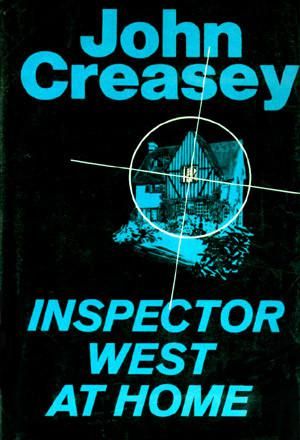

"Inspector West At Home" - читать интересную книгу автора (Creasey John)

|

JOHN CREASEY

Copyright Note

This e-book was created by

I am trying to create at least an ample collection of all the John Creasey books which are in the excess of 500 novels. Having read and possess just a meager 10 of his books does not qualify me to be a fan but the 10 I read were enough for me to rake up some effort to scan and create these e-books.

If you happen to have any John Creasey book and would like to add to the free online collection which I’m hoping to bring together, you can do the following:

Scan the book in greyscale

Save as djvu - use the free DJVU SOLO software to compress the images

Send it to my e-mail: [email protected]

I’ll do the rest and will add a note of credit in the finished document.

Frame-up!

Chief Inspector Roger ‘Handsome’ West opened his front door to Superintendent Abbott.

“I think you know why I’ve called,” said Abbott. He drew a folded slip of paper from his coat.

It was an official search warrant. . .

To save his career from being ruined and his name blackened. West plunges into a mystery that involves murder, international conspiracy — and corruption at the Yard!

Table of Contents

Copyright Note

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

CHAPTER 1

SUPERINTENDENT ABBOTT inserted his tall figure and expressionless face into the narrow opening of the door of the Chief Inspector’s office on B Floor at New Scotland Yard. Abbott seemed never to enter a door in natural fashion, but to slide in as if he were anxious to be unobserved.

When Roger West, who was in the office with Chief Inspector Eddie Day, looked up and saw the vacant face of the Superintendent, his heart dropped. He had schemed to take this particular day off, because it was his wife’s birthday, but he had been pessimistic until, when he had arrived an hour before, he had found a note from Abbott telling him to give details of one or two reports and go off. It was a dull, grey day, with early April making a passable imitation of late November; lights were burning over the desks furthest from the windows.

At the Yard, they called Abbott the Apostle of Gloom, for he was invariably the bearer of evil tidings, which perhaps accounted for his cold, vacuous expression.

Eddie Day looked up, pushed his chair back, and grinned. Eddie was not handsome, and when he grinned he showed most of his prominent front teeth.

“Oh, West,” said Abbott. “Will you be at home this afternoon ?”

Roger looked puzzled. “I expect so, yes.”

“Can you make sure that you will be in ?”

“I had thought of doing a show with my wife, but that wouldn’t be until this evening.” Abbott was not a man with whom it was wise to take liberties. “You’re not going to bring me back, are you ?”

“I just wanted to be sure where I could find you,” Abbott promptly effaced himself, closing the door without a sound.

“What a ruddy nerve!” Eddie declared. “Trying to put you in a fix so’s you don’t know what to do. I’ll tell you what, Handsome, take Janet out and let Abbott get someone else to chase round after him.” Eddie, who was a shrewd officer and at his particular job — the detection of forgery — head and shoulders above anyone else at the Yard, still looked and talked like a detective-sergeant newly promoted from a beat. “Cold as a fish, that’s what I always think the Apostle is.” Then he frowned at Roger’s expression. “Say, what’s biting you. Handsome? You look as if you’ve eaten something that don’t agree with you.”

“It’s nothing,” said Roger. “He might have given me one day without wanting me on tap.” He locked his desk and took his hat and mackintosh from a hat-stand. “Head him off for me if you can, Eddie.”

“Trust me,” said Eddie. “I won’t let you down. Give my love to Janet!”

His laughter echoed in Roger’s ears as he went out, and walked thoughtfully along the passage.

A soft drizzle of rain, a mist which threatened to become a fog and a sky of a uniform dull grey did not depress him. He slipped into a shop, for Janet, and contemplated an afternoon in front of a log fire after a good lunch at a hotel in Chelsea.

When he reached his small detached house in Bell Street, Chelsea, she was waiting in the lounge in a gaily-coloured mackintosh. She was tucking in a few stray curls of her dark hair beneath a wide-brimmed felt hat.

“Will I do, darling?”

Slowly, Roger West looked her up and down. As slowly, he began to smile. The wicked gleam in his eyes brought a flush to Janet’s cheeks.

“You ass !” she exclaimed.

“Yes, you’ll do,” declared Roger. “Although why we want to go out I don’t know. I’d much rather stay in. Catch!” He tossed the package to her.

She caught the package, moved to him and kissed him. “I thought we said “no presents, only a day out”,” she said. “Roger, you haven’t got to go back ?”

He laughed at her sudden alarm. “Not as far as I know. That’s not a peace-offering !”

Yet as she opened the present he wished that she had not reminded him of the Yard.

Janet enthused over a locknit twin set.

She dropped the set on a table. A few minutes later, with her hair slightly rumpled and faint smears of lipstick on his lips and cheeks, Roger had completely forgotten Abbott.

Throughout the meal, at the hotel ten minutes walk from the house, they talked of trifles. Only when they were in the lounge drinking coffee, and Roger could see into the street, did a frown darken his face.

“What’s the matter?” asked Janet.

“Nothing,” said Roger.

“Darling,” said Janet, “you can probably deceive all the criminals in the world but it’s no use lying to me. What did you see?”

“Now, would I lie to you?” asked Roger. “I caught a glimpse of Tiny Martin outside and wondered why he’s here. He’s been on a job at Bethnal Green.”

“Who’s Tiny Martin?”

“A sergeant who does Abbott’s leg work,” said Roger. “Let’s forget him.”

But Martin was not so easily forgotten. He was a tall, thin, cadaverous-looking man who always worked with Abbott and had something of the Superintendent’s strange coldness.

In spite of the drizzle, Roger and Janet sauntered along the Chelsea Embankment before returning to Bell Street. Twice Roger caught a glimpse of Martin, although Janet had completely forgotten the man and was busy speculating on Roger’s chances of a month’s holiday so that they could go abroad. They were still discussing it when they reached the house. He thought that he caught a glimpse of Martin at the end of the road, but dismissed the idea and went indoors. He sat back in an easy chair and told himself that he was both a happy man and a lucky one. He looked a little drawn — Janet knew that overwork explained it, but although there was a tinge of grey at his temples he looked absurdly young to be a Chief Inspector at the Yard. Their closest friend, Mark Lessing, frequently declared that Roger amazed him, so rarely did good looks and a keen mind go together.

“What time must we leave?” Janet asked.

“We shouldn’t start later than six,” said Roger, “the curtain rises at a quarter past seven and I don’t suppose we’ll be able to get a cab.” He reached out for his cup and then sat upright, hearing footsteps on the front path. The lounge was at the front of the house.

The footsteps were heavy and deliberate.

“Darling, why are you on edge so?” demanded Janet. “It’s probably the laundryman.” She put the lid over a dish of toasted crumpets and hurried to the front door. Roger glanced towards the hall, not knowing himself why he felt so worked up, until he heard Abbott’s familiar voice.

“Good afternoon,” said the Superintendent, “is Inspector West in, please ?”

“Yes, he’s at home,” said Janet, her tone reflecting the keenness of her disappointment.

“Ask him to be good enough to spare me a few minutes, will you? I am Superintendent Abbott of New Scotland Yard.”

“Yes, I know,” said Janet. She asked Abbott into the hall, then came to tell Roger, who was standing up and sipping his tea.

“Shall I ask him in here?”

“Yes, you’d better,” said Roger, reluctantly.

“I suppose I’ll have to offer him some tea,” said Janet. She made a moué and then went out into the hall again, but she sounded brighter as she invited Abbott to come into the lounge.

“It is a private matter, Mrs West. I would rather see him alone,” Abbott said.

Roger went into the hall with a manner which could hardly be called inviting.

