"The Corrections" - читать интересную книгу автора (Franzen Jonathan)

AT SEA

TWO HUNDRED HOURS, darkness, the

As things pitched, so they trembled. There was a shivering in the

He lay approximately awake in Stateroom B11. Awake in a metal box that pitched and trembled, a dark metal box moving somewhere in the night.

There was no porthole. A room with a view would have cost hundreds of dollars more, and Enid had reasoned that since a stateroom was mainly used for sleeping who needed a porthole, at that price? She might look through it six times on the voyage. That was fifty dollars a look.

She was sleeping now, silently, like a person feigning sleep. Alfred asleep was a symphony of snoring and whistling and choking, an epic of Z’s. Enid was a haiku. She lay still for hours and then blinked awake like a light switched on. Sometimes at dawn in St. Jude, in the long minute it took the clock-radio to flip a digit, the only moving thing in the house was the eye of Enid.

On the morning of Chip’s conception she’d merely looked like she was shamming sleep, but on the morning of Denise’s, seven years later, she really was pretending. Alfred in middle age had invited such venial deceptions. A decade-plus of marriage had turned him into one of the overly civilized predators you hear about in zoos, the Bengal tiger that forgets how to kill, the lion lazy with depression. To exert attraction, Enid had to be a still, unbloody carcass. If she actively reached out, actively threw a thigh over his, he braced himself against her and withheld his face; if she so much as stepped from the bathroom naked he averted his eyes, as the Golden Rule enjoined the man who hated to be seen himself. Only early in the morning, waking to the sight of her small white shoulder, did he venture from his lair. Her stillness and self-containment, the slow sips of air she took, her purely vulnerable object-hood, made him pounce. And feeling his padded paw on her ribs and his meat-seeking breath on her neck she went limp, as if with prey’s instinctive resignation (“Let’s get this dying over with”), although in truth her passivity was calculated, because she knew passivity inflamed him. He had her, and to some extent she wanted to be had, like an animal: in a mute mutual privacy of violence. She, too, kept her eyes shut. Often didn’t even roll from the side she’d been lying on but simply flared her hip, brought her knee up in a vaguely proctologic reflex. Then without showing her his face he departed for the bathroom, where he washed and shaved and emerged to see the bed already made and to hear, downstairs, the percolator gulping. From Enid’s perspective in the kitchen maybe a lion, not her husband, had voluptuously mauled her, or maybe one of the men in uniform she ought to have married had slipped into her bed. It wasn’t a wonderful life, but a woman could subsist on self-deceptions like these and on her memories (which also now curiously seemed like self-deceptions) of the early years when he’d been mad for her and had looked into her eyes. The important thing was to keep it all tacit. If the act was never spoken of, there would be no reason to discontinue it until she was definitely pregnant again, and even after pregnancy no reason not to resume it, as long as it was never mentioned.

She’d always wanted three children. The longer nature denied her a third, the less fulfilled she felt in comparison to her neighbors. Bea Meisner, though fatter and dumber than Enid, publicly smooched with her husband, Chuck; twice a month the Meisners hired a sitter and went dancing. Every October without fail Dale Driblett took his wife, Honey, someplace extravagant and out of state for their anniversary, and the many young Dribletts all had birthdays in July. Even Esther and Kirby Root could be seen at barbecues patting each other’s well-marbled bottoms. It frightened and shamed Enid, the loving-kindness of other couples. She was a bright girl with good business skills who had gone directly from ironing sheets and tablecloths at her mother’s boardinghowse to ironing sheets and shirts chez Lambert. In every neighbor woman’s eyes she saw the tacit question: Did Al at least make her feel super-special in that special way?

As soon as she was visibly pregnant again, she had a tacit answer. The changes in her body were incontrovertible, and she imagined so vividly the flattering inferences about her love life that Bea and Esther and Honey might draw from these changes that soon enough she drew the inferences herself.

Made happy in this way by pregnancy, she got sloppy and talked about the wrong thing to Alfred. Not, needless to say, about sex or fulfillment or fairness. But there were other topics scarcely less forbidden, and Enid in her giddiness one morning overstepped. She suggested he buy shares of a certain stock. Alfred said the stock market was a lot of dangerous nonsense best left to wealthy men and idle speculators. Enid suggested he nonetheless buy shares of a certain stock. Alfred said he remembered Black Tuesday as if it were yesterday. Enid suggested he nonetheless buy shares of a certain stock. Alfred said it would be highly improper to buy that stock. Enid suggested he nonetheless buy it. Alfred said they had no money to spare and now a third child coming. Enid suggested that money could be borrowed. Alfred said no. He said no in a much louder voice and stood up from the breakfast table. He said no so loudly that a decorative copper-plate bowl on the kitchen wall briefly hummed, and without kissing her goodbye he left the house for eleven days and ten nights.

Who would have guessed that such a little mistake on her part could change everything?

In August the Midland Pacific had made Alfred its assistant chief engineer for track and structures, and now he’d been sent east to inspect every mile of the Erie Belt Railroad. Erie Belt district managers shuttled him around in dinky gas-powered motor cars, darting in bug fashion onto sidings while Erie Belt megalosaurs thundered past. The Erie Belt was a regional system whose freight business trucks had damaged and whose passenger business private automobiles had driven into the red. Although its trunk lines were still generally hale, its branches and spurs were rotting like you couldn’t believe. Trains poked along at 10 mph on rails no straighter than limp string. Mile upon mile of hopelessly buckled Belt. Alfred saw crossties better suited to mulching than to gripping spikes. Rail anchors that had lost their heads to rust, bodies wasting inside a crust of corrosion like shrimps in a shell of deep-fry. Ballast so badly washed out that ties were hanging from the rail rather than supporting it. Girders peeling and corrupted like German chocolate cake, the dark shavings, the miscellaneous crumble.

How modest—compared to the furious locomotive—a stretch of weedy track could seem, skirting a field of late sorghum. But without this track a train was ten thousand tons of ungovernable nothing. The will was in the track.

Everywhere Alfred went in the Erie Belt’s hinterland he heard young Erie Belt employees telling one another, “Take it easy!”

“See ya later, Sam. Don’t work too hard, now.”

“Take it easy.”

“You too, pal. Take it easy.”

The phrase seemed to Alfred an eastern blight, a fitting epitaph for a once-great state, Ohio, that parasitic Teamsters had sucked nearly dry. Nobody in St. Jude would dare tell

The Midland Pacific, by contrast, was clean steel and white concrete. Crossties so new that blue creosote pooled in their grain. The applied science of vibratory tamping and prestressed rebar, motion detectors and welded rail. The Midpac was based in St. Jude and served a harder-working, less eastern region of the country. Unlike the Erie Belt, it took pride in its commitment to maintaining quality service on its branch lines. A thousand towns and small cities across the central tiers of states depended on the Midpac.

The more Alfred saw of the Erie Belt, the more distinctly he felt the Midland Pacific’s superior size, strength, and moral vitality in his own limbs and carriage. In his shirt and tie and wing tips he nimbly took the catwalk over the Maumee River, forty feet above slag barges and turbid water, grabbed the truss’s lower chord and leaned out upside down to whack the span’s principal girder with his favorite whacking hammer, which he carried everywhere in his briefcase; scabs of paint and rust as big as sycamore leaves spiraled down into the river. A yard engine ringing its bell crept onto the span, and Alfred, who had no fear of heights, leaned into a hanger brace and planted his feet in the matchstick ties sticking out over the river. While the ties waggled and jumped he jotted on his clipboard a damning assessment of the bridge’s competence.

