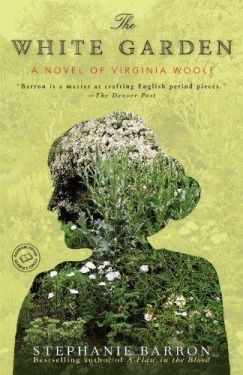

"The White Garden: A Novel of Virginia Woolf" - читать интересную книгу автора (Баррон Стефани)

|

28 March 1941 PROLOGUE

IT WAS CHILLIER THAN SHE EXPECTED THAT MORNING, and a stiff wind shuddered through the apple blossoms — penetrating even to the desk in the Lodge at Rodmell, where she preferred to write. The wind formed a background to her stuttering thoughts, not unlike the sound of airplane engines cutting out overhead — there had been so many engines in recent months that she’d stood beneath them as they passed, her bony fists clamped to her jutting hips, staring upwards from the back garden. So many planes. So many bombs, that one had actually fallen near the house when she wasn’t looking. The river dykes were smashed and the water crept over the flat Sussex meadows as steadily as infantry.

She had hoarded poison against the coming Germans and made death pacts — she would not be taken alive. But by winter the planes had dwindled, predatory birds bound for harsher climes. Leonard hid the poison very secretly while she was in London one day.

And so she was forced to make other plans.

She wrapped the wings of the ancient cardigan closer about her wasted frame and began to write.

He never used the word

The book was called

Leonard was at his most brisk during such periods. He would leave his work in the garden or the typeface he laboriously set on the hand printing press and shepherd her towards a chair, offer the bulk of her knitting, employ the hands that no longer held a pen. He would urge endless glasses of milk down her throat and forbid visitors. Keep her from travelling to London — although it was the bombs that had taken London from her now, the house in Tavistock Square cratered to its foundations. Leonard wanted the best for her; Leonard manufactured peace.

Squandering their rationed petrol, he had driven her across the countryside to Brighton yesterday, so that Octavia might look at her.

The horror of unbuttoning her blouse before the woman doctor; the ugliness of her rib cage; the sag of nearly sixty years. She had answered Octavia’s piercing questions in monosyllables.

Now she signed her farewell and put down her pen. She did not look back as she left the Lodge in the garden.

LATER, IN HER FUR COAT AND GALOSHES, HER WALKING stick in one hand, she traversed the drowned meadows to the river.

A bird was perched on a fence-post, not ten feet away, trilling despite the bombs:

Even as a child, she had dreamed ecstatically of drowning. Water had an inexorable pull: at the sight of it, she was dizzy with longing and vertigo. To stand on the bank of the River Ouse was to grip the edge of a volcano: she could hardly keep from hurling herself in. The current was nothing, close to the edge; a few days before, when she had ventured out, the ripples quickened at her knees, then sucked at her thighs, a lover dragging her to a sticky bed. Then she’d surrendered to it, sinking down until an unexpected claustrophobia overwhelmed her — the water slamming on her head like a cupboard door. She fought her way out, arms flailing and feet stumbling, her skirts dragging her back.

She told Leonard she’d slipped into a dyke. A bit of weed twined around one leg.

If she were to try again, she thought, it would be important to find some stones.

She picked up a few beauties as she trolled along the riverbank. A chunk of granite; a sharp slate knife. The bird sang past her as the water eddied in the stiff breeze.

In Latin, the word would be

(support [a t] reallib.org)