave, he says. And he doesn't dare tell the crowd. Imagine: a murder, backstage, in the middle of our performance, on a holiday consecrated to Jupiter himself, in the very shadow of the god's temple-what an omen! What magistrate would ever hire Roscius and the company again? No, the show goes on-even though we must somehow figure out how to fill nine roles with five actors instead of six. Oh dear, and I've never learned the nephew's lines…"

"Statilius!" It was Roscius, returning from the stage. He threw off the mask of Euclio. His own face was almost as grotesque, contorted with fury. "What do you think you're doing, standing there mumbling? If I'm playing Euclio, you have to play the nephew!" He rubbed his squinting eyes, then slapped his forehead. "But no, that's impossible-Megadorus and the nephew must be onstage at the same time. What a disaster! Jupiter, why me?"

The actors circled one another like frenzied bees. The dressers hovered about them uncertainly, as useless as drones. All was chaos in the company of Quintus Roscius.

I looked down at the bloodless face of Panurgus, who was beyond caring. All men become the same in death, whether slave or citizen, Roman or Greek, genius or pretender.

At last the play was over. The old bachelor Megadorus had escaped the clutches of marriage; miserly Euclio had lost and then recovered his pot of gold; the honest slave who restored it to him had been set free; the quarreling cooks had been paid by Megadorus and sent on their way; and the young lovers had been joyously betrothed. How this was accomplished under the circumstances, I do not know. By some miracle of the theater, everything came off without a hitch. The cast assembled together on the stage to roaring applause, and then returned backstage, their exhilaration at once replaced by the grim reality of the death among them.

"Madness," Statilius said again, hovering over the corpse.

Knowing how he felt about his rival, I had to wonder if he was not secretly gloating. He seemed genuinely shocked, but that, after all, could have been acting.

"And who is this?" barked Roscius, tearing off the yellow cloak he had assumed to play the miser.

"My name is Gordianus. Men call me the Finder."

Roscius raised an eyebrow and nodded. "Ah, yes, I've heard of you. Last spring-the case of Sextus Roscius; no relation to myself, I'm glad to say, or very distant, anyway. You earned yourself a name with parties on both sides of that affair."

Knowing the actor was an intimate of the dictator Sulla, whom I had grossly offended, I only nodded.

"So what are you doing here?" Roscius demanded.

"It was I who told him," said Statilius helplessly. "I asked him to come backstage. It was the first thing I thought of."

"You invited an outsider to intrude on this tragedy, Statilius? Fool! What's to keep him from standing in the Forum and announcing the news to everyone who passes? The scandal will be disastrous."

"I assure you, I can be quite discreet-for a client," I said.

"Oh, I see," said Roscius, squinting at me shrewdly. "But perhaps that's not a bad idea, provided you could actually be of some help."

"I think I might," I said modestly, already calculating a fee. Roscius was, after all, the most highly paid actor in the world. Rumor claimed he made as much as half a million sesterces in a single year. He could afford to be generous.

He looked down at the corpse and shook his head bitterly. "One of my most promising pupils. Not just a gifted artist, but a valuable piece of property. But why should anyone murder the slave? Panurgus had no vices, no politics, no enemies."

"It's a rare man who has no enemies," I said. I could not help but glance at Statilius, who hurriedly looked away.

There was a commotion among the gathered actors and stagehands. The crowd parted to admit a tall, cadaverous figure with a shock of red hair.

"Chaerea! Where have you been?" growled Roscius.

The newcomer looked down his long nose, first at the corpse, then at Roscius. "Drove down from my villa at Fidenae," he snapped tersely. "Axle on the chariot broke. Missed more than the play, it appears."

"Gaius Fannius Chaerea," whispered Statilius in my ear. "He was Panurgus's original owner. When he saw the slave had comic gifts he handed him over to Roscius to train him, as part-owner."

"They don't seem friendly," I whispered back.

"They've been feuding over how to calculate the profits from Panurgus's performances…"

"So, Quintus Roscius," sniffed Chaerea, tilting his nose even higher, "this is how you take care of our common property. Bad management, I say. Slave's worthless, now. I'll send you a bill for my share."

"What? You think I'm responsible for this?" Roscius squinted fiercely.