Maybe some of the women drivers crossing the Maumee on the neighboring Cherry Street bridge saw him perched there, flat of belly and broad of shoulder, the wind winding his cuffs around his ankles, and maybe they felt, as Enid had felt the first time she’d laid eyes on him, that here was a

Nighttime was a different matter. By night he lay awake on mattresses that felt made of cardboard and catalogued the faults of humanity. It seemed as if, in every motel he stayed in, he had neighbors who fornicated like there was no tomorrow—men of ill-breeding and poor discipline, women who chuckled and screamed. At 1 a. m. in Erie, Pennsylvania, a girl in the next room ranted and panted like a strumpet. Some slick, worthless fellow having his way with her. Alfred blamed the girl for taking it easy. He blamed the man for his easygoing confidence. He blamed both of them for lacking the consideration to keep their voices down. How could they never once stop to think of their neighbor, lying awake in the next room? He blamed God for allowing such people to exist. He blamed democracy for inflicting them on him. He blamed the motel’s architect for trusting a single layer of cinder block to preserve the repose of paying customers. He blamed the motel management for not keeping in reserve a room for guests who suffered. He blamed the frivolous, easygoing townspeople of Washington, Pennsylvania, who had driven 150 miles for a high-school football championship game and filled every motel room in northwest Pennsylvania. He blamed his fellow guests for their indifference to the fornication, he blamed all of humanity for its insensitivity, and it was so unfair. It was unfair that the world could be so inconsiderate to a man who was so considerate to the world. No man worked harder than he, no man made a quieter motel neighbor, no man was more of a man, and yet the phonies of the world were allowed to rob him of sleep with their lewd transactions …

He refused to weep. He believed that if he heard himself weeping, at two in the morning in a smoke-smelling motel room, the world might end. If nothing else, he had discipline. The power to refuse: he had this.

But his exercising of it went unthanked. The bed in the next room thudded against the wall, the man groaning like a ham, the girl gasping in her ululations. And every waitress in every town had spherical mammaries insufficiently buttoned into a monogrcmmed blouse and made a point of leaning over him.

“More coffee, good-lookin’?”

“Ah, yes, please.”

“You blushin’, sweetheart, or is that the sun comin’ up?”

“I will take the check now, thank you.”

And in the Olmsted Hotel in Cleveland he surprised a porter and a maid lasciviously osculating in a stairwell. And the tracks he saw when he closed his eyes were a zipper that he endlessly unzipped, and the signals behind him turned from forbidding red to willing green the instant he passed them, and in a saggy bed in Fort Wayne awful succubuses descended on him, women whose entire bodies—their very clothes and smiles, the crossings of their legs—exuded invitation like vaginas, and up to the surface of his consciousness (do not soil the bed!) he raced the welling embolus of spunk, his eyes opening to Fort Wayne at sunrise as a scalding nothing drained into his pajamas: a victory, all things considered, for he’d denied the succubuses his satisfaction. But in Buffalo the trainmaster had a pinup of Brigitte Bardot on his office door, and in Youngstown Alfred found a filthy magazine beneath the motel telephone book, and in Hammond, Indiana, he was trapped on a siding while a freight train slid past him and varsity cheerleaders did splits on the ball field directly to his left, the blondest girl actually bouncing a little at the very bottom of her split, as if she had to kiss the cleat-chewed sod with her cotton-clad vulva, and the caboose rocking saucily as the train finally receded up the tracks: how the world seemed bent on torturing a man of virtue.

He returned to St. Jude in an executive car appended to an intercity freight run, and from Union Station he took the commuter local to the suburbs. In the blocks between the station and his house the last leaves were coming down. It was the season of hurtling, hurtling toward winter. Cavalries of leaf wheeled across the bitten lawns. He stopped in the street and looked at the house that he and a bank owned. The gutters were plugged with twigs and acorns, the mum beds were blasted. It occurred to him that his wife was pregnant again. Months were rushing him forward on their rigid track, carrying him closer to the day he’d be the father of three, the year he’d pay off his mortgage, the season of his death.

“I like your suitcase,” Chuck Meisner said through the window of his commuter Fairlane, braking in the street alongside him. “For a second I thought you were the Fuller Brush man.”

“Chuck,” said Alfred, startled. “Hello.”

“Planning a conquest. The husband’s out of town forever.”

Alfred laughed because there was nothing else for it. He and Chuck met in the street often, the engineer standing at attention, the banker relaxing at the wheel. Alfred in a suit and Chuck in golfwear. Alfred lean and flattopped. Chuck shiny-pated, saggy-breasted. Chuck worked easy hours at the branch he managed, but Alfred nonetheless considered him a friend. Chuck actually listened to what he said, seemed impressed with the work he did, and recognized him as a person of singular abilities.

“Saw Enid in church on Sunday,” Chuck said. “She told me you’d been gone a week already.”

“Eleven days I was on the road.”

“Emergency somewhere?”

“Not exactly.” Alfred spoke with pride. “I was inspecting every mile of track on the Erie Belt Railroad.”

“Erie Belt. Huh.” Chuck hooked his thumbs over the steering wheel, resting his hands on his lap. He was the most easygoing driver Alfred knew, yet also the most alert. “You do your job well, Al,” he said. “You’re a fantastic engineer. So there’s got to be a reason why the Erie Belt.”

“There is indeed,” Alfred said. “Midpac’s buying it.”

The Fairlane’s engine sneezed once in a canine way. Chuck had grown up on a farm near Cedar Rapids, and the optimism of his nature was rooted in the deep, well-watered topsoil of eastern Iowa. Farmers in eastern Iowa never learned not to trust the world. Whereas any soil that might have nurtured hope in Alfred had blown away in one or another west Kansan drought.

“So,” Chuck said. “I imagine there’s been a public announcement.”

“No. No announcement.”

Chuck nodded, looking past Alfred at the Lambert house. “Enid’ll be happy to see you. I think she’s had a hard week. The boys have been sick.”

“You’ll keep that information quiet.”

“Al, Al, Al.”

“I wouldn’t mention it to anyone but you.”

“Appreciate it. You’re a good friend and a good Christian. And I’ve got about four holes’ worth of daylight if I’m going to get that hedge pruned back.”

The Fairlane inched into motion, Chuck steering it into his driveway with one index finger, as if dialing his broker.

Alfred picked up his suitcase and briefcase. It had been both spontaneous and the opposite of spontaneous, his disclosure. A spasm of goodwill and gratitude to Chuck, a calculated emission of the fury that had been building inside him for eleven days. A man travels two thousand miles but he can’t take the last twenty steps without doing something—

And it did seem unlikely that Chuck would actually use the information—

Entering the house through the kitchen door, Alfred saw chunks of raw rutabaga in a pot of water, a rubber-banded bunch of beet greens, and some mystery meat in brown butcher paper. Also a casual onion that looked destined to be fried and served with—liver?

On the floor by the basement stairs was a nest of magazines and jelly glasses.

“Al?” Enid called from the basement.

He set down his suitcase and briefcase, gathered the magazines and jelly glasses in his arms, and carried them down the steps.

Enid parked her iron on the ironing board and emerged from the laundry room with butterflies in her stomach—whether from lust or from fear of Al’s rage or from fear that she might become enraged herself she didn’t know.

He set her straight in a hurry. “What did I ask you to do before I left?”

“You’re home early,” she said. “The boys are still at the Y.”

“What is the one thing I asked you to do while I was gone?”

“I’m catching up on laundry. The boys have been sick.”

“Do you remember,” he said, “that I asked you to take care of the mess at the top of the stairs? That that was the one thing—the one thing—I asked you to do while I was gone?”

Without waiting for an answer, he went into his metallurgy lab and dumped the magazines and jelly glasses into a heavy-duty trash can. From the hammer shelf he took a badly balanced hammer, a crudely forged Neanderthal club that he hated and kept only for purposes of demolition, and methodically broke each jelly glass. A splinter hit his cheek and he swung more furiously, smashing the shards into smaller shards, but nothing could eradicate his transgression with Chuck Meisner, or the grass-damp triangles of cheerleading leotard, no matter how he hammered.

Enid listened from her station at the ironing board. She didn’t care much for the reality of this moment. That her husband had left town eleven days ago without kissing her goodbye was a thing she’d halfway succeeded in forgetting. With the living Al absent, she’d alchemically transmuted her base resentments into the gold of longing and remorse. Her swelling womb, the pleasures of the fourth month, the time alone with her handsome boys, the envy of her neighbors all were colorful philtres over which she’d waved the wand of her imagination. Even as Al had come down the stairs she’d still imagined apologies, homecoming kisses, a bouquet of flowers maybe. Now she heard the ricochet of broken glass and glancing hammer blows on heavy-gauge galvanized iron, the frustrated shrieks of hard materials in conflict. The philtres may have been colorful but unfortunately (she saw now) they were chemically inert. Nothing had really changed.

It was true that Al had asked her to move the jars and magazines, and there was probably a word for the way she’d stepped around those jars and magazines for the last eleven days, often nearly stumbling on them; maybe a psychiatric word with many syllables or maybe a simple word like “spite.” But it seemed to her that he’d asked her to do more than “one thing” while he was gone. He’d also asked her to make the boys three meals a day, and clothe them and read to them and nurse them in sickness, and scrub the kitchen floor and wash the sheets and iron his shirts, and do it all without a husband’s kisses or kind words. If she tried to get credit for these labors of hers, however, Al simply asked her whose labors had paid for the house and food and linens? Never mind that his work so satisfied him that he didn’t need her love, while her chores so bored her that she needed his love doubly. In any rational accounting, his work canceled her work.