“Wouldn’t a phone call have done as well?” He was on surer ground in his home than at the Yard. He saw Detective Sergeant Martin standing by the gate, looking gloomier because it was raining harder. Drops fell from the turned-down brim of his trilby. Roger frowned and added more sharply : “What is it?”

Deliberately, Abbott wiped his feet on the door-mat and shook the rain from his hat into the porch before putting it on the hall-stand. Janet closed the door. Abbott did not take off his mackintosh as he said :

“I’d like a word with you, West, alone.”

Feeling angry, Roger led the way to the dining-room. He stood aside for Abbott to pass and the Superintendent sidled in.

Roger waited as Abbott regarded him with narrowed eyes; he was a spare man with a curiously fleshless face and lips which were almost colourless.

“Well, what is it?” Roger’s exasperation got the better of his discretion.

“I think you know why I’ve called,” said Abbott.

“I certainly don’t,” Roger said. “And I hope it won’t take long. Is it the Micklejohn case?”

“It is not,” Abbott said. “West, I don’t wish to make this more unpleasant than I have to. You know why I’ve come and your aggressive attitude won’t help you.”

Roger stared. “Aggressive attitude?” he echoed. “If you mean a reasonable annoyance at being visited at home when I’m off duty —”

“I mean nothing of the kind,” said Abbott, and sighed, as if what he had to say was extremely distasteful. “I’ve come, of course, to search your house.”

Roger looked at him stupidly. “You’ve come to —” he began, then stopped abruptly. He was no longer angry, but was simply puzzled. “I wish you’d tell me what all this is about. It’s got past the joking stage.”

Abbott pushed his hand into his coat and drew out a folded slip of paper. There was something familiar about it; it was an official search warrant. Even when it was upside down he recognised the flourishes of the signature of Sir Guy Chatworth, the then Assistant Commissioner at the Yard, but until he had read it he did not really believe that it authorised Abbott to search

“I think you owe me an explanation. I have no idea what this is all about.”

Abbott did not immediately answer and before Roger could speak again, still shocked by Abbott’s announcement, a second knock came at the front door and Janet’s footsteps followed. He paid little attention to what was happening outside, but looked into Abbott’s narrowed eyes and tried to quieten the heavy thumping of his heart.

CHAPTER 2

“IT is not a pleasant task for me to present this warrant and X I think you should stop pretending that you know nothing about it,” said Abbott.

“I tell you I haven’t the faintest idea,” insisted Roger.

“Hallo, Jan !” cried a man from the hall. Roger recognised the voice of a close friend, Mark Lessing. Abbott was so surprised that he looked towards the door and Mark continued: “How’s the birthday party going?” There was a smacking sound and then, in a gasping voice, Janet said :

“Mark, you ass !”

“Now what is a kiss between friends on a birthday?” demanded Lessing. “Especially on the twenty-first — it

Abbott pinched his nostrils. “Well, West?” he said.

Roger was thanking the fates for sending Mark Lessing just then. Mark had given him time to realise that he would be wise to adopt a less hostile attitude. There was some absurd mistake, but it could be rectified.

So he forced a smile.

“I haven’t anything to say about it, Superintendent, except that I’m completely at a loss.” His attempt to be affable faded out in the face of Abbott’s cold stare. “Obviously you must have some reason for getting a warrant sworn for me.”

“You

Roger fancied that the faint emphasis on the ‘must’ implied a query. Before he could speak again, however, there came from the lounge an astonishing sound — astonishing because of the previous quiet. It was the deep, throbbing bass notes of the piano. Almost at once Mark began to sing, more loudly than harmoniously. A suspicion entered Roger’s mind : that Mark was drunk.

“Is that din necessary?” Abbott demanded irritably.

“Is any of this necessary?” asked Roger, tartly. “I thought I was going to have a day off. I’m taking my wife to a show as I told you. Are you serious about executing this warrant?”

“Of course I’m serious.”

“Why did you get it?” demanded Roger.

He had to raise his voice to make himself heard for Mark was going wild. He crashed wrong note after wrong note and he was thumping so heavily that the piano frame was quivering and groaning.

“If you will stop that noise I will tell you,” said Abbott. He stepped to the door. Roger had to go with him. When it was open, the whole house seemed to be in uproar, and he heard a bump upstairs.

Then he pushed open the lounge door.

Janet was by the mantelpiece, doubled up with laughter, for Mark was playing with idiotic abandon. As he crashed his hands on the keys he bobbed his head and his dark hair fell over his forehead; after each note he raised his hand high into the air, flexing his wrist. His pale face was flushed and his eyes were glistening.

“What the devil do you think you’re doing?” Roger demanded, striding across the room and grabbing Mark’s shoulder. “Stop it, you fool !” Mark continued, bobbing his head up and down vigorously.

“West, I insist that you stop this nonsense !” called Abbott.

“Nonsense?” he roared at Abbott. “Who the hell are you, sir? What do you mean by calling my playing

Abbott stared, tight-lipped. Roger, at first irritated by Janet’s laughter, saw an expression in her eyes which gave him his first inkling that she knew why Mark was playing the fool. She began to laugh again as if she couldn’t stop, and Abbott looked about desperately; Roger thought he bel-lowed ‘madhouse’. He did shout loudly enough to be heard above the playing : “Stop him. West!”

Roger tried, half-heartedly, beginning to wonder whether Mark could possibly be making this din deliberately, as a distraction. Roger remembered the bump upstairs. His confusion grew worse but he made a good show of losing his temper. Mark stopped at last and rose, disdainfully from the piano. He brushed his hair back from his forehead and straightened his tie — and then he jumped, as if horrified.

At no time handsome, he was a distinguished-looking man with a high forehead, a Roman nose and a pointed chin; his lips were shapely and his complexion so good that it was almost feminine. About him there was an air, normally, of arrogance.

Just then his whole expression was of horror.

“My sainted Cousin Lot!” he exclaimed. “Superintendent Abbott! Why didn’t someone tell me? I

“Of course,” said Janet. “Will you stay to tea, Superintendent?”

Abbott had listened to Mark’s protestations while gradually resuming a stony aspect. He turned to Janet, obviously ill-at-ease. Roger offered him a cigarette.

“Don’t get worried, Abbott,” he said. “All this will work itself out. Why don’t you have a cup of tea and talk about it?”

“What’s this?” demanded Mark. “Sticky business on the criminal stakes? Famous member of the Big Five flummoxed, Handsome West called in to get his nose on the trail?”

“You’re not going to take Roger away!” Janet protested. Abbott had the grace to cough in confusion.

Roger put him out of his misery.

“Not in the usual way, Jan, anyhow. I don’t know what’s gone wrong, but he’s turned up with a search-warrant. I must be credited with having broken open a till.”

“A search-warrant ?” gasped Mark.

Roger thought that they put a shade more emphasis than was needed, although he might have gained that impression because there was obviously something afoot between them.

Abbott appeared to think their amazement understandable and sincere; he coughed again.

“You can’t be serious !” exclaimed Janet.

“I am afraid I am, Mrs West,” said Abbott. “I really must not waste any more time.” He shot a quick, almost furtive glance at Roger. “Information has been lodged to the effect that you received, today, a sum of money intended as a bribe in consideration of withholding action when you knew that action was required.”

Roger stared, blankly.

“Let’s be serious,” said Mark. “A joke is a joke and I like one with any man, but this —”

“It is no joking matter,” Abbott assured him. “But for the peculiar circumstances, I would not have made the statement in this room. However, you appear to wish your wife to know, West. That is your responsibility.”

Janet stepped to Roger’s side.

“

Roger forced a smile. “Yes, he has a warrant, but it’s coining to something when he adopts this method instead of a straightforward approach. I suppose he could have come while I was out instead of while I’m here, but apparently that’s the extent of the consideration I can expect.” He seemed almost amused. “It’s all quite fantastic. It explains why Martin was dogging me, anyhow. He’s probably been making sure I didn’t pass the bribe on to anyone else!”