"Slave was in your care; now he's dead. Theater people! So irresponsible." Chaerea ran his bony fingers through his orange mane and shrugged haughtily before turning his back. "Expect my bill tomorrow," he said, stepping through the crowd to join a coterie of attendants waiting in the alley. "Or I'll see you in court."

"Outrageous!" said Roscius. "You!" He pointed a stubby finger at me. "This is your job! Find out who did this, and why. If it was a slave or a pauper, I'll have him torn apart. If it was a rich man, I'll sue him blind for destroying my property. I'll go to Hades before I give Chaerea the satisfaction of saying this was my fault!"

I accepted the job with a grave nod, and tried not to smile.

I could almost feel the rain of glittering stiver on my head.Then I glimpsed the contorted face of the dead Panurgus, and felt the full gravity of my commission. For a dead slave in Rome, there is seldom any attempt to find justice. I would find the killer, I silently vowed, not for Roscius and his silver, but to honor the shade of an artist cruelly cut down in his prime.

"Very well, Roscius. I'll need to ask some questions. See that no one in the company leaves until I'm done. I'd like to talk with you in private first. Perhaps a cup of wine would calm us both…"

Late that afternoon, I sat on a bench beneath the shade of an olive tree, on a quiet street not far from the Temple of Jupiter. Eco sat beside me, pensively studying the play of leafy shadows on the paving stones.

"So, Eco, what do you think.? Have we learned anything at all of value?"

He shook his head gravely.

"You judge too quickly," I laughed. "Consider: we last saw Panurgus alive during his scene with Statilius at the close of the first act. Then those two left the stage; the pipers played an interlude, and next the quarreling cooks came on. Then there was a scream. That must have been Panurgus, when he was stabbed. It caused a commotion backstage; Roscius checked into the matter and discovered the body in the privy. Word quickly spread among the others. Roscius put on the dead man's mask and a yellow cloak, the closest thing he had to match Panurgus's costume, which was ruined by blood, and rushed onstage to keep the play going. Statilius, meanwhile, put on a cook's costume so that he could jump into the audience and plead for my help.

"Therefore, we know at least one thing: the actors playing the cooks were innocent, as were the pipe players, because they were onstage when the murder occurred."

Eco made a face to show he was not impressed. "Yes, I admit, this is all very elementary, but to build a wall we must begin with a single brick. Now, who was backstage at the time of the murder, has no one to account for his whereabouts at the moment of the scream, and might have wanted Panurgus dead?"

Eco bounded up from the bench, ready to play the game. He performed a pantomime, jabbering with his jaw and waving his arms at himself.

I smiled sadly; the unflattering portrait could only be my talkative and self-absorbed friend Statilius. "Yes, Statilius must be foremost among the suspects, though I regret to say it. We know he had cause to hate Panurgus; so long as the slave was alive, a man of inferior talent like Statilius would never be given the best roles. We also learned, from questioning the company, that when the scream was heard, no one could account for Statilius's whereabouts. This may be only a coincidence, given the ordinary chaos that seems to reign backstage during a performance. Statilius himself vows that he was busy in a corner adjusting his costume. In his favor, he seems to have been truly shocked at the slave's death-but he might only be pretending. I call the man my friend, but do I really know him?" I pondered for a moment. "Who else, Eco?"

He hunched his shoulders, scowled and squinted. "Yes, Roscius was also backstage when Panurgus screamed, and no one seems to remember seeing him at that instant. It was he who found the corpse-or was he there when the knife descended? Roscius is a violent man; all his actors say so. We heard him shouting angrily at someone before the play began-do you remember? 'Fool! Incompetent! Why can't you remember your lines?' Others told me it was Panurgus he was shouting at. Did the slave's performance in the first act displease him so much that he flew into a rage, lost his head and murdered him? It hardly seems likely; I thought Panurgus was doing quite well. And Roscius, like Statilius, seemed genuinely offended by the murder. But then, Roscius is an actor of great skill."

Eco put his hands on his hips and his nose in the air and began to strut haughtily.