Perhaps, in strict fairness, since he’d asked her to do “one thing” extra, she might have asked him to do “one thing” extra, too. She might have asked him to telephone her once from the road, for example. But he could argue that “someone’s going to trip on those magazines and hurt themselves,” whereas no one was going to trip over his not calling her from the road, no one was going to hurt themselves over that. And charging long-distance calls to the company was an abuse of his expense account (“You have my office number if there’s an emergency”), and so a phone call cost the household quite a bit of money, whereas carrying junk into the basement cost it no money, and so she was always wrong, and it was demoralizing to dwell perpetually in the cellar of your wrongness, to wait perpetually for someone to take pity on you in your wrongness, and so it was no wonder, really, that she’d shopped for the

Halfway up the basement stairs, on her way to preparing this dinner, she paused and gave a sigh.

Alfred heard the sigh and suspected it had to do with “laundry” and “four months pregnant.” However,

From the front door of the house came a thumping of little feet and a mittened knocking, Bea Meisner dropping off her human cargo. Enid hurried on up the stairs to accept delivery. Gary and Chipper, her fifth-grader and her first-grader, had the chlorination of the Y about them. With their damp hair they looked riparian. Muskratty, beaverish. She called thanks to Bea’s taillights.

As fast as they could without running (forbidden indoors), the boys proceeded to the basement, dropped their logs of sodden terry cloth in the laundry room, and found their father in his laboratory. It was in their nature to throw their arms around him, but this nature had been corrected out of them. They stood and waited, like company subordinates, for the boss to speak.

“So!” he said. “You’ve been swimming.”

“I’m a Dolphin!” Gary cried. He was an unaccountably cheerful boy. “I got my Dolphin clip!”

“A Dolphin. Well, well.” To Chipper, to whom life had offered mainly tragic perspectives since he was about two years old, the boss more gently said: “You, lad?”

“We used kickboards,” Chipper said.

“He’s a Tadpole,” Gary said.

“So. A Dolphin and a Tadpole. And what special skills do you bring to the workplace now that you’re a Dolphin?”

“Scissors kick.”

“I wish I’d had a nice big swimming pool like that when I was growing up,” the boss said, although for all he knew the pool at the Y was neither nice nor big. “Except for some muddy water in a cow pond I don’t recall seeing water deeper than three feet until I saw the Platte River. I must have been nearly ten.”

His youthful subordinates weren’t following. They shifted on their feet, Gary still smiling tentatively as though hopeful of an upturn in the conversation, Chipper frankly gaping at the laboratory, which was forbidden territory except when the boss was in it. The air here tasted like steel wool.

Alfred regarded his two subordinates gravely. Fraternizing had always been a struggle for him. “Have you been helping your mother in the kitchen?” he said.

When a subject didn’t interest Chipper, as this one didn’t, he thought about girls, and when he thought about girls he felt a surge of hope. On the wings of this hope he floated from the laboratory and up the stairs.

“Ask me nine times twenty-three,” Gary told the boss.

“All right,” Alfred said. “What is nine times twenty-three?”

“Two hundred seven. Ask me another.”

“What’s twenty-three squared?”

In the kitchen Enid dredged the Promethean meat in flour and laid it in a Westinghouse electric pan large enough to fry nine eggs in ticktacktoe formation. A cast aluminum lid clattered as the rutabaga water came abruptly to a boil. Earlier in the day a half package of bacon in the refrigerator had suggested liver to her, the drab liver had suggested a complement of bright yellow, and so the Dinner had taken shape. Unfortunately, when she went to cook the bacon she discovered there were only three strips, not the six or eight she’d imagined. She was now struggling to believe that three strips would suffice for the entire family.

“What’s that?” said Chipper with alarm.

“Liver ’n’ bacon!”

Chipper backed out of the kitchen shaking his head in violent denial. Some days were ghastly from the outset; the breakfast oatmeal was studded with chunks of date like chopped-up cockroach; bluish swirls of inhomogeneity in his milk; a doctor’s appointment after breakfast. Other days, like this one, did not reveal their full ghastliness till they were nearly over.

He reeled through the house repeating: “Ugh, horrible, ugh, horrible, ugh, horrible, ugh, horrible …”

“Dinner in five minutes, wash your hands,” Enid called.

Cauterized liver had the odor of fingers that had handled dirty coins.

Chipper came to rest in the living room and pressed his face against the window, hoping for a glimpse of Cindy Meisner in her dining room. He had sat next to Cindy returning from the Y and smelled the chlorine on her. A sodden Band-Aid had clung by a few lingering bits of stickum to her knee.

Thukkety thukkety thukkety went Enid’s masher round the pot of sweet, bitter, watery rutabaga.

Alfred washed his hands in the bathroom, gave the soap to Gary, and employed a small towel.

“Picture a square,” he said to Gary.

Enid knew that Alfred hated liver, but the meat was full of health-bringing iron, and whatever Alfred’s shortcomings as a husband, no one could say he didn’t play by the rules. The kitchen was her domain, and he never meddled.

“Chipper, have you washed your hands?”

It seemed to Chipper that if he could only see Cindy again for one moment he might be rescued from the Dinner. He imagined being with her in her house and following her to her room. He imagined her room as a haven from danger and responsibility.

“Chipper?”

“You square A, you square B, and you add twice the product of A and B,” Alfred told Gary as they sat down at the table.

“Chipper, you better wash your hands,” Gary warned.

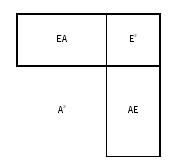

Alfred pictured a square:

|

“I’m sorry I’m a little short on bacon,” Enid said. “I thought I had more.”

In the bathroom Chipper was reluctant to wet his hands because he was afraid he would never get them dry again. He let the water run audibly while he rubbed his hands with a towel. His failure to glimpse Cindy through the window had wrecked his composure.

“We had high fevers,” Gary reported. “Chipper had an earache, too.”

Brown grease-soaked flakes of flour were impastoed on the ferrous lobes of liver like corrosion. The bacon also, what little there was of it, had the color of rust.

Chipper trembled in the bathroom doorway. You encountered a misery near the end of the day and it took a while to gauge its full extent. Some miseries had sharp curvature and could be negotiated readily. Others had almost no curvature and you knew you’d be spending hours turning the corner. Great whopping-big planet-sized miseries. The Dinner of Revenge was one of these.

“How was your trip,” Enid asked Alfred because she had to sometime.

“Tiring.”

“Chipper, sweetie, we’re all sitting down.”

“I’m counting to five,” Alfred said.

“There’s bacon, you like bacon,” Enid sang. This was a cynical, expedient fraud, one of her hundred daily conscious failures as a mother.

“Two, three, four,” Alfred said.

Chipper ran to take his place at the table. No point in getting spanked.

“Blessalor this foodier use nusta thy service make asair mindful neesa others Jesus name amen,” Gary said.

A dollop of mashed rutabaga at rest on a plate expressed a clear yellowish liquid similar to plasma or the matter in a blister. Boiled beet greens leaked something cupric, greenish. Capillary action and the thirsty crust of flour drew both liquids under the liver. When the liver was lifted, a faint suction could be heard. The sodden lower crust was unspeakable.

Chipper considered the life of a girl. To go through life softly, to be a Meisner, to play in that house and be loved like a girl.

“You want to see my jail I made with Popsicle sticks?” Gary said.

“A jail, well well,” Alfred said.

The provident young person neither ate his bacon immediately nor let it be soaked by the vegetable juices. The provident young person evacuated his bacon to the higher ground at the plate’s edge and stored it there as an incentive. The provident young person ate his bite of fried onions, which weren’t good but also weren’t bad, if he needed a preliminary treat.

“We had a den meeting yesterday,” Enid said. “Gary, honey, we can look at your jail after dinner.”

“He made an electric chair,” Chipper said. “To go in his jail. I helped.”

“Ah? Well well.”

“Mom got these huge boxes of Popsicle sticks,” Gary said.

“It’s the Pack,” Enid said. “The Pack gets a discount.”