Abbott regarded him coldly.

“I can see nothing amusing in the situation, West.”

“I suppose not,” said Roger, dryly. “Hadn’t you better start searching? You’ll want to begin on us, but that doesn’t include my wife.”

“If it is necessary to search Mrs West — and I hope it will not be — I hardly need tell you the proper measures will be taken. Will you be good enough to call in Martin and the others ?”

“Others?”

“ There are two detective-officers with him.”

Roger nodded curtly, went to the front door and called the sergeant and his men. One of the plainclothes men was obviously embarrassed, but that didn’t stop him from doing his job properly.

The police finished downstairs and went up. Roger heard the heavy movements of the men upstairs and thought how often he had been on exactly the same quest.

He had searched with a thoroughness which had brought the tension of the people waiting in another part of the house to breaking point. He had worked with a grim determination to find some evidence of complicity in crime and to break his victim’s resistance. After the search, if it proved successful, came the arrest, the charge, the magistrate’s court, the gradual collection and piecing together of evidence, the final day of the assize trial. That last stage was often absurdly short in view of the weary weeks of preparations which had preceded it. Jury, judge, sentence — and prison.

He could not really grasp that this was happening to him. Instead of being the Apostle of Gloom, Abbott became the Apostle of Doom. For with every minute which passed one thing became more obvious. The Superintendent would not have come here, and Chatworth would not have signed the warrant, unless they felt reasonably sure that they would find evidence that he had accepted bribes.

He lit a cigarette and stared at Janet helplessly. Her lips curved in an encouraging smile.

The men were still moving about upstairs and time was flying — it was a quarter past five. Every minute worsened the suspense.

Janet turned restlessly towards the window.

“How much longer will they be?”

“Not long,” Roger said.

Mark broke in, reassuringly.

“After all, no news is good news. If they’d found the alleged evidence they would have come down by now.”

Almost as he spoke, footsteps sounded on the stairs.

The three turned towards the door, and only the plainclothes man seemed indifferent. All of the search party appeared to be coming and Roger, feeling a curious mixture of relief and tension, stared at the door handle. Someone spoke in a low-pitched voice but the handle did not turn. The front door opened and footsteps scraped on the narrow gravel path.

Roger muttered a sharp imprecation, stepped towards the door and opened it. Abbott was standing at the foot of the stairs.

“Well?” The word almost choked Roger.

“I want you to believe that I’m really sorry about this,” Abbott said. His lips moved so little that he looked incapable of feeling. He glanced towards the open door, and Roger, following his gaze, saw a woman approaching with Sergeant Martin. He recognised the newcomer as a tall, round-faced, jovial policewoman, one of the few female detectives at the Yard. Her purpose was only too apparent. He turned back to Abbott and spoke in a low-pitched, angry voice.

“I won’t forget this afternoon’s work, Abbott.”

“I am sorry,” Abbott repeated, expressionlessly. “Will you explain to your wife ?”

Roger turned on his heel. He caught Janet’s eye as he returned to the room. She gave him the impression that she had heard Abbott and was half-prepared for what was coming.

“They want to search you,” Roger said. “They’ve a woman outside, so they’re not breaking any regulations.”

The woman officer stood on the threshold, smiling as if it were the best joke in the world. She was the only one of the police who seemed untroubled by the situation. Roger stared when she winked at him before going upstairs with Janet to the main bedroom. Abbott entered the lounge and stared at Roger.

“All right,” Roger said. “Get on with it,” and allowed himself to be searched, standing rigid, neither helping nor impeding Tiny Martin, whose every movement seemed to be reluctant. The contents of his pockets were set out in neat array on a corner of the tea-table, next to the muffins which were now cold and unappetising, with congealed butter smeared on them. The fire had nearly gone out. Mark, suddenly waking out of a reverie, began to stoke it, putting on a few knobs of coal and two logs and using a small pair of bellows.

Tiny Martin finished and Roger looked at Abbott.

“Well, are you satisfied?” He could have crashed his fist into Abbott’s face.

“There is nothing here,” Abbott admitted. He took some brown paper and oddments of string from his pocket. “What was in this ?”

Roger stared. “I don’t know.”

“It is addressed to you and it’s registered,” Abbott said. “What was in it?”

Roger stretched out a hand and took the paper. It was familiar but nothing clicked in his mind at first. It was of good quality, with a typewritten address on a plain label. The postmark was blurred but, after some seconds of close scrutiny, he saw that it was franked December, although he could not distinguish the date. His face cleared and he handed it back, knowing both what had been in it when it had reached him and why Abbott had found it upstairs.

“It contained a Christmas present from my father,” he said. “Two first editions of Scott.”

“

“It was tucked away in my drawer for some months,” continued Roger, icily. “I took it out today and wrapped a birthday present for my wife in it. So it has quite pleasant associations. I carried it all the way from here to the Yard. It was folded up in my raincoat pocket when you saw me this morning. I went to

“Now, West —” began Abbott.

“ ‘Now West’ be damned!” growled Roger. “This is an outrageous visit. I may be a policeman, but I have some rights in law.”

Mark began to whistle a dirge. Roger swung round on him.

“Is that necessary? The piano’s still there.”

“I was only trying to while away the time. Ah! Sounds of progress.” Footsteps, this time of the women, sounded cm the stairs. Janet was first and she hurried in.

“Nothing at all on my person !” she declared. “I must say the officer made a job of it. Mr Abbott, perhaps you are satisfied now that my husband is not a renegade policeman?” She stared at the paper and snapped : “What are you doing with that?”

“He thinks the filthy lucre was wrapped up in it,” said Roger. “I’ve been giving him the history of it. Next time I bring you a present I ought to wrap it in newspaper or it will be used as evidence against me.” He thrust his hands in his pockets. Now that the search was over, except for this room, he felt much better. He insisted on staying while the room was searched methodically. Nothing was left out of place, perhaps because the work was done under Abbott’s cold eyes. When the man had finished, Roger eyed Abbott steadily and, after a prolonged silence, asked :

“Well, what’s the next shot in your locker?” For the first time he wondered whether they would take him away.

CHAPTER 3

HAD THE police made any discovery there would have been a formal charge; although they had not, they could still ask him to go with them for questioning. Abbott seemed not to hear Roger’s question but turned and motioned to Tiny Martin and the policeman — the woman detective had already gone. The lesser policemen went out and Martin closed the door.

Abbott looked even more discomfited.

“I don’t propose to do anything else now, West, but —”

“Now wait a minute,” protested Roger. “Either you give me a clear bill or I call for legal aid. I hope you realise that I can create the mother and father of a row.”

“You would be ill-advised —” Abbott began.

“What you seem to have forgotten is that I’m a policeman too,” interrupted Roger. “If there were any suspicions of a man at the Yard and I had charge of the case, I’d have the ordinary decency to tell him what allegations had been made, and ask him for an explanation. I would not burst into his house, risk upsetting his wife, accuse him —”

“I accused you of nothing.”

“You charged me with nothing but you’ve accused me of a damned sight too much. I want a full explanation and an apology.”

Abbott rubbed his chin, slowly.

“I think you had better come with me,” he said.

“If you want me, get a warrant.”

“Do I understand that you refuse to come with me?” Abbott demanded.

“You understand that I refuse to come to the Yard for questioning until I have had a more formal explanation of the reason for all this, and I’ve had a chance to get legal aid. That’s the least you would do if I were an ordinary civilian.”

Abbott’s mouth closed like a trap.

He turned and, without nodding to Janet or Mark, sidled through the partly open door and then closed it. There were muffled footsteps in the hall before the front door closed. Footsteps followed on the gravel path. Roger stepped to the window and saw the party disappearing towards King’s Road.

Roger turned to face the room, his lips curved in a smile which held no amusement.

“Sweet, I’m terribly sorry,” he said.

“Don’t be an ass,

“I’m not and before I’m through I’ll let Chatworth know what I think. I might have expected it of Abbott, but not of Chatworth.” He lit a cigarette and stared at the teapot.