"Ah, Chaerea; I was coming to him. He claims not to have arrived until after the play was over, and yet he hardly seemed taken aback when he saw the corpse. He seems almost too un-flappable. He was the slave's original owner. In return for cultivating Panurgus's talents, Roscius acquired half-ownership, but Chaerea seems to have been thoroughly dissatisfied with the arrangement. Did he decide that the slave was worth more to him dead than alive? Chaerea holds Roscius culpable for the loss, and intends to coerce Roscius into paying him half the slave's worth in silver. In a Roman court, with the right advocate, Chaerea will likely prevail."

I leaned back against the olive tree, dissatisfied. "Still, I wish we had uncovered someone else in the company with as strong a motive, and the opportunity to have done the deed. Yet no one seems to have borne a grudge against Panurgus, and almost everyone could account for his whereabouts when the victim screamed.

"Of course, the murderer may be someone from outside the company; the privy where Panurgus was stabbed was accessible to anyone passing through the alley behind the temple. Yet Roscius tells us, and the others confirm, that Panurgus had almost no dealings with anyone outside the troupe-he didn't gamble or frequent brothels; he borrowed neither money nor other men's wives. His craft alone consumed him; so everyone says. Even if Panurgus had offended someone, the aggrieved party would surely have taken up the matter not with Panurgus but with Roscius, since he was the slave's owner and the man legally responsible for any misdeeds."

I sighed with frustration. "The knife left in his heart was a Common dagger, with no distinguishing features. No footprints surrounded the body. No telltale blood was found on any of the costumes. There were no witnesses, or none we know of. Alas!" The shower of silver in my imagination dried to a trickle; with nothing to show, I would be lucky to press Roscius into paying me a day's fee for my trouble. Even worse, I felt the shade of dead Panurgus watching me. I had vowed I would find his killer, and it seemed the vow was rashly made.

That night I took my dinner in the ramshackle garden at the center of my house. The lamps burned low. Tiny silver moths flitted among the columns of the peristyle. Sounds of distant revelry occasionally wafted up from the streets of the Subura at the foot of the hill.

"Bethesda, the meal was exquisite," I said, lying with my usual grace. Perhaps I could have been an actor, I thought.

But Bethesda was not fooled. She looked at me from beneath her long lashes and smiled with half her mouth. She combed one hand through the great unbound mass of her glossy black hair and shrugged an elegant shrug, then began to clear the table.

As she departed to the kitchen, I watched the sinuous play of her hips within her loose green gown. When I bought her long ago at the slave market in Alexandria, it had not been for her cooking. Her cooking had never improved, but in many other ways she was beyond perfection. I peered into the blackness of the long tresses that cascaded to her waist; I imagined the silver moths lost in those tresses, like twinkling stars in the blue-black firmament of the sky. Before Eco had come into my life, Bethesda and I had spent almost every night together, just the two of us, in the solitude of the garden…

I was startled from my reverie by a hand pulling at the hem of my tunic.

"Yes, Eco, what is it?"

Eco, reclining on the couch next to mine, put his fists together and pulled them apart, up and down, as if unrolling a scroll.

"Ah, your reading lesson. We had no time for it today, did we? But my eyes are weary, Eco, and yours must be, too. And there are other matters on my mind…"

He frowned at me in mock dejection until I relented." Very well. Bring that lamp nearer. What would you like to read tonight?"

Eco pointed at himself and shook his head, then pointed at me. He cupped his hands behind his ears and closed his eyes. He preferred it (and secretly, so did I) when I did the reading, and he could enjoy the luxury of merely listening. All that summer, on lazy afternoons and long summer nights, the two of us had spent many such hours in the garden. While I read Piso's history of Hannibal, Eco would sit at my feet and watch elephants among the clouds; while I declaimed the tale of the Sabine women, he would lie on his back and study the moon. Of late I had been reading to him from an old, tattered scroll of Plato, a cast-off gift from Cicero. Eco understood Greek, though he knew none of the letters, and he followed the subtleties of the philosopher's discourses with fascination, though occasionally in his big brown eyes I saw a glimmer of sorrow that he could never hope to engage in such debates himself.

"Shall I read more Plato, then? They say philosophy after dinner aids digestion."

Eco nodded and ran to fetch the scroll. He emerged from the shadows of the peristyle a moment later, gripping it carefully in his hands. Suddenly he stopped and stood statuelike with a strange expression on his face.