Alfred didn’t think much of the Pack. A bunch of fathers taking it easy ran the Pack. Pack-sponsored activities were lightweight: contests involving airplanes of balsa, or cars of pinewood, or trains of paper whose boxcars were books read.

(Schopenhauer: If you want a safe compass to guide you through life … you cannot do better than accustom yourself to regard this world as a penitentiary, a sort of penal colony.)

“Gary, say again what you are,” said Chipper, for whom Gary was the glass of fashion. “Are you a Wolf?”

“One more Achievement and I’m a Bear.”

“What are you now, though, a Wolf ?”

“I’m a Wolf but basically I’m a Bear. All’s I have to do now is Conversation.”

“Conservation,” Enid corrected. “All I have to do now is Conservation.”

“It’s not Conversation?”

“Steve Driblett made a gillateen but it didn’t work,” Chipper said.

“Driblett’s a Wolf.”

“Brent Person made a plane but it busted in half.”

“Person is a Bear.”

“Say broke, sweetie, not busted.”

“Gary, what’s the biggest firecracker?” Chipper said.

“M-80. Then cherry bombs.”

“Wouldn’t it be neat to get an M-80 and put it in your jail and blow it up?”

“Lad,” Alfred said, “I don’t see you eating your dinner.”

Chipper was growing emceeishly expansive; for the moment, the Dinner had no reality. “Or seven M-80s,” he said, “and you blew ’em all at once, or one after another, wouldn’t it be neat?”

“I’d put a charge in every corner and then put extra fuse,” Gary said. “I’d wind the fuses together and detonate them all at once. That’s the best way to do it, isn’t it, Dad. Separate the charges and put an extra fuse, isn’t it. Dad?”

“Seven thousand hundred million M-80s,” Chipper cried. He made explosive noises to suggest the megatonnage he had in mind.

“Chipper,” Enid said with smooth deflection, “tell Dad where we’re all going next week.”

“The den’s going to the Museum of Transport and I get to come, too,” Chipper recited.

“Oh Enid.” Alfred made a sour face. “What are you taking them there for?”

“Bea says it’s very interesting and fun for kids.”

Alfred shook his head, disgusted. “What does Bea Meisner know about transportation?”

“It’s perfect for a den meeting,” Enid said. “There’s a real steam engine the boys can sit in.”

“What they have,” Alfred said, “is a thirty-year-old Mohawk from the New York Central. It’s not an antique. It’s not rare. It’s a piece of junk. If the boys want to see what a real railroad is—”

“Put a battery and two electrodes on the electric chair,” Gary said.

“Put an M-80!”

“Chipper, no, you run a current and the current kills the prisoner.”

“What’s a current?”

A current flowed when you stuck electrodes of zinc and copper in a lemon and connected them.

What a sour world Alfred lived in. When he caught himself in mirrors it shocked him how young he still looked. The set of mouth of hemorrhoidal schoolteachers, the bitter permanent lip-pursing of arthritic men, he could taste these expressions in his own mouth sometimes, though he was physically in his prime, the souring of life.

He did therefore enjoy a rich dessert. Pecan pie. Apple brown Betty. A little sweetness in the world.

“They have two locomotives and a real caboose!” Enid said.

Alfred believed that the real and the true were a minority that the world was bent on exterminating. It galled him that romantics like Enid could not distinguish the false from the authentic: a poor-quality, flimsily stocked, profit-making “museum” from a real, honest railroad—

“You have to at least be a Fish.”

“The boys are all excited.”

“I could be a Fish.”

The Mohawk that was the new museum’s pride was evidently a romantic symbol. People nowadays seemed to resent the railroads for abandoning romantic steam power in favor of diesel. People didn’t understand the first goddamned thing about running a railroad. A diesel locomotive was versatile, efficient, and low-maintenance. People thought the railroad owed them romantic favors, and then they bellyached if a train was slow. That was the way most people were—stupid.

(Schopenhauer: Amongst the evils of a penal colony is the company of those imprisoned in it.)

At the same time, Alfred himself hated to see the old steam engine pass into oblivion. It was a beautiful iron horse, and by putting the Mohawk on display the museum allowed the easygoing leisure-seekers of suburban St. Jude to dance on its grave. City people had no right to patronize the iron horse. They didn’t know it intimately, as Alfred did. They hadn’t fallen in love with it out in the northwest corner of Kansas where it was the only link to the greater world, as Alfred had. He despised the museum and its goers for everything they didn’t know.

“They have a model railroad that takes up a whole room!” Enid said relentlessly.

And the goddamned model railroaders, yes, the goddamned hobbyists. Enid knew perfectly well how he felt about these dilettantes and their pointless and implausible model layouts.

“A whole room?” Gary said with skepticism. “How big?”

“Wouldn’t it be neat to put some M-80s on, um, on, um, on a model railroad bridge? Ker-PERSSSCHT! P’kow, p’kow!”

“Chipper, eat your dinner now,” Alfred said.

“Big big big,” Enid said. “The model is much much much much much bigger than the one your father bought you.”

“Now,” Alfred said. “Are you listening to me? Now.”

Two sides of the square table were happy and two were not. Gary told a pointless, genial story about this kid in his class who had three rabbits while Chipper and Alfred, twin studies in bleakness, lowered their eyes to their plates. Enid visited the kitchen for more rutabaga.

“I know who not to ask if they want seconds,” she said when she returned.

Alfred shot her a warning look. They had agreed for the sake of the boys’ welfare never to allude to his own dislike of vegetables and certain meats.

“I’ll take some,” Gary said.

Chipper had a lump in his throat, a desolation so obstructive that he couldn’t have swallowed much in any case. But when he saw his brother happily devouring seconds of Revenge, he became angry and for a moment understood how his entire dinner might be scarfable in no time, his duties discharged and his freedom regained, and he actually picked up his fork and made a pass at the craggy wad of rutabaga, tangling a morsel of it in his tines and bringing it near his mouth. But the rutabaga smelled carious and was already cold—it had the texture and temperature of wet dog crap on a cool morning—and his guts convulsed in a spine-bending gag reflex.

“I love rutabaga,” said Gary inconceivably.

“I could live on nothing but vegetables,” Enid averred.

“More milk,” Chipper said, breathing hard.

“Chipper, just hold your nose if you don’t like it,” Gary said.

Alfred put bite after bite of vile Revenge in his mouth, chewing quickly and swallowing mechanically, telling himself he had endured worse than this.

“Chip,” he said, “take one bite of each thing. You’re not leaving this table till you do.”

“More milk.”

“You will eat some dinner first. Do you understand?”

“Milk.”

“Does it count if he holds his nose?” Gary said.

“More milk, please.”

“That is just about enough,” Alfred said.

Chipper fell silent. His eyes went around and around his plate, but he had not been provident and there was nothing on the plate but woe. He raised his glass and silently urged a very small drop of warm milk down the slope to his mouth. He stretched his tongue out to welcome it.

“Chip, put the glass down.”

“Maybe he could hold his nose but then he has to eat two bites of things.”

“There’s the phone. Gary, you may answer it.”

“What’s for dessert?” Chipper said.

“I have some nice fresh pineapple.”

“Oh for God’s sake, Enid—”

“What?” She blinked innocently or faux-innocently.

“You can at least give him a cookie, or an Eskimo Pie, if he eats his dinner—”

“It’s such sweet pineapple. It melts in your mouth.”

“Dad, it’s Mr. Meisner.”

Alfred leaned over Chipper’s plate and in a single action of fork removed all but one bite of the rutabaga. He loved this boy, and he put the cold, poisonous mash into his own mouth and jerked it down his throat with a shudder. “Eat that last bite,” he said, “take one bite of the other, and you can have dessert.” He stood up. “I will buy the dessert if necessary.”

As he passed Enid on his way to the kitchen, she flinched and leaned away.

“Yes,” he said into the phone.

Through the receiver came the humidity and household clutter, the warmth and fuzziness, of Meisnerdom.

“Al,” Chuck said, “just looking in the paper here, you know, Erie Belt stock, uh. Five and five-eighths seems awfully low. You sure about this Midpac thing?”

“Mr. Replogle rode the motor car with me out of Cleveland. He indicated that the Board of Managers is simply waiting for a final report on track and structures. I’m going to give them that report on Monday.”

“Midpac’s kept this very quiet.”

“Chuck, I can’t recommend any particular course of action, and you’re right, there are some unanswered questions here—”

“Al, Al,” Chuck said. “You have a mighty conscience, and we all appreciate that. I’ll let you get back to your dinner.”