“I’ll make some tea,” Mark volunteered, now very subdued.

He took up the teatray and went out. He had lived at the Bell Street house for some months and was familiar with every room and, as he often said, he liked to amuse himself in the kitchen.

Janet came over and sat on the arm of Roger’s chair.

“Feeling pretty grim?”

Roger said : “Damnable! I — but Jan, what’s Mark been up to?” He gripped Janet’s arm. “I’m so woolly-headed I forgot all about that rumpus. He sent you a tea set as a present, didn’t he? I’m not dreaming, you did have the parcel this morning?”

“Ye-es,” admitted Janet. “I was afraid you were going to say something about that before.” She stood up, stepped to the mantelpiece and took down a small cup and saucer, a fragile, beautiful thing. Idly, she flicked it with her finger; the china rang sweet and clear. “This was just to hoodwink Abbott.”

Roger said : “Did he know that Abbott would be here?”

“Yes.”

“And that din —” Roger jumped to his feet and stared at her, his eyes blazing. “There

“I only know that he told me he was going to make the devil of a row and the more noise I made the better it would be. Abbott did scare me and except for Mark the only light relief was when that woman took me upstairs,” Janet said. “She was a pet! She told me that she didn’t know what Abbott was up to and if he thought you were involved in shady work he must be off his head. You know her, of course ?”

Roger nodded. “She’s Winnie Marchant.” The loyalty of the policewoman cheered him up. “Come on,” he said, “I’m going to wring the truth out of Mark.”

Mark was leaning against the gas-stove, whistling gently, imitating the noise of the kettle, which was singing.

“Here it comes !” he said.

“Never mind making tea,” Roger said. “Janet will do that. What brought you here ?”

“Oh, my natural prescience,” said Mark, airily. “I heard a little bird tell a story about Abbott and Tiny Martin being on Handsome’s heels and I thought I would come and introduce a little light relief. Was I good?” He seemed hopeful. “If there’s any damage to that A string, I’ll have it put right at my expense.”

Janet took the teapot from him.

“Talk, Mark,” Roger ordered.

“I can’t tell you any more, except that the little bird was Pep Morgan.”

“Pep !” exclaimed Janet, swinging on her heels.

“Morgan?” echoed Roger. “Where does he come in?”

“The senior partner of Morgan and Morgan, Private Inquiry Agents telephoned me about half an hour before I arrived and told me to hurry over here,” Mark said. “He added I was to kick up the dickens of a shindy if I found Abbott on the premises. Had it been anyone else but Pep I would have told him to take his practical jokes elsewhere, but Pep wouldn’t play the fool. When I asked him why he told me to listen carefully if I wanted to save Handsome from Dartmoor. What else could I do but obey, Roger?”

Roger said slowly : “He must have had an idea of what Abbott was coming for and knew that if anything were found it would mean a long stretch.” He smoothed the back of his head and watched the steam hissing from the kettle, while Janet stood unheeding. Only when the lid began to jump about did she look away from Roger and make the tea.

“Let’s go into the lounge,” suggested Mark.

They went in, and when they were sitting around, Roger said :

“Pep was upstairs, presumably.”

“It seems likely,” admitted Mark.

“He wanted you to create a din while he got in upstairs and he —” Roger paused, boggling at the actual words.

“Took something away!” exploded Janet.

“We’re talking on supposition,” Mark said. “But if Pep learned that something incriminating was to be planted on you, obviously someone was to do it. There’s your problem — who and why ?”

“Yes.” Roger finished his tea in silence, then leaned back and studied the ceiling. The others did not interrupt his train of thought but Mark pretended to find some interest in a magazine. Suddenly Roger jumped to his feet, and stepped to the telephone in the corner of the room. After a short wait he said :

“Is Sir Guy Chatworth in, please?”

Janet stayed by the door, tensely. He was asked his name and then to hold on; he waited for a long time before Chat- worth’s servant — he had called the A.C. at his private flat, in Victoria — said that he was sorry but Sir Guy was not in and would not be in all the evening.

“So he won’t talk to his favourite officer?” Mark said.

“It’s fantastic!” exclaimed Janet. “I thought Chatworth was a friend. Roger, they can’t believe that you’ve done anything to deserve this. I mean — if they do they’re not worth a damn.”

“Indignant female expresses herself forcefully,” murmured Mark. “This is a conspiracy of silence. They wouldn’t have acted this way and certainly wouldn’t have put Abbott on the job if they hadn’t meant to make it as hot as they could, so they must have a good reason. It’s no use blinking at facts, is it ?”

“No,” conceded Roger, glumly, and that ended the conversation for some minutes.

“I suppose I should start getting supper,” said Janet, jumping up. “I won’t be long.”

She came back half an hour later with ham, cheese, bread, butter and a bowl of fruit. They finished supper and began the waiting game again.

They heard the gate open suddenly. Roger reached the front door before anyone knocked.

“Pep!” he exclaimed.

As soon as the door was closed again Roger switched on the light and looked at the smiling face of Morgan. A shiny man from his thin grey hair to his polished shoes — bright enough to see his face in, Morgan boasted proudly. In a good light, he scintillated. His cheeks shone like a new apple, his bright eyes gleamed, his astonishingly white teeth behind a full mouth seemed to sparkle. He was a chunky man, well- dressed but running to fat about die waist.

“Come in, Pep.” Roger led him into the lounge, where he shook hands ceremoniously with Janet and smiled at Mark.

“You did your stuff very well, Mr Lessing ! I was upstairs, and believe me I thought you would have the police on you for disturbing the peace.” He looked back at Roger and his smile grew strained. “Handsome, you won’t take me wrong, I know, but I’m staking my reputation on you.”

Janet and Mark seemed to fade into the background. Roger smiled, grimly, and asked :

“How’s that, Pep?”

“It’s a remarkable business, it really is. You’ve guessed I came here when Abbott was on the spot, and removed a little trifle from upstairs?”

“We guessed,” said Roger heavily.

“The little trifle was one thousand pounds,” said Morgan, softly. “One thousand of the very best in five-pound notes, that is what I found upstairs underneath your wardrobe, Handsome. Look!” Pep took out his wallet and extracted two clean five-pound Bank of England notes. “I’ve brought two of them. I thought I’d better not bring them all in case Martin saw me come in and wanted to know what I was doing — he

Roger stared at him.

“You must feel pretty bad about it,” said Morgan, “and so do I, Handsome. When I heard what was coming to you I came to the conclusion that it was a fix, and I couldn’t let you down. Lucky thing you’ve got some friends at the Yard.”

Roger said slowly : “What do you mean?”

“It was like this,” said Morgan, moving to the table and sitting on the corner. “No names, no pack drill, but I was chatting with one of the women at the Yard and she started to talk about you. Some o’ the ladies get a proper crush on him, Mrs West!” Morgan shot a sly glance at Janet. “She didn’t exactly

After a long pause, Roger said :

“And you found a thousand pounds in notes?”

“Two hundred five-quid notes as sure as my name is Pep Morgan,” declared Morgan. “I don’t mind admitting I was pretty scared; if they’d found that dough on me they might have asked a lot of awkward questions. So I tied it up and registered it to

“No, you didn’t slip up,” said Roger, smiling into the little man’s eyes. “Pep, I don’t know how to begin to thank you.”

“Oh, forget it. You’ve done me many a good turn, and I knew if they found that dough here you would have a taste of what you dish out to others, but I don’t believe you would take bribes.” He took out his cigarette-case but Janet stepped forward with a box. “Oh, ta,” he said. “Bit of a shock for you, Mrs West, I expect.”

“It certainly wasn’t a pleasure.”

“I’ll say it wasn’t! Well, I’ve told you all I know, Handsome. I needn’t say I know you won’t let me down.” He laughed and drew on his cigarette. “What a business it is, isn’t it?”

“Did Winnie Marchant tip you off?”

Morgan wrinkled his forehead and repeated :

“No names, no pack drill. Was she here ?”

Roger smiled.