"Eco, what is it?" I thought for a moment that he was ill; Bethesda's fish dumplings and turnips in cumin sauce had been undistinguished, but hardly so bad as to make him sick. He stared straight ahead at nothing and did not hear me.

"Eco? Are you all right?" He stood rigid, trembling; a look which might have been fear or ecstasy crossed his face. Then he sprang toward me, pressed the scroll under my nose and pointed at it frantically.

"I've never known a boy to be so mad for learning," I laughed, but he was not playing a game. His expression was deadly serious. "But Eco, it's only the same volume of Plato that I've been reading to you off and on all summer. Why are you suddenly so excited?"

Eco stood back to perform his pantomime. A dagger thrust into his heart could only indicate the dead Panurgus.

"Panurgus and Plato-Eco, I see no connection."

Eco bit his lip and scrambled about, desperate to express himself. At last he ran into the house and back out again, clutching two objects. He dropped them onto my lap.

"Eco, be careful! This little vase is made of precious green glass, and came all the way from Alexandria. And why have you brought me a bit of red tile? This must have fallen from the roof…"

Eco pointed emphatically at each object in turn, but I could not see what he meant.

He disappeared again and came back with my wax tablet and stylus, upon which he wrote the words for red and green.

"Yes, Eco, I can see that the vase is green and the tile is red. Blood is red…" Eco shook his head and pointed to his eyes. "Panurgus had green eyes…" I saw them in my memory, staring lifeless at the sky.

Eco stamped his foot and shook his head to let me know that I was badly off course. He took the vase and the bit of tile from my lap and began to juggle them from hand to hand

"Eco, stop that! I told you, the vase is precious!"

He put them carelessly down and reached for the stylus again. He rubbed out the words red and green and in their place wrote blue. It seemed he wished to write another word, but could not think of how to spell it. He nibbled on the stylus and shook his head.

"Eco, I think you must have a fever. You make no sense at all."

He took the scroll from my lap and began to unroll it, scanning it hopelessly. Even if the text had been in Latin it would have been a tortuous job for him to decipher the words and find whatever he was searching for, but the letters were Greek and utterly foreign to him.

He threw down the scroll and began to pantomime again, but he was excited and clumsy; I could make no sense of his wild gesturing. I shrugged and shook my head in exasperation, and Eco suddenly began to weep with frustration. He seized the scroll again and pointed to his eyes. Did he mean that I should read the scroll, or did he point to his tears? I bit my lip and turned up my palms, unable to help him.

Eco threw the scroll in my lap and ran crying from the room. A hoarse, stifled braying issued from his throat, not the sound of normal weeping; it tore my heart to hear it. I should have been more patient, but how was I to understand him? Bethesda emerged from the kitchen and gazed at me accusingly, then followed the sound of Eco's weeping to the little room where he slept.

I looked down at the scroll in my lap. There were so many words on the parchment; which ones had keyed an idea in Eco's memory, and what could they have to do with dead Panurgus? Red, green, blue-I vaguely remembered reading a passage in which Plato discoursed on the nature of light and color, but I could scarcely remember it, not having understood much of it in the first place. Some scheme about overlapping cones projected from the eyes to an object, or from the object to the eyes, I couldn't remember which; was this what Eco recalled, and could it have made any sense to him?

I rolled through the scroll, looking for the reference, but was unable to find it. My eyes grew weary. The lamp began to sputter. The Greek letters all began to look alike. Normally Bethesda would have come to put me to bed, but it seemed she had chosen to comfort Eco instead. I fell asleep on my dining couch beneath the stars, thinking of a yellow cloak stained with red, and of lifeless green eyes gazing at an empty blue sky.

Eco was ill the next day, or feigned illness. Bethesda solemnly informed me that he did not wish to leave his bed. I stood in the doorway of his little room and spoke to him gently, reminding him that the Roman Festival continued, and that today there would be a wild beast show in the Circus Maximus, and another play put on by another company. He turned his back to me and pulled the coverlet over his head.

"I suppose I should punish him," I whispered to myself, trying to think of what a normal Roman father would do.

"I suppose you should not," whispered Bethesda as she passed me. Her haughtiness left me properly humbled.