Alfred hung up hating Chuck as he would have hated a girl he’d been undisciplined enough to have relations with. Chuck was a banker and a thriver. You wanted to spend your innocence on someone worthy of it, and who better than a good neighbor, but no one could be worthy of it. There was excrement all over his hands.

“Gary: pineapple?” Enid said.

“Yes, please!”

The virtual disappearance of Chipper’s root vegetable had made him a tad manic. Things were l-l-l-looking up! He expertly paved one quadrant of his plate with the remaining bite of rutabaga, grading the yellow asphalt with his fork. Why dwell in the nasty reality of liver and beet greens when there was constructable a future in which your father had gobbled these up, too? Bring on the cookies! sayeth Chipper. Bring on the Eskimo Pie!

Enid carried three empty plates into the kitchen.

Alfred, by the phone, was studying the clock above the sink. The time was that malignant fiveishness to which the flu sufferer awakens after late-afternoon fever dreams. A time shortly after five which was a mockery of five. To the face of clocks the relief of order—two hands pointing squarely at whole numbers—came only once an hour. As every other moment failed to square, so every moment held the potential for fluish misery.

And to suffer like this for no reason. To know there was no moral order in the flu, no justice in the juices of pain his brain produced. The world nothing but a materialization of blind, eternal Will.

(Schopenhauer: No little part of the torment of existence is that Time is continually pressing upon us, never letting us catch our breath but always coming after us, like a taskmaster with a whip.)

“I guess you don’t want pineapple,” Enid said. “I guess you’re buying your own dessert.”

“Enid, drop it. I wish once in your life you would let something drop.”

Cradling the pineapple, she asked why Chuck had called.

“We will talk about it later,” Alfred said, returning to the dining room.

“Daddy?” Chipper began.

“Lad, I just did you a favor. Now you do me a favor and stop playing with your food and finish your dinner. Right now. Do you understand me? You will finish it right now, or there will be no dessert and no other privileges tonight or tomorrow night, and you will sit here until you do finish it.”

“Daddy, though, can you—?”

“RIGHT NOW. DO YOU UNDERSTAND ME, OR DO YOU NEED A SPANKING?”

Tonsils release an ammoniac mucus when serious tears gather behind them. Chipper’s mouth twisted this way and that. He saw the plate in front of him in a new light. It was as if the food were an unbearable companion whose company he had been sure that his connections higher up, the strings pullable on his behalf, would spare him. Now came the realization that he and the food were in it for the long haul.

Now he mourned the passing of his bacon, paltry though it had been, with a deep and true grief.

Curiously, though, he didn’t outright cry.

Alfred retired to the basement with stamping and a slam.

Gary sat very quietly multiplying small whole numbers in his head.

Enid plunged a knife into the pineapple’s jaundiced belly. She decided that Chipper was exactly like his father—at once hungry and impossible to feed. He turned food into shame. To prepare a square meal and then to see it greeted with elaborate disgust, to see the boy actually gag on his breakfast oatmeal: this stuck in a mother’s craw. All Chipper wanted was milk and cookies, milk and cookies. Pediatrician said: “Don’t give in. He’ll get hungry eventually and eat something else.” So Enid tried to be patient, but Chipper sat down to lunch and declared: “This smells like vomit!” You could slap his wrist for saying it, but then he said it with his face, and you could spank him for making faces, but then he said it with his eyes, and there were limits to correction—no way, in the end, to penetrate behind the blue irises and eradicate a boy’s disgust.

Lately she had taken to feeding him grilled cheese sandwiches all day long, holding back for dinner the yellow and leafy green vegetables required for a balanced diet and letting Alfred fight her battles.

There was something almost tasty and almost sexy in letting the annoying boy be punished by her husband. In standing blamelessly aside while the boy suffered for having hurt her.

What you discovered about yourself in raising children wasn’t always agreeable or attractive.

She carried two dishes of pineapple into the dining room. Chipper’s head was bowed, but the son who loved to eat reached eagerly for his dish.

Gary slurped and aerated, wordlessly consuming pineapple.

The dogshit-yellow field of rutabaga; the liver warped by frying and so unable to lie flush with the plate; the ball of woody beet leaves collapsed and contorted but still entire, like a wetly compressed bird in an eggshell, or an ancient corpse folded over in a bog: the spatial relations among these foods no longer seemed to Chipper haphazard but were approaching permanence, finality.

The foods receded, or a new melancholy shadowed them. Chipper became less immediately disgusted; he ceased even to think about eating. Deeper sources of refusal were kicking in.

Soon the table was cleared of everything but his place mat and his plate. The light grew harsher. He heard Gary and his mother conversing on trivial topics as she washed and Gary dried. Then Gary’s footsteps on the basement stairs. Metronomic thock of Ping-Pong ball. More desolate peals of large pots being handled and submerged.

His mother reappeared. “Chipper, just eat that up. Be a big boy now.”

He had arrived in a place where she couldn’t touch him. He felt nearly cheerful, all head, no emotion. Even his butt was numb from pressing on the chair.

“Dad means for you to sit there till you eat that. Finish it up now. Then your whole evening’s free.”

If his evening had been truly free he might have spent it entirely at a window watching Cindy Meisner.

“Noun adjective,” his mother said, “contraction possessive noun. Conjunction conjunction stressed pronoun counterfactual verb pronoun I’d just gobble that up and temporal adverb pronoun conditional auxiliary infinitive—”

Peculiar how unconstrained he felt to understand the words that were spoken to him. Peculiar his sense of freedom from even that minimal burden of decoding spoken English.

She tormented him no further but went to the basement, where Alfred had shut himself inside his lab and Gary was amassing (“Thirty-seven, thirty-eight”) consecutive bounces on his paddle.

“Tock tock?” she said, wagging her head in invitation.

She was hampered by pregnancy or at least the idea of it, and Gary could have trounced her, but her pleasure at being played with was so extremely evident that he simply disengaged himself, mentally multiplying their scores or setting himself small challenges like returning the ball to alternating quadrants. Every night after dinner he honed this skill of enduring a dull thing that brought a parent plgasure. It seemed to him a lifesaving skill. He believed that terrible harm would come to him when he could no longer preserve his mother’s illusions.

And she looked so vulnerable tonight. The exertions of dinner and dishes had relaxed her hair’s rollered curls. Little blotches of sweat were blooming through the cotton bodice of her dress. Her hands had been in latex gloves and were as red as tongues.

He sliced a winner down the line and past her, the ball running all the way to the shut door of the metallurgy lab. It bounced up and knocked on this door before subsiding. Enid pursued it carefully. What silence, what darkness, there was behind that door. Al seemed not to have a light on.

There existed foods that even Gary hated—Brussels sprouts, boiled okra—and Chipper had watched his pragmatic sibling palm them and fling them into dense shrubbery from the back doorway, if it was summer, or secrete them on his person and dump them in the toilet, if it was winter. Now that Chipper was alone on the first floor he could easily have disappeared his liver and his beet greens. The difficulty: his father would think that he had eaten them, and eating them was exactly what he was refusing now to do. Food on the plate was necessary to prove refusal.

He minutely peeled and scraped the flour crust off the top of the liver and ate it. This took ten minutes. The denuded surface of the liver was a thing you didn’t want to see.

He unfolded the beet greens somewhat and rearranged them.

He examined the weave of the place mat.

He listened to the bouncing ball, his mother’s exaggerated groans and her nerve-grating cries of encouragement (“Ooo, good one, Gary!”). Worse than spanking or even liver was the sound of someone else’s Ping-Pong. Only silence was acceptable in its potential to be endless. The score in Ping-Pong bounced along toward twenty-one and then the game was over, and then two games were over, and then three were over, and to the people inside the game this was all right because fun had been had, but to the boy at the table upstairs it was not all right. He’d involved himself in the sounds of the game, investing them with hope to the extent of wishing they might never stop. But they did stop, and he was still at the table, only it was half an hour later. The evening devouring itself in futility. Even at the age of seven Chipper intuited that this feeling of futility would be a fixture of his life. A dull waiting and then a broken promise, a panicked realization of how late it was.

This futility had let’s call it a flavor.

After he scratched his head or rubbed his nose his fingers harbored something. The smell of self.

Or again, the taste of incipient tears.

Imagine the olfactory nerves sampling themselves, receptors registering their own configuration.