“Yes. She gave Janet a piece of her mind !”

Morgan slid from the table and stood up, frowning, barely reaching Roger’s chin.

“Handsome, what’s it about?” he asked. “Who’d do the dirty on you like this?”

“I simply don’t know,” said Roger.

“You must have some idea,” protested Morgan.

“One day I will have.” Roger said softly. “I hope it won’t be long. Will you take a commission from me, Pep?”

Morgan’s little eyes glistened.

“I never thought I’d come to the day when a Chief Inspector would ask me that. Sure, sure. It’s all in the way of business, there’s no need for anyone to know how I came into it. You could have phoned me and asked me to try to find out whether anyone’s trying to put you on the spot. It would be a natural thing to do. What’s happened? Been suspended ?”

“Not yet,” said Roger.

“Nothing to prevent you from looking around yourself, then,” observed Morgan. “And Mr Lessing would lend a hand, as well as me. These fivers might help. Inspector West works from home, so to speak!” He laughed, quite gaily. “What do you want me to do for a start?”

“Make general inquiries, and try to find out whether anyone has a grudge against me. I suppose someone who’s just come out of stir might be behind it.”

“I thought of that,” said Morgan. “But it would have to be a big shot — I mean, a thousand quid isn’t chickenfeed. I’ve been thinking about those who’ve come out in the last month, and I don’t know of anyone who could lay his hands on a thousand. Still, I don’t mind trying, Handsome. There won’t be any secret about it, will there?”

“None at all.”

“Okay, then, I’m hired!” Morgan beamed, looked positively embarrassed when Janet came forward and kissed his cheeks. “He’d do the same for me,” he mumbled and hurried to the door.

Roger watched him disappear into the gloom, and followed. It was not quite dark, and he could make out Morgan’s shadowy figure. Suddenly he saw two others converge on the little man, and heard Detective Sergeant Martin:

“I want a word with you, Morgan.”

Morgan protested in a high-pitched squeak. Roger drew nearer.

CHAPTER 4

PERHAPS because he thought that Roger would be following, Morgan held his ground and complained at being frightened out of his wits. He talked to Tiny Martin and the other policeman luridly enough to cheer Roger as he drew nearer, keeping against the hedges of the small gardens of Bell Street so that he would not be noticeable if Martin looked round. Ten feet away, he stood still.

“There’s no need for you to behave like that,” growled Martin. “You’ve co-operated with us before, haven’t you?”

“I haven’t had anyone run out on me like that. What do you want?”

“Superintendent Abbott would like a word with you.”

“Well, he knows where I live. He seems to have gone off his rocker. So do you, Tiny.” Although still aggrieved he sounded mollified, a sensible reaction to ‘Superintendent Abbott would

“Never mind that,” said Martin.

He led the way towards King’s Road. Roger stayed on the other side until a bus lumbered out of the gloom, stopped for the two men and went lurching onwards. Roger turned back to Bell Street. The other Yard man was still near the house and Roger caught a glimpse of him across the road.

Roger went into the house but did not return to the lounge. He took his raincoat out of a corner cupboard.

“What are you doing?” Janet asked.

“I’m going to the Yard,” Roger said.

“Do you think —” began Janet.

“Is it wise?” asked Mark, outlined against the light of the lounge.

“I’m not suspended yet,” said Roger. T might pick up a hint from someone. If Winnie Marchant was prepared to let Pep know, one of the others might give me a hint of what it’s all about;” He put his hands on Janet’s shoulders and kissed her. “I don’t expect I’ll be late,” he said. “Make Mark play backgammon with you.”

There were tears in Janet’s eyes.

Roger went out, and paused on the porch to light a cigarette.

The plainclothes man was near the gate.

Roger drew on his cigarette so that his features were illuminated, then shone his torch into the other’s face.

“I hope it keeps fine for you,” said Roger. He was ridiculously glad that it was raining and cold enough to make the vigil an ordeal.

He did not get his car out, but walked briskly once he had grown accustomed to the gloom. He kept his eyes open for a taxi but had reached Sloane Square before he saw one. He was not sure that the Yard man had kept up with him, but thought it likely.

As he waited on the kerb while the taxi turned in the road, footsteps, soft and stealthy, drew near him. He took it for granted that this was the plainclothes man and took no notice. The taxi pulled up and the driver expressed himself tersely on the weather.

“You going far ?”

“Scotland Yard,” said Roger. The shadowy figure behind him drew nearer and he wondered what the man was thinking. As he was climbing into the cab, the figure moved forward and a soft voice, certainly not belonging to the detective, broke the stillness.

“Excuse me, sir.”

Roger turned his head, when half-in and half-out of the cab.

“Yes?” He was in no mood for casual encounters.

“I hope you won’t think this an impertinence,” said the stranger, “but I am most anxious to get to Piccadilly and the buses appear to have stopped running. I wonder if you would mind if I shared your cab?”

“What abaht askin’ me?” demanded the driver.

“Oh, yes, indeed — if your fare wouldn’t mind.” The man looked towards the cabby. Roger noticed that he wore a trilby hat pulled low and had his coat collar turned up. As he saw the pale blur of his face he thought, impatiently, that it could not have happened at a worse time, but he said:

“Of course,” and hoped that he sounded cordial.

There was no sign of anyone else nearby.

“Thank you so much,” said the stranger, eagerly.

“Op in,” said the driver.

Roger shifted to the far corner and the newcomer sat back with a sigh. He murmured that taxi-drivers were getting far too independent, it was most embarrassing to ask favours of them; it was very good indeed of Roger to allow him to share the taxi.

That was an invitation to confide, but Roger made an evasive remark and sat back. The other continued to talk of the weather, the cold war situation, the possibility of the bank rate going up, the price of houses and income tax. Roger made an occasional comment.

The cab drew up outside the gates of Scodand Yard, and the cabby opened the glass partition.

“Needn’t take you right in, need I ?”

“No, this will do fine,” said Roger.

He got out, stumbling over the other man’s outstretched legs. He paid off the driver and watched the rear light fading into the night. He heard the footsteps of the policeman on duty and, a moment later, a bull’s eye lantern was switched on.

“Is that necessary?”

“Oh — sorry, sir,” said the policeman, putting the light out hastily. “Nasty night, sir, isn’t it?”

“Bloody,” growled Roger and strode towards the steps. It was some consolation to know that the man had no instructions to stop him. He went up the steps and into the hall, where a sergeant on duty saluted. He was an oldish fellow with a wisp of yellow hair and very thin features. It might have been the light and shade of the hall, but to Roger he seemed surprised as he said “Good evening.”

“ ‘Evening, Bates,” grunted Roger.

He passed no one downstairs nor on the stairs, but the walls themselves seemed cold and hostile. He had never been in the Yard before without feeling a certain friendliness in its atmosphere. He began to realise how much the place meant to him. The dimly-lighted passages, shadowy now, seemed to hold a menace which was no less disturbing because its cause was unwarranted.

He opened the door of his office quickly and stepped inside.

Eddie Day was sitting at his desk with a watchmaker’s glass screwed to one of his prominent eyes. He looked up — and the glass dropped out, bounced from his desk and rolled along the floor.

Roger repressed a comment, loosened his coat and approached Day, looking down at the startled man.

“So you’ve heard, have you ?”

“H-h-heard w-w-what?” stammered Eddie.

“Why pretend that you haven’t, Eddie? Is it all round the Yard?”

Eddie closed his mouth, then bent down to retrieve the glass. His face was scarlet when he straightened up. Then he burst out:

“I’ve heard a rumour, yes!” To his credit he stopped pretending and did not try to make light of it. “You could have knocked me down with a feather. I don’t know what to make of it, I really don’t. You’re the

“I haven’t been told so.”

“Oh, well, perhaps that’s a rumour,” Eddie said hopefully. “I hope it is, Handsome. I can’t believe —” he paused and then went on : “Did Abbott have a search-warrant?”

“He did. And he used it.”