I took my morning stroll alone-for the first time in many days, I realized, acutely aware that Eco was not beside me. The Subura seemed a rather dull place without ten-year-old eyes through which to see it. I had only my own eyes to serve me, and they had seen it a million times before.

I would buy him a gift, I decided; I would buy them each a gift, for it was always a good idea to placate Bethesda when she was haughty. For Eco I bought a red leather ball, such as boys use to play trigon, knocking it back and forth to each other using their elbows and knees. For Bethesda I wanted to find a veil woven of blue midnight shot through with silver moths, but I decided to settle for one made of linen. On the street of the cloth merchants I found the shop of my old acquaintance Ruso.

I asked to see a veil of dark blue. As if by magic he produced the very veil I had been imagining, a gossamer thing that seemed to be made of blue-black spiderwebs and silver. It was also most expensive item in the shop. I chided him for taunting me with a luxury beyond my means.

Ruso shrugged good-naturedly. "One never knows; might have just been playing dice, and won a fortune by casting the Venus Throw. Here, these are more affordable." He smiled and laid a selection before me.

"No," I said, seeing nothing I liked, "I've changed my mind."

"Then something in a lighter blue, perhaps.? A bright blue, like the sky."

"No, I think not-"

"Ah, but see what I have to show you first. Felix… Felix! Fetch me one of the new veils that just arrived from Alexandria, the bright blue ones with yellow stitching."

The young slave bit his lip nervously and seemed to cringe. This struck me as odd, for I knew Ruso to be a temperate man and not a cruel master.

"Go on, then-what are you waiting for.?" Ruso turned to me and shook his head. "This new slave-worse than useless! I don't think he's very smart, no matter what the slave merchant said. He keeps the books well enough, but here in the shop- look, he's done it again! Unbelievable! Felix, what is wrong with you? Do you do this just to spite me? Do you want a beating? I won't put up with this any longer, I tell you!"

The slave shrank back, looking confused and helpless. In his hand he held a yellow veil.

"All the time he does this!" wailed Ruso, clutching his head.

"He wants to drive me mad! I ask for blue and he brings me yellow! I ask for yellow and he brings me blue! Have you ever heard of such stupidity? I shall beat you, Felix, I swear it!" He ran after the poor slave, brandishing a measuring rod. And then I understood.

My friend Statilius, as I had expected, was not at his lodgings in the Subura. When I questioned his landlord, the old man gave me the sly look of a confederate charged with throwing hounds off the scent, and told me that Statilius had left Rome for the countryside.

He was in none of the usual places where he might have been on a festival day. No tavern had served him and no brothel had admitted him. He would not even think of appearing in a gambling house, I told myself-and then knew that the exact opposite must be true.

Once I began to search the gaming places in the Subura, I found him easily enough. In a crowded apartment on the third floor of an old tenement I discovered him in the midst of a crowd of well-dressed men, some of them even wearing their togas. Statilius was down on his elbows and knees, shaking a tiny box and muttering prayers to Fortune. He cast the dice; the crowd contracted in a tight circle and then drew back, exclaiming. The throw was a good one: III, III, III and VI-the Remus Throw.

"Yes! Yes!" Statilius cried, and held out his palms. The others handed over their coins.

I grabbed him by the collar of his tunic and pulled him squawking into the hall.

"I should think you're deeply enough in debt already," I said.

"Quite the contrary!" he protested, smiling broadly. His face was flushed and his forehead beaded with sweat, like a man with a fever.

"Just how much do you owe Flavius the moneylender?"

"A hundred thousand sesterces."

"A hundred thousand!" My heart leaped into my throat.

"But not any longer. You see, I'll be able to pay him of now!" He held up the coins in his hands. "I have two bags full of silver in the other room, where my slave's looking after them. And-can you believe it?-a deed to a house on the Caelian Hill. I've won my way out of it, don't you see?"

"At the expense of another man's life."

His grin became sheepish. "So, you've figured that out. But who could have foreseen such a tragedy? Certainly not I. And when it happened, I didn't rejoice in Panurgus's death-you saw that. I didn't hate him, not really. My jealousy was purely professional. But if the Fates decided better him than me, who am I to argue?"