The taste of self-inflicted suffering, of an evening trashed in spite, brought curious satisfactions. Other people stopped being real enough to carry blame for how you felt. Only you and your refusal remained. And like self-pity, or like the blood that filled your mouth when a tooth was pulled—the salty ferric juices that you swallowed and allowed yourself to savor—refusal had a flavor for which a taste could be acquired.

In the lab below the dining room Alfred sat with his head bowed in the darkness and his eyes closed. Interesting how eager he’d been to be alone, how hatefully clear he’d made this to everyone around him; and now, having finally closeted himself, he sat hoping that someone would come and disturb him. He wanted this someone to see how much he hurt. Though he was cold to her it seemed unfair that she was cold in turn to him: unfair that she could happily play Ping-Pong, shuffle around outside his door, and never knock and ask how he was doing.

Three common measures of a material’s strength were its resistance to pressure, to tension, and to shearing.

Every time his wife’s footsteps approached the lab he braced himself to accept her comforts. Then he heard the game ending, and he thought surely she would take pity on him now. It was the one thing he asked of her, the one thing—

(Schopenhauer: Woman pays the debt of life not by what she does, but by what she suffers; by the pains of childbearing and care for the child, and by submission to her husband, to whom she should be a patient and cheering companion.)

But no rescue was forthcoming. Through the closed door he heard her retreat to the laundry room. He heard the mild buzz of a transformer, Gary playing with the O-gauge train beneath the Ping-Pong table.

A fourth measure of strength, important to manufacturers of rail stock and machine parts, was hardness.

With unspeakable expenditure of will Alfred turned on a light and opened his lab notebook.

Even the most extreme boredom had merciful limits. The dinner table, for example, possessed an underside that Chipper explored by resting his chin on the surface and stretching his arms out below. At his farthest reach were baffles pierced by taut wire leading to pullable rings. Complicated intersections of roughly finished blocks and angles were punctuated, here and there, by deeply countersunk screws, little cylindrical wells with scratchy turnings of wood fiber around their mouths, irresistible to the probing finger. Even more rewarding were the patches of booger he’d left behind during previous vigils. The dried patches had the texture of rice paper or fly wings. They were agreeably dislodgable and pulverizable.

The longer Chipper felt his little kingdom of the underside, the more reluctant he became to lay eyes on it. Instinctively he knew that the visible reality would be puny. He’d see crannies he hadn’t yet discovered with his fingers, and the mystery of the realms beyond his reach would be dispelled, the screw holes would lose their abstract sensuality and the boogers would shame him, and one evening, then, with nothing left to relish or discover, he just might die of boredom.

Elective ignorance was a great survival skill, perhaps the greatest.

Enid’s alchemical lab beneath the kitchen contained a Maytag with a wringer that swung over it, twinned rubber rollers like enormous black lips. Bleach, bluing, distilled water, starch. A bulky locomotive of an iron, its power cord clad in a patterned knit fabric. Mounds of white shirts in three sizes.

To prepare a shirt for pressing she sprinkled it with water and left it rolled up in a towel. When it was thoroughly redampened she ironed the collar first and then the shoulders, working down.

During and after the Depression she’d learned many survival skills. Her mother ran a boardinghouse in the basin between downtown St. Jude and the university. Enid had a gift for math, and so she not only washed sheets and cleaned toilets and served meals but also handled numbers for her mother. By the time she’d finished high school and the war had ended, she was keeping all the house’s books, billing the boarders, and figuring the taxes. With the quarters and dollars she picked up on the side—wages from baby-sitting, tips from college boys and other long-term boarders—she paid for classes at night school, inching toward a degree in accounting which she hoped she would never have to use. Already two men in uniform had proposed to her, each of them a rather good dancer, but neither was clearly an earner and both still risked getting shot at. Her mother had married a man who didn’t earn and died young. Avoiding such a husband was a priority with Enid. She intended to be comfortable in life as well as happy.

To the boardinghouse a few years after the war came a young steel engineer newly transferred to St. Jude to manage a foundry. He was a full-lipped thick-haired well-muscled boy in a man’s shape and a man’s suits. The suits were themselves luxuriantly pleated wool beauties. Once or twice every night, serving dinner at the big round table, Enid glanced over her shoulder and caught him looking, and made him blush. Al was Kansan. After two months he found courage to take her skating. They drank cocoa and he told her that human beings were born to suffer. He took her to a steel-company Christmas party and told her that the intelligent were doomed to be tormented by the stupid. He was a good dancer and a good earner, however, and she kissed him in the elevator. Soon they were engaged and they chastely rode a night train to McCook, Nebraska, to visit his aged parents. His father kept a slave whom he was married to.

Cleaning Al’s room in St. Jude she found a much-handled volume of Schopenhauer with certain passages underlined. For example: The pleasure in this world, it has been said, outweighs the pain; or, at any rate, there is an even balance between the two. If the reader wishes to see shortly whether this statement is true, let him compare the respective feelings of two animals, one of which is engaged in eating the other.

What to believe about Al Lambert? There were the old-man things he said about himself and the young-man way he looked. Enid had chosen to believe the promise of his looks. Life then became a matter of waiting for his personality to change.

While she waited, she ironed twenty shirts a week, plus her own skirts and blouses.

Nosed in around the buttons with the iron’s tip. Flattened the wrinkles, worked out the kinks.

Her life would have been easier if she hadn’t loved him so much, but she couldn’t help loving him. Just to look at him was to love him.

Every day she endeavored to cleanse the boys’ diction, smooth out their manners, whiten their morals, brighten their attitudes, and every day she faced another pile of dirty crumpled laundry.

Even Gary was anarchic sometimes. He liked best to send the electric-engine barreling into curves and derail it, see the black chunk of metal skid awkwardly and roll and spark in frustration. Second best was to place plastic cows and cars on the rail and engineer little tragedies.

What gave him the real techno boner, however, was a radio-controlled toy automobile, much advertised on television lately, that went anywhere. To avoid ambiguity he planned to make it the only item on his Christmas list.

From the street, if you paid attention, you could see the light in the windows dimming as Gary’s train or Enid’s iron or Alfred’s experiments drained power off the grid. But how lifeless the house looked otherwise. In the lighted houses of the Meisners, of the Schumperts and the Persons and the Roots, people were clearly at home—whole families grouped around tables, young heads bent over homework, dens aflicker with TV, toddlers careening, a grandparent testing a tea bag’s virtue with a third soaking. These were spirited, unselfconscious houses.

Whether anybody was home meant everything to a house. It was more than a major fact: it was the only fact.

The family was the house’s soul.

The waking mind was like the light in a house.

The soul was like the gopher in his hole.

Consciousness was to brain as family was to house.

Aristotle: Suppose the eye were an animal—sight would be its soul.

To understand the mind you pictured domestic activity, the hum of related lives on varied tracks, the hearth’s fundamental glow. You spoke of “presence” and “clutter” and “occupation.” Or, conversely, of “vacancy” and “shutting down.” Of “disturbance.”

Maybe the futile light in a house with three people separately absorbed in the basement and only one upstairs, a little boy staring at a plate of cold food, was like the mind of a depressed person.

Gary was the first to tire of the basement. He surfaced and skirted the too-bright dining room, as if it held the victim of a sickening disfigurement, and went up to the second floor to brush his teeth.

Enid followed soon with seven warm white shirts. She, too, skirted the dining room. She reasoned that if the problem in the dining room was her responsibility then she was horrendously derelict in not resolving it, and a loving mother could never be so derelict, and she was a loving mother, so the responsibility must not have been hers. Eventually Alfred would surface and see what a beast he’d been and be very, very sorry. If he had the nerve to blame her for the problem, she could say: “You’re the one who said he had to sit there till he ate it.”

While she ran a bath she tucked Gary into bed. “Always be my little lion,” she said.

“OK.”

“Is he fewocious? Is he wicious? Is he my wicious wittle wion?”

Gary didn’t answer these questions. “Mom,” he said. “Chipper is still at the table, and it’s almost nine.”

“That’s between Dad and Chipper.”

“Mom? He really doesn’t like those foods. He’s not just pretending.”

“I’m so glad you’re a good eater,” Enid said.

“Mom, it’s not really fair.”

“Sweetie, this is a phase your brother’s going through. It’s wonderful you’re so concerned, though. It’s wonderful to be so loving. Always be so loving.”

She hurried to stop the water and immerse herself.

In a dark bedroom next door Chuck Meisner imagined, going inside her, that Bea was Enid. As he chugged to ejaculation he was trading.