“Blimey!” Eddie pushed his lips forward and eyed Roger owlishly. “I just couldn’t believe it when I heard. When Bennett told me I thought he was joking, but he said he’d seen the warrant. What’s the Old Man got to say?”

Roger said : “The Assistant Commissioner hasn’t thought it worth discussing with me.”

“Strewth !” exclaimed Eddie.

“Eddie, do something for me,” said Roger softly. “If you know what they think I’ve been doing, if you’ve any idea from where they got the tip, tell me. I was pretty sharp with Abbott, because I know nothing about it. What do you know?”

“Handsome, I’m with you. I think it’s all a lot of nonsense. I can’t understand the Old Man. All I know is that you’re supposed to have accepted bribes over a period of the last three months.”

“From whom ?” Roger demanded.

“The squeak came from Joe Leech.”

“Oh,” said Roger. He stepped restlessly to the fireplace, where the fire glowed red. He knew ‘Joe Leech’, a bookmaker in the East End who kept within the law and was allowed to go to the extreme limits because he was a regular source of information to the police. His information was usually reliable and the police were often obliged to act on it. Few at the Yard had any liking for Leech, whose bad reputation in the East End was well known. Two or three times a year he had to be given police protection after he had squealed and friends of his victims had threatened violence. One thing was certain. Leech would not have done this unless he believed the allegation to be true or unless he had been heavily bribed.

“Don’t say I told you,” pleaded Eddie.

He heard someone approaching and put his glass hastily to his eye. The footsteps passed. Eddie stared at Roger with his glass at his eye, his forehead and nose wrinkled.

“It’s a bad do, Handsome, no doubt about that.”

He broke off when the telephone on his desk rang. He answered it and Roger judged, from his manner, that it was Chatworth. Eddie was more impressed by the Assistant Commissioner than most Chief Inspectors, although Chat- worth had a reputation for being a martinet.

Eddie replaced the receiver and stood up, gathering some papers from his untidy desk.

“Got to go and see the Old Man,” he said, in a confidential undertone. “He wants my report on those dud notes. You know the ones I mean.”

“Yes,” said Roger, with a flicker of interest. “Are they slush?” He thought of the £1,000 now at the Strand Post office waiting for ‘Mr North’ but it was too early to ask Eddie’s opinion of the two specimens; Eddie was not a man to be trusted in these circumstances. There were two Yard men who might take the risk of helping him, but one, Sloan, was on holiday.

“Stake my reputation on it,” said Eddie, half-way to the door. “They’re good, though. Er — best of luck, Handsome. If I can do anything let me know.”

Alone in the office, Roger looked about him, putting his hand in his raincoat pockets. He felt an envelope in there but thought nothing of it. The green-distempered walls displayed a few photographs, including one, old and faded, of a

Suffragette procession down Whitehall in 1913, two cricket XI’s one of them including himself, two or three maps of London districts and several calendars. On one of the desks was a small vase of fading daffodils. The fireplace was littered with cigarette ends and the carpet, with several threadbare patches, had a few trodden into it. The desks were bright yellow but, in places, the polish had worn off and the bare wood showed. There were little partitions for different papers –

He turned away, taking his hand out of his pocket and drawing the envelope with it. He looked down at the crumpled paper, frowning. It was thick and newish-looking; had it been in his pocket for some time it would have been grubby. He remembered thinking that morning that it was a fortnight since he had last worn his raincoat. He had not noticed the envelope then.

It was sealed and there was no writing on it. He inserted a finger at one end and ripped it open. Inside was a single slip of paper on which were two or three lines of block letter writing, upside down. He turned it swiftly and read :

Dear West,

I’ve another proposition I think will interest you. It will pay even better than the last. Meet me at the usual place, tomorrow, Wednesday, at 7.30, will you?K.

At first startled, then tight-lipped, Roger re-read it. All that it meant and all it might have led to passed through his mind, together with a fact which he had to face and which almost stupefied him.

A film of sweat broke out on his forehead.

To Abbott it would be just the evidence he wanted — and he had brought it into the Yard himself! He might easily have left his coat on a peg and gone to try to see Chatworth, which was his chief reason for coming. He stared down, studying the ‘K’ more closely; it was a carefully-formed letter; the whole note had been written by someone who knew how to use a pen. It was in drawing-ink, jet black and vivid against the white paper.

He screwed it up, with the envelope, turned, and placed it carefully in the middle of the glowing embers of the fire. It began to scorch but took a long time to blaze up. He heard someone approaching and turned with his back to the fire. As he did so the paper caught alight, making a flame bright enough to cast his shadow on the nearest desk. If someone came in and saw it they might try to retrieve the evidence.

The man outside passed, footsteps ringing on the cement floor. Roger stirred the blazing paper with his toe. In a few seconds it was just black ash, glowing red in places and giving off a few sparks which were quickly drawn up the chimney. He went to an easy chair to recover from the shock and to face the obvious fact; the envelope had been put in his pocket either at his own house or in the taxi.

CHAPTER 5

NO ONE came to the office.

Roger sat in an armchair of faded green hide. Nothing seemed quite real and the appearance of the note in his pocket seemed fantastic. He could remember every word and every characteristic of the lettering, the quality of the white paper and its thickness. He half wished he still had it, but it must have been too dangerous to keep.

Abbott must have searched the raincoat, so the note had not been there at five o’clock. No one had been in Bell Street except his friends and the police. The thought that Morgan might have put it there could be dismissed at once. The more he considered it the more convinced he was that the soft- voiced man of the taxi had inserted it when Roger had got out of the cab.

Roger stood up, and went to the door.

Chatworth’s office was on the next floor. Roger walked to the stairs and met two Detective Inspectors coming down. They looked surprised to see him. Along Chatworth’s corridor a door opened and Superintendent Bliss, broad and fat and with a voice like a dove, almost knocked into him.

“West!” he exclaimed.

“Bliss?” said Roger.

“Eh — didn’t expect to see you,” said Bliss and hurried off. Two men in the office stared at Roger as if at something strange. Tight-lipped, Roger went on to Chatworth’s office. There was a light under the door and he could hear Eddie Day’s sing-song voice. At the best of times it was unwise to interrupt Chatworth; he would have to wait.

Two corridors away was a common-room, for higher officials. It had a billiard table, table tennis, darts and all the paraphernalia of a club. Nearing the door Roger could hear the murmur of voices, and bursts of laughter. He went in and walked across the room without drawing attention to himself. Someone looked up from the billiard table and he heard his name uttered

He felt the blood flooding his cheeks.

No one spoke to him and he made no attempt to start a conversation. Fair-haired, youthful Inspector Cornish, who had recently been promoted from one of the Divisions, was the nearest approach to a close friend Roger had at the Yard. He was the only one here who might risk helping him.

Cornish looked up from an evening paper, coloured and averted his eyes. Roger turned on his heel. He was by the door when he heard his name called and, looking over his shoulder, saw Cornish hurrying towards him, his fresh face alive with concern.

“Handsome, do you know what’s being said ?”

“And believed, apparently,” rejoined Roger.

“

“You ought to know better than to ask,” Roger said. “It’s a

He went out, hearing the hum of conversation which followed. The door opened again and Cornish hurried after him.

“Roger.

“I did not.”

“Is there anything I can do?” asked Cornish abruptly.

Roger warmed towards him.

“If you really want to stick your neck out you can try to find out the name and address of the taxi-driver who picked me up at Sloane Square about three-quarters of an hour ago and dropped me here. I shared the cab with a man going on to Piccadilly.” That was as much as he dared ask.

“How will it help ?” Cornish demanded.

“I’m not going to let you get involved with details,” Roger said. “If you can find out just the cabby’s name and address, it could help a lot. Don’t take this too hard,” he added, cheerfully, “it won’t last for ever !”

He went on his way, grateful to Cornish, and was smiling to himself when he turned the corner. Sir Guy Chatworth, a large, burly man wearing a long mackintosh which rustled about his legs, and a wide-brimmed hat — nearly but not quite a Stetson, was shutting his office door. His large, round features were set in a scowl, by no means unusual. His natural colour was brick red.