"You're a worm, Statilius. Why didn't you tell Roscius what you knew? Why didn't you tell me?"

"What did I know, really? Someone completely unknown might have killed poor Panurgus. I didn't witness the event."

"But you guessed the truth, all the same. That's why you wanted me backstage, wasn't it? You were afraid the assassin would come back for you. What was I, your bodyguard?"

"Perhaps. After all, he didn't come back, did he?"

"Statilius, you're a worm."

"You said that already." The smile dropped from his face like a discarded mask. He jerked his collar from my grasp.

"You hid the truth from me," I said, "but why from Roscius?"

"What, tell him I had run up an obscene gambling debt and had a notorious moneylender threatening to kill me?"

"Perhaps he'd have loaned you the money to pay off the debt." '

"Never! You don't know Roscius. He thinks I'm lucky just to be in his troupe; believe me, he's not the type to hand out loans to an underling in the amount of a hundred thousand sesterces.

And if he knew Panurgus had mistakenly been murdered instead of me-oh, Roscius would have been furious! One Panurgus is worth ten Statilii, that's his view. I would have been a dead man then, with Flavius on one side of me and Roscius on the other. The two of them would have torn me apart like a chicken bone!" He stepped back and straightened his tunic. The smile flickered and returned to his lips. "You're not going to tell anyone, are you?"

"Statilius, do you ever stop acting?" I averted my eyes to avoid his charm.

"Well?"

"Roscius is my client, not you."

"But I'm your friend, Gordianus."

"I made a promise to Panurgus."

"Panurgus didn't hear you."

"The gods did."

Finding the moneylender Flavius was a simpler matter-a few questions in the right ear, a few coins in the right hands. I learned that he ran his business from a wine shop in a portico near the Circus Flaminius, where he sold inferior vintages imported from his native Tarquinu. But on a festival day, my informants told me, I would be more likely to find him at the house of questionable repute across the street.

The place had a low ceiling and the musty smell of spilled wine and crowded humanity. Across the room I saw Flavius, holding court with a group of his peers-businessmen of middle age with crude country manners, dressed in expensive tunics and cloaks of a quality that contrasted sharply with their wearers' crudeness.

Closer at hand, leaning against a wall (and looking strong enough to hold it up), was the moneylender's bully. The blond giant was looking rather drunk, or else exceptionally stupid. He slowly blinked when I approached. A glimmer of recognition lit his bleary eyes and then faded.

"Festival days are good drinking days," I said, raising my cup of wine. He looked at me without expression for a moment, then shrugged and nodded.

"Tell me," I said, "do you know any of those spectacular beauties.?" I gestured to a group of four women who loitered at the far corner of the room, near the foot of the stairs.

The giant shook his head glumly.

"Then you are a lucky man this day." I leaned close enough to smell the wine on his breath. "I was just talking to one of them. She tells me that she longs to meet you. It seems she has an appetite for men with sunny hair and big shoulders. She tells me that for a man such as you…" I whispered in his ear.

The veil of lust across his face made him look even stupider. He squinted drunkenly. "Which one?" he asked in a husky whisper.

"The one in the blue gown," I said.

"Ah…" He nodded and burped, then pushed past me and stumbled toward the stairs. As I had expected, he ignored the woman in green, as well as the woman in coral and the one in brown. Instead he placed his hand squarely upon the hip of the woman in yellow, who turned and looked up at him with a surprised but not unfriendly gaze.

"Quintus Roscius and his partner Chaerea were both duly impressed by my cleverness," I explained later that night to Bethesda. I was unable to resist the theatrical gesture of swinging the little bag of silver up in the air and onto the table, where it landed with a jingling thump. "Not a pot of gold, perhaps, but a fat enough fee to keep us all happy through the winter."

Her eyes became as round and glittering as little coins.

They grew even larger when I produced the veil from Ruso's shop.

"Oh! But what is it made of?"

"Midnight and moths," I said. "Spiderwebs and silver." She tilted her head back and spread the translucent veil over her naked throat and arms. I blinked and swallowed hard, and decided that the purchase was well worth the price.