He wondered if any exchange had a market in Erie Belt options. Buy five thousand shares outright with thirty puts for a downside hedge. Or better, if someone offered him a rate, a hundred naked calls.

She was pregnant and trading up in cup size, A to B and eventually even C, Chuck guessed, by the time the baby came. Like some municipality’s bond rating in a tailspin.

One by one the lights of St. Jude were going out.

And if you sat at the dinner table long enough, whether in punishment or in refusal or simply in boredom, you never stopped sitting there. Some part of you sat there all your life.

As if sustained and too-direct contact with time’s raw passage could scar the nerves permanently, like staring at the sun.

As if too-intimate knowledge of any interior were necessarily harmful knowledge. Were knowledge that could never be washed off.

(How weary, how worn, a house lived in to excess.)

Chipper heard things and saw things but they were all in his head. After three hours, the objects surrounding him were as drained of flavor as old bubble gum. His mental states were strong by comparison and overwhelmed them. It would have taken an effort of will, a reawakening, to summon the term “place mat” and apply it to the visual field that he had observed so intensely that its reality had dissolved in the observing, or to apply the word “furnace” to the rustle in the ducts which in its recurrence had assumed the character of an emotional state or an actor in his imagination, an embodiment of Evil Time. The faint fluctuations in the light as someone ironed and someone played and someone experimented and the refrigerator cycled on and off had been part of the dream. This changefulness, though barely noticeable, had been a torment. But it had stopped now.

Now only Alfred remained in the basement. He probed a gel of ferroacetates with the electrodes of an ammeter.

A late frontier in metallurgy: custom-formation of metals at room temperature. The Grail was a substance which could be poured or molded but which after treatment (perhaps with an electrical current) had steel’s superior strength and conductivity and resistance to fatigue. A substance easy like plastic and hard like metal.

The problem was urgent. A cultural war was being waged, and the forces of plastic were winning. Alfred had seen jam and jelly jars with plastic lids. Cars with plastic roofs.

Unfortunately, metal in its free state—a nice steel stake or a solid brass candlestick—represented a high level of order, and Nature was slatternly and preferred disorder. The crumble of rust. The promiscuity of molecules in solution. The chaos of warm things. States of disorder were vastly more likely to arise spontaneously than were cubes of perfect iron. According to the Second Law of Thermodynamics, much work was required to resist this tyranny of the probable—to force the atoms of a metal to behave themselves.

Alfred was sure that electricity was equal to this work. The current that came through the grid amounted to a borrowing of order from a distance. At power plants an organized piece of coal became a flatulence of useless warm gases; an elevated and self-possessed reservoir of water became entropic runoff wandering toward a delta. Such sacrifices of order produced the useful segregation of electrical charges that he put to work at home.

He was seeking a material that could, in effect, electroplate itself. He was growing crystals in unusual materials in the presence of electric currents.

It wasn’t hard science but the brute probabilism of trial and error, a groping for accidents that he might profit from. One college classmate of his had already made his first million with the results of a chance discovery.

That he might someday not have to worry about money: it was a dream identical to the dream of being comforted by a woman, truly comforted, when the misery overcame him.

The dream of radical transformation: of one day waking up and finding himself a wholly different (more confident, more serene) kind of person, of escaping that prison of the given, of feeling divinely capable.

He had clays and gels of silicate. He had silicone putties. He had slushy ferric salts succumbing to their own deliquescence. Ambivalent acetylacetonates and tetracarbonyls with low melting points. A chunk of gallium the size of a damson plum.

The head chemist at the Midland Pacific, a Swiss Ph.D. bored into melancholy by a million measurements of engine-oil viscosity and Brinell hardness, kept Alfred in supplies. Their superiors were aware of the arrangement—Alfred would never have risked getting caught in something underhanded—and it was informally understood that if he ever came up with a patentable process, the Midpac would get a share of any proceeds.

Tonight something unusual was happening in the ferroacetate gel. His conductivity readings varied wildly, depending on where exactly he stuck the ammeter’s probe. Thinking the probe might be dirty, he switched to a narrow needle with which he again poked the gel. He got a reading of no conductivity at all. Then he stuck the gel in a different place and got a high reading.

What was going on?

The question absorbed and comforted him and held the taskmaster at bay until, at ten o’clock, he extinguished the microscope’s illuminator and wrote in his notebook: STAIN BLUE CHROMATE 2%. VERY VERY INTERESTING.

The moment he stepped from the lab, exhaustion hammered him. He fumbled to secure the lock, his analytic fingers suddenly thick and stupid. He had boundless energy for work, but as soon as he quit he could barely stand up.

His exhaustion deepened when he went upstairs. The kitchen and dining room were ablaze in light, and there appeared to be a small boy slumped over the dining-room table, his face on his place mat. The scene was so wrong, so sick with Revenge, that for a moment Alfred honestly thought the boy at the table was a ghost from his own childhood.

He groped for switches as if the light were a poison gas he had to stop the flow of.

In less hazardous dimness he gathered the boy in his arms and carried him upstairs. The boy had the weave of the place mat engraved on one cheek. He murmured nonsense. He was half-awake but resisting full consciousness, keeping his head down as Alfred undressed him and found pajamas in the closet.

Once the boy was in bed, in receipt of a kiss and fast asleep, an unguessable amount of time trickled through the legs of the bedside chair in which Alfred sat conscious of little but the misery between his temples. His tiredness hurt so much it kept him awake.

Or maybe he did sleep, for suddenly he was standing up and feeling marginally refreshed. He left Chipper’s room and went to check on Gary.

Just inside Gary’s door, reeking of Elmer’s glue, was a jail of Popsiclesticks. The jail bore no relation to the elaborate house of correction that Alfred had imagined. It was a crude roofless square, crudely bisected. Its floor plan, in fact, was exactly the binomial square he’d evoked before dinner.

And this, this here in the jail’s largest room, this bollixed knot of semisoft glue and broken Popsicle sticks was a—doll’s wheelbarrow? Miniature step stool?

Electric chair.

In a mind-altering haze of exhaustion Alfred knelt and examined it. He found himself susceptible to the poignancy of the chair’s having been made—to the pathos of Gary’s impulse to fashion an object and seek his father’s approval—and more disturbingly to the impossibility of squaring this crude object with the precise mental picture of an electric chair that he had formed at the dinner table. Like an illogical woman in a dream who was both Enid and not Enid, the chair he’d pictured had been at once completely an electric chair and completely Popsicle sticks. It came to him now, more forcefully than ever, that maybe every “real” thing in the world was as shabbily protean, underneath, as this electric chair. Maybe his mind was even now doing to the seemingly real hardwood floor on which he knelt exactly what it had done, hours earlier, to the unseen chair. Maybe a floor became truly a floor only in his mental reconstruction of it. The floor’s nature was to some extent inarguable, of course; the wood definitely existed and had measurable properties. But there was a second floor, the floor as mirrored in his head, and he worried that the beleaguered “reality” that he championed was not the reality of an actual floor in a actual bedroom but the reality of a floor in his head which was idealized and no more worthy, therefore, than one of Enid’s silly fantasies.

The suspicion that everything was relative. That the “real” and “authentic” might not be simply doomed but fictive to begin with. That his feeling of righteousness, of uniquely championing the real, was just a feeling. These were the suspicions that had lain in ambush in all those motel rooms. These were the deep terrors beneath the flimsy beds.

And if the world refused to square with his version of reality then it was necessarily an uncaring world, a sour and sickening world, a penal colony, and he was doomed to be violently lonely in it.

He bowed his head at the thought of how much strength a man would need to survive an entire life so lonely.

He returned the pitiful, unbalanced electric chair to the floor of the prison’s largest room. As soon as he let go of the chair, it fell on its side. Images of hammering the jail to bits passed through his head, flashes of hiked-up skirts and torn-down underpants, images of shredded bras and outthrust hips, but came to nothing.

Gary was sleeping in perfect silence, the way his mother did. There was no hope that he’d forgotten his father’s implicit promise to look at the jail after dinner. Gary never forgot anything.

Still, I am doing my best, Alfred thought.

Returning to the dining room, he noticed the change in the food on Chipper’s plate. The well-browned margins of the liver had been carefully pared off and eaten, as had every scrap of crust. There was evidence as well that rutabaga had been swallowed; the small speck that remained was scored with tiny tine marks. And several beet greens had been dissected, the softer leaves removed and eaten, the woody reddish stems laid aside. It appeared that Chipper had taken the contractual one bite of each food after all, presumably at great personal cost, and had been put to bed without being given the dessert he’d earned.