“Good evening, sir,” said Roger.

Chatworth raised his massive head and stared at him.

He put the key in his pocket, and demanded heavily:

“What do you imagine you are doing here?”

“I’ve come for two things,” Roger said. “First, an interview with you, sir, and second, to apply for a release from duty for four weeks.”

“Oh,” said Chatworth, ominously. “You want release from duty, do you? Well, you can’t have it. You are suspended from duty.”

“That’s news to me,” said Roger. “I’ve had no notification, sir.”

Chatworth thrust his chin forward, narrowed his eyes, often round and deceptively wondering and innocent. “It isn’t dated until tomorrow morning. You’re being clever, are you, West? If you think you can apply for release and escape the stigma of suspension, you’re wrong.”

“I’ve been wrong about so many things that nothing will surprise me.”

“What do you mean ?” snapped Chatworth.

“I had always been under the impression that any man of yours would receive scrupulously fair treatment,” Roger said. “It was a nasty shock to find I was wrong about that.”

“You had your opportunity to discuss this with me,” Chatworth said. He stood by the door, feet planted wide apart, his mackintosh draped about him like a night-shirt which was too large. He pushed back the big hat and revealed his high forehead and the front of his bald head. At the sides was a thick fringe of close curls, blond turning grey.

“I had no such thing,” said Roger.

“You appear to be forgetting yourself,” Chatworth said coldly. “You were requested by Superintendent Abbott to come here to see me, and you refused. You were also insolent to a superior officer.”

“In the same circumstances any man should be “insolent” to an officer who invaded the privacy of his home, adopted an arrogant and overbearing manner to his wife and tried to take advantage of seniority,” Roger said clearly. “Superintendent Abbott appears to have misled you, sir. He did not say that you wished to see me. He asked me to go with him for questioning. As I knew nothing of the circumstances and he would not give me any information, I refused.”

Chatworth frowned, then dug his hand into his pocket. He took out the key, unlocked the door and pushed it open, striding into the room ahead of Roger, who followed without an invitation.

“Close the door.” Chatworth walked to his flat-topped desk. Everything in the room was modern, most of the furniture was of tubular steel, filing cabinets and desk were of polished metal which looked like glass. There was concealed wall- lighting and a single desk-lamp, all of which were controlled by a main switch.

Chatworth unbuttoned his mackintosh but did not take it off. He placed his hat on the desk in front of him and looked up at Roger, who was standing a yard from the desk without expression. Chatworth pushed his lips forward in deliberation, then said :

“I am grievously disappointed in you, West.”

“And I in you, sir.”

“Are you out of your senses ?”

“It is a very grave matter for me, sir,” Roger said. “I don’t think it has been properly handled. If a sergeant dealt with a parallel case in the same way I should have his stripes.”

He had burned his boats, but Chatworth would think no worse of him and it might enable him to force a hearing. He had won a minor triumph by getting into the room at all. He stood at ease, with one hand in his mackintosh pocket, and thought of the letter from ‘K’.

Then Chatworth nearly floored him.

“Who broke into your house while Abbott was there?”

“I don’t understand you, sir,” Roger said.

“Yes you do. While Abbott was in your house Lessing arrived and drummed on the piano while a man broke in through a first floor window, and removed the evidence which Abbott went to find. Don’t lie to me, West. You think that was clever, but it was a mistake.”

“To my knowledge there was never any evidence in my house which would convict me of accepting bribes. I have never accepted a bribe in my life. I don’t know where you got your information, nor how long I have been suspect, but

I do know that I think the methods adopted to trap me are disgraceful. You appear to have prejudged me, you’ve denied me the right to enter a defence. My best course, I think, is to refer the matter to the Home Secretary.”

“Are you trying to

“I am giving you notice of my intention,” said Roger. “That’s more than anyone did for me.” He paused but Chatworth simply sat back and stared at him; the desk-lamp shone on his polished cranium.

Looking at a man who had often been friendly and with whom he had worked for several years, one whom he had almost regarded with hero-worship, Roger felt a quickening tension. Until then, he had thought it just possible that Chatworth had deliberately planned to smear him so that he could work surreptitiously. The last hope should have died when he had found ‘K’s’ note, which was proof of evil intent.

Now he saw the situation for what it was — absurd but highly dangerous. Chatworth was not an ogre, but a reasonable human beneath his gruff manner. Roger stepped forward and planted both hands on the desk.

“I know that you must have strong reasons for what you’ve done,” he said. “You might at least give me the chance to answer the allegations. My record at the Yard should entitle me to that. The case must be more serious even than the seriousness of accepting bribes, or you wouldn’t have been so arbitrary. And Abbott’s visit doesn’t make sense.” He saw Chatworth going even redder. “If I were guilty, I wouldn’t be fool enough to keep evidence in my house.”

“That’s enough, West,” said Chatworth in a more reasonable tone. “Sit down.” That was a ray of hope. So was the way Chatworth pushed a box of cigarettes towards him. He lit up, and Chatworth bit the end off a cheroot. “For the first time I’m beginning to think I might be wrong,” Chatworth went on. “Why do you want four weeks’ leave?”

“To investigate this affair for myself.”

Chatworth unlocked a drawer in his desk and drew out a manilla folder. Roger leaned back and drew on his cigarette. The office was quiet except for the rustling of papers, until Chatworth glanced up and said sharply : “How do you account for seven payments of two hundred and fifty pounds paid into your account at the Mid-Union Bank, Westminster, during the last three months? Cash payments, always in one-pound notes. Where did you get the money?”

Roger was stupefied. “It’s not true!” he protested.

“Now, come. I have seen the account, talked to the cashier and the manager. Your wife made the payments.”

“Nonsense!” said Roger.

“Are you telling me that you don’t know what money there is in your account?”

“I use the Mid-Union bank only for occasional transactions,” Roger said. “It’s a supplementary to my main account at Barclavs, Chelsea. I’ve sent no credit to Mid- Union for at least six months. Nor has my wife.”

Chatworth said :

“Look at that.”

He handed a bank paying-in book across the desk. It was a small one, with half the pages torn out, leaving only the counterfoils. Roger saw that the first entries were in his handwriting — the book was undoubtedly his. He glanced through it, seeing a payment of fifty pounds which he had made in the September of the previous year. From then on — beginning in the middle of January — there were the payments which Chatworth had mentioned. The official stamp of the Mid-Union Bank with initials scrawled across it was there and the name at the top of each counterfoil was his.

Roger turned the counterfoils. The first shock over, he was able to study the writing and he noticed the regular lettering, it was almost copperplate writing,

“Well ?” demanded Chatworth.

“And my wife is supposed to have paid these in?” said Roger. “No, sir, it didn’t happen that way. The money has been paid in, all right. They’ve taken a lot of trouble to frame me, haven’t they?” He smiled, looked almost carefree. “I suppose someone representing herself to be my wife made the calls?”

“The description of the woman in every case is identifiable with your wife,” Chatworth declared.

“The description of any attractive, average build dark- haired woman with a flair for dressing well would do for that.”

“You seem remarkably pleased with yourself,” said Chatworth, sarcastically.

“I’m greatly relieved, sir! This is obviously one of your main items of evidence. My wife didn’t visit the bank and the bank’s cashiers will say so when they see her. You’ll arrange for several cashiers to see her, won’t you?”

“Yes,” said Chatworth. He leaned back and closed one eye. His pendulous jowl pressed against his collar, only half of which was visible. “You’re

Roger laughed. “Aren’t you letting yourself be carried away, sir?”

“If I were to advance a theory like that, without evidence, you would tell me not to go out on a limb,” Roger said. “Someone else paid that money into my account and whoever it was can be found. When she’s found we’ll have the answer to all this. May I ask what other evidence you have?”

Chatworth said in a strained voice : “West, are you a consummate liar or do you seriously suggest that you have been framed?”