Eco stood uncertainly in the doorway of his little room, where he had watched me enter and had listened to my hurried tale of the day's events. He seemed to have recovered from his distemper of the morning, but his face was somber. I held out my hand, and he cautiously approached. He took the red leather ball readily enough, but he still did not smile.

"Only a small gift, I know. But I have a greater one for you…"

"Still, I don't understand," protested Bethesda. "You've said the blond giant was stupid, but how can anyone be so stupid as to not be able to tell one color from another?"

"Eco knows," I said, smiling ruefully down at him. "He figured it out last night and tried to tell me, but he didn't know how. He remembered a passage from Plato that I read to him months ago; I had forgotten all about it. Here, I think I can find it now." I reached for the scroll, which still lay upon my sleeping couch.

" 'One may observe,'" I read aloud," 'that not all men perceive the same colors. Although they are rare, there are those who confuse the colors red and green, and likewise those who cannot tell yellow from blue; still others appear to have no perception of the various shades of green.' He goes on to offer an explanation of this, but I cannot follow it."

"Then the bodyguard could not tell blue from yellow?" said Bethesda. "Even so…"

"The moneylender came to the theater yesterday intending to make good on his threat to murder Statilius. No wonder Flavius gave a start when I leaned over and said, 'Today you'll see The Pot of Gold'-for a moment he thought I was talking about the debt Statilius owed him! He sat in the audience long enough to see that Statilius was playing Megadorus, dressed in blue; no doubt he could recognize him by his voice. Then he sent the blond assassin backstage, knowing the alley behind the Temple of Jupiter would be virtually deserted, there to lie in wait for the actor in the blue cloak. Eco must have overheard snatches of his instructions, if only the word blue. He sensed that something was amiss even then, and tried to tell me at the time, but there was too much confusion, with the giant stepping on my toes and the audience howling around us. Am I right?"

Eco nodded, and slapped a fist against his palm: exactly right.

"Unfortunately for poor Panurgus in his yellow cloak, the color-blind assassin was also uncommonly stupid. He needed more information than the color blue to make sure he murdered the right man, but he didn't bother to ask for it; or if he did, Flavius would only have sneered at him and rushed him along, unable to understand his confusion. Catching Panurgus alone and vulnerable in his yellow cloak, which might as well have been blue, the assassin did his job-and bungled it.

"Knowing Flavius was in the audience and out to kill him, learning that Panurgus had been stabbed, and seeing that the hired assassin was no longer in the audience, Statilius guessed the truth; no wonder he was so shaken by Panurgus's death, knowing that he was the intended victim."

"So another slave is murdered, and by accident! And nothing will be done," Bethesda said moodily.

"Not exactly. Panurgus was valuable property. The law allows his owners to sue the man responsible for his death for his full market value. I understand that Roscius and Chaerea are Is each demanding one hundred thousand sesterces from Flavius. If Flavius contests the action and loses, the amount will be doubled. Knowing his greed, I suspect he'll tacitly admit his guilt and settle for the smaller figure."

"Small justice for a meaningless murder."

I nodded. "And small recompense for the destruction of so much talent. But such is the only justice that Roman law allows, when a citizen kills a slave."

A heavy silence descended on the garden. His insight vindicated, Eco turned his attention to the leather ball. He tossed it in the air, caught it, and nodded thoughtfully, pleased at the way it fit his hand.

"Ah, but Eco, as I was saying, there is another gift for you." He looked at me expectantly. "It's here." I patted the sack of silver. "No longer shall I teach you in my own stumbling way how to read and write. You shall have a proper tutor, who will come every morning to teach you both Latin and Greek. He will be stern, and you will suffer, but when he is done you will read and write better than I do. A boy as clever as you deserves no less."

Eco's smile was radiant. I have never seen a boy toss a ball so high.

The story is almost done, except for one final outcome.

Much later that night, I lay in bed with Bethesda with nothing to separate us but that gossamer veil shot through with silver threads. For a few fleeting moments I was completely satisfied with life and the universe. In my relaxation, without meaning to, I mumbled aloud what I was thinking. "Perhaps I should adopt the boy…"

"And why not?" Bethesda demanded, imperious even when half asleep. "What more proof do you want from him? Eco could not be more like your son even if he were made of your own flesh and blood."

And of course she was right.

(support [a t] reallib.org)