On a November morning thirty-five years earlier Alfred had found a coyote’s bloody foreleg in the teeth of a steel trap, evidence of certain desperate hours in the previous night.

There came an upwelling of pain so intense that he had to clench his jaw and refer to his philosophy to prevent its turning into tears.

(Schopenhauer: Only one consideration may serve to explain the sufferings of animals: that the will to live, which underlies the entire world of phenomena, must in their case satisfy its cravings by feeding upon itself.)

He turned off the last lights downstairs, visited the bathroom, and put on fresh pajamas. He had to open his suitcase to retrieve his toothbrush.

Into the bed, the museum of antique transports, he slipped beside Enid, settling as close to the far edge as he could. She was asleep in her sleep-feigning way. He looked once at the alarm clock, the radium jewelry on its two pointing hands—closer to twelve now than to eleven—and shut his eyes.

Came the question in a voice like noon: “What were you talking about with Chuck?”

His exhaustion redoubled. With his closed eyes he saw beakers and probes and the trembling needle of the ammeter.

“It sounded like the Erie Belt,” Enid said. “Does Chuck know about that? Did you tell him?”

“Enid, I am very tired.”

“I’m just surprised, that’s all. Considering.”

“It was an accident and I regret it.”

“I just think it’s interesting,” Enid said, “that Chuck is allowed to make an investment that we’re not allowed to make.”

“If Chuck chooses to take unfair advantage of other investors, that’s his business.”

“A lot of Erie Belt shareholders would be happy to get five and three-quarters tomorrow. What’s unfair about that?”

Her words had the sound of an argument rehearsed for hours, a grievance nursed in darkness.

“Those shares will be worth nine and a half dollars three weeks from now,” Alfred said. “I know it and most people don’t. That’s unfair.”

“You’re smarter than other people,” Enid said, “and you did better in school, and now you have a better job. That’s unfair, too, isn’t it? Shouldn’t you make yourself stupid, to be completely fair?”

Chewing your own leg off was not an act to be undertaken lightly or performed halfway. At what point and by what process did the coyote make the decision to sink its teeth into its own flesh? Presumably there first came a period of waiting and weighing. But after that?

“I’m not going to argue with you,” Alfred said. “Since you are awake, however, I want to know why Chip wasn’t put to bed.”

“You were the one who said he—”

“You came upstairs long before I did. It was not my intention that he sit there for five hours. You’re using him against me, and I don’t care for it one bit. He should have been put to bed at eight.”

Enid simmered in her wrongness.

“Can we agree that this will not happen again?” Alfred said.

“We can agree.”

“Well then. Let’s sleep.”

When it was very, very dark in the house, the unborn child could see as clearly as anyone. She had ears and eyes, fingers and a forebrain and a cerebellum, and she floated in a central place. She already knew the main hungers. Day after day the mother walked around in a stew of desire and guilt, and now the object of the mother’s desire lay three feet away from her. Everything in the mother was poised to melt and shut down at a loving touch anywhere on her body.

There was a lot of breathing going on. A lot of breathing but no touching.

Sleep eluded even Alfred. Each sinusy gasp of Enid’s seemed to pierce his ear the instant he was poised afresh to drop off.

After an interval that he judged to have lasted twenty minutes, the bed began to shake with poorly reined sobs.

He broke his silence, almost wailing: “What is it now?”

“Nothing.”

“Enid, it is very, very late, and the alarm is set for six, and I am bone-weary.”

She wept stormily. “You never kissed me goodbye!”

“I’m aware of that.”

“Well, don’t I have a right? A husband leaves his wife at home alone for two weeks?”

“This is water under the bridge. And frankly I’ve endured a lot worse.”

“And then he comes home and doesn’t even say hello? He just attacks me?”

“Enid, I have had a terrible week.”

“And leaves the dinner table before dinner’s over?”

“A terrible week and I am extraordinarily tired—”

“And locks himself in the basement for five hours? Even though he’s supposedly very tired?”

“If you had had the week I had—”

“You didn’t kiss me goodbye.”

“Grow up! For God’s sake! Grow up!”

“Keep your voice down!”

(Keep your voice down or the baby might hear.)

(Indeed did hear and was soaking up every word.)

“Do you think I was on a pleasure cruise?” Alfred demanded in a whisper. “Everything I do I do for you and the boys. It’s been two weeks since I had a minute to myself. I believe I’m entitled to a few hours in the laboratory. You would not understand it, and you would not believe me if you did, but I have found something very interesting.”

“Oh, very interesting,” Enid said. Hardly the first time she’d heard this.

“Well it is very interesting.”

“Something with commercial applications?”

“You never know. Look what happened to Jack Callahan. This could end up paying for the boys’ education.”

“I thought you said Jack Callahan’s discovery was an accident.”

“My God, listen to yourself. You tell me I’m negative, but when it’s work that matters to me, who’s negative?”

“I just don’t understand why you won’t even consider—”

“Enough.”

“If the object is to make money—”

“Enough. Enough! I don’t give a damn what other people do. I am not that kind of person.”

Twice in church the previous Sunday Enid had turned her head and caught Chuck Meisner staring. She was a little fuller in the bust than usual, probably that was all. But Chuck had blushed both times.

“What is the reason you’re so cold to me?” she said.

“There are reasons,” Alfred said, “but I will not tell you.”

“Why are you so unhappy? Why won’t you tell me?”

“I will go to the grave before I tell you. To the grave.”

“Oh, oh, oh!”

This was a bad husband she had landed, a bad, bad, bad husband who would never give her what she needed. Anything that might have satisfied her he found a reason to withhold.

And so she lay, a Tantala, beside the inert illusion of a feast. The merest finger anywhere would have. To say nothing of his split-plum lips. But he was useless. A wad of money stashed in a mattress and moldering and devaluing was what he was. A depression in the heartland had shriveled him the way it had shriveled her mother, who didn’t understand that interest-bearing bank accounts were federally insured now, or that blue-chip stocks held for the long term with reinvested dividends might help provide for her old age. He was a bad investor.

But she was not. She’d even been known, when a room was very dark, to take a real risk or two, and she took one now. Rolled over and tickled his thigh with breasts that a certain neighbor had admired. Rested her cheek on her husband’s ribs. She could feel him waiting for her to go away, but first she had to stroke the plain of his muscled belly, hover-gliding, touching hair but no skin. To her mild surprise she felt his his his coming to life at the approach of her fingers. His groin tried to dodge her but the fingers were more nimble. She could feel him growing to manhood through the fly of his pajamas, and in an access of pent-up hunger she did a thing he’d never let her do before. She bent sideways and took

The man beneath her shook with resistance. She freed her mouth momentarily. “Al? Sweetie?”

“Enid. What are you—?”

Again her open mouth descended on the cylinder of flesh. She held still for a moment, long enough to feel the flesh harden pulse by pulse against her palate. Then she raised her head. “We could have a little extra money in the bank—you think? Take the boys to Disneyland. You think?”

Back under she went. Tongue and penis were approaching an understanding, and he tasted like the inside of her mouth now. Like a chore and all the word implied. Perhaps involuntarily he kneed her in the ribs and she shifted, still feeling desirable. She stuffed her mouth and the top of her throat. Surfaced for air and took another big gulp.

“Even just to invest two thousand,” she murmured. “With a four-dollar differential—ack!”

Alfred had come to his senses and forced the succubus away from him.

(Schopenhauer: The people who make money are men, not women; and from this it follows that women are neither justified in having unconditional possession of it, nor fit persons to be entrusted with its administration.)

The succubus reached for him again but he grabbed her wrist and with his other hand pulled her nightgown up.

Maybe the pleasures of a swing set, likewise of sky- and scuba diving, were tastes from a time when the uterus held you harmless from the claims of up and down. A time when you hadn’t acquired the mechanics, even, to experience vertigo. Still luxuriated safely in a warm inland sea.

Only this tumble was scary, this tumble came accompanied by a rush of bloodborne adrenaline, as the mother appeared to be in some distress—

“Al, not sure it’s a good idea, isn’t, I don’t think—”

“The book says there is nothing wrong—”

“Uneasy about this, though. Ooo. Really. Al?”

He was a man having lawful sexual intercourse with his lawful wife.

“Al, though, maybe not. So.”