“Obviously, I’ve been cleverly framed,” said Roger. “You can’t have any unanswerable evidence or you wouldn’t have waited so long before acting. You can’t charge me or you would have done by now. May I have that four weeks’ leave of absence, sir?”

“I don’t know,” said Chatworth. “When did you arrange for Morgan to break into your house?”

With anyone else, Roger might have given himself away. For years he had been used to such unexpected questions and he had trained himself never to be taken off his guard. His mood changed, however, but he felt sure that Morgan would have made no admission, so he answered promptly :

“I didn’t.”

“Morgan’s finger-prints were found in your bedroom this afternoon and he was seen visiting you this evening.”

“There’s no reason why his prints shouldn’t be there,” Roger said. “He’s visited me often enough.”

“Do you usually take visitors to your bedroom ?”

“Frequently,” Roger replied. “I use it as an office sometimes. Morgan has been helpful recently, and as soon as I realised what Abbott was after I asked him to help me.”

“Help you to do what ?”

“Find the answer to this mystery.”

Chatworth closed one eye again and looked at the ceiling. His fingers, covered with a mat of fair hair, drummed on the polished surface of the desk and Roger waited with growing tension.

CHAPTER 6

“What did he say?” demanded Janet breathlessly.

“Not a great deal,” said Roger, who had told them the story of his interview with Chatworth. “Apparently Pep’s story bore mine out. The denial that you’d been paying the cash in floored the old boy, I think. He was quite reasonable, as far as it goes. In the circumstances, suspension was the only thing, and leave of absence wouldn’t do. He’s right, of course. He gave me the impression that he expects me to get around a bit and will be prepared to listen to any evidence I dig up.”

“So I should think!” exclaimed Janet. “I’ll never like that man again.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” said Roger. “Those entries, occasional rumours from Joe Leech” — he uttered the bookmaker’s name very softly — “and other indications all pointing towards me, must have made it look black.”

It was nearly midnight but none of them looked tired and there was a kettle singing on the hob and an empty teapot warming by the fire. Roger was sitting back in an easy chair wriggling his toes inside his slippers. Mark was opposite him, and Janet was curled up on a settee between the two armchairs.

Tie didn’t tell you who’s supposed to have bribed you?” inquired Mark.

“No. He was reticent about that, which probably means that he doesn’t know for certain, but that he thinks the case hasn’t really broken open yet. He didn’t say much more,” he repeated. “A few generalities suggested that this is supposed to have been going on since about Christmas, when I hit upon some particularly clever racket and accepted bribes and held my tongue. Abbott’s been working on the case from the beginning.”

“What a snake he is,” said Janet.

“It wasn’t a pleasant job,” Roger replied, “and—”

“Darling, there are limits to the spirit of forgiveness.”

“Oh, I don’t know,” interjected Mark. “Better too much than too little, and although no one loves Abbott, he’s good at his particular brand of inquiry. When the cashiers have said “no” about Janet we’ll all feel better. You learned nothing else ?”

“Not from Chatworth. Eddie Day gave me Joe Leech’s name and Cornish promised to find the taxi-driver.” He had told them about the note from ‘K’. “If I can find out where the other passenger went it might help. The copper-plate writing and the paper — I wish I’d kept the envelope but I was too leery ! — the drawing-ink, Joe Leech and the woman who’s paid the cash in, and those five-pound notes. With luck and hard going we’ll get through. I wish I had some kind of idea why it’s being done,” went on Roger. “That’s one of the things at which Chatworth boggles most. Why should there be a deliberate attempt to frame me? I’ve been over the possible revenge motives, but Pep’s right. No one’s come out of stir lately who would be rich enough to try it. In any case, it’s too fantastic a notion.”

The kettle began to boil and he leaned forward and poured water in the pot. There were some sandwiches on a tray and Mark bit into one.

“The reason why,” he murmured. “That seems to be the first thing to discover, Roger. Shall I set my great mind to work ?”

“Not yet, thanks!” said Roger, horrified. They laughed. “Your first job, if you’ll do it, is to interview Joe Leech. Joe will be smart enough to outwit Pep.”

Mark grinned. “For that oblique compliment, many thanks ! Er — Roger.”

“Yes?”

“One little thing you might have forgotten,” Mark said, “and it could be significant. I mean, the attempt to involve Janet. The first assumption might be that it was just to strengthen the evidence against you, but it might also mean that the family is to be involved.”

Roger frowned. “I can’t think that’s likely. Did I say that Chatworth is going to send Cornish with you to the Mid- Union tomorrow, Jan? I think he’s afraid you will scratch Abbott’s eyes out!”

He laughed, and the atmosphere, already very much easier, grew almost gay.

The tension at the house while Roger had been out had been almost unbearable. It had been broken only by a telephone call from Pep Morgan, who had reported his encounter with Tiny Martin and told Mark that he had gone to the Yard and been questioned. He had been asked whether he had been at Bell Street earlier in the day, as well as to the reason why he had gone that night. Pep had answered on similar lines to Roger and had been released with a sombre warning from Abbott to ‘be careful’.

They went to bed just after one o’clock and, surprisingly, Roger went to sleep quickly. Janet lay awake a long while, listening to his heavy breathing and to Mark snoring in the spare room.

Mark was up first and disturbed the others by whistling in his bath. They breakfasted soon after eight o’clock and, just after nine, Mark left for the East End. Roger was tempted to go with Janet to the Mid-Union Bank, but thought it wiser to wait at Chelsea. She left soon after ten o’clock, met Cornish at Piccadilly and received the paying- in book from him and, at the small branch of the provincial bank made out a credit entry for fifty pounds, in cash, which Roger had taken out of his safe.

Cornish was nowhere in sight when she paid it in.

In spite of all the circumstances and her knowledge that she had never been inside the bank before, she felt on edge. The cashier was a middle-aged man with beetling brows; there was something sinister about him, about the tapping of a typewriter behind a partition and the cold austerity of the little bank itself. The cashier peered at her over the tops of steel-rimmed spectacles, counted the notes carefully, stamped the book and handed it back to her.

“Good morning, madam,” he said.

“Good morning,” gasped Janet and hurried out, feeling stifled.

She did not see Cornish immediately, but went by arrangement to the Regent Palace Hotel. She sat in the coffee lounge, and waited on tenterhooks. After twenty minutes Cornish came hurrying in, smiling cheerfully. Her spirits rose.

“Hallo, Mrs West!” Cornish reached her, his smile widening. “You’ll be glad to hear that he has never seen you before!”

Janet drew a deep breath.

“Thank heavens for that! I was half afraid that—” she broke off and forced a laugh. “But I mustn’t be absurd !”

“I’ve telephoned the Yard, so that’s all right,” Cornish said. “You’ll have some coffee, won’t you?”

“I must let Roger know first. I’ll phone from here.”

“Thank God for that,” Roger said over the telephone. “I was half-afraid that the cashier would go crazy.”

“So was I,” said Janet. “I suppose we’ll imagine idiotic things everywhere until it’s over. I must go, darling, Cornish is being very sweet. He’s getting some coffee.”

“Remind him to find that cabby’s address,” Roger said.

Smiling, he stepped from the telephone to the window and looked out into Bell Street. One of Abbott’s men was still on duty there. He felt like laughing at them, much happier now that he had a chance to fight back. Once the initial suspicion was gone, the whole organisation of the Yard would support him.

He hummed to himself as he lit a cigarette and then, frowning slightly, saw a powerful limousine drawing up outside the house. The driver glanced about him as if looking for the name of a house before pulling up opposite Roger’s.

Abbott’s man, betraying no interest, strolled along the opposite pavement.

A chauffeur climbed down from the car and opened the rear door. There was a pause before a woman stepped out. She was quite beautiful, and beautifully turned out in a black and white suit trimmed with mink.

Through the open window, Roger heard her say :

“I will go, Bott.”

Her voice was husky, the sun glistened on her teeth. She walked up the narrow path while the chauffeur stood at attention by the gate. As she disappeared from Roger’s sight, the front door-bell rang.

Before Roger went into the hall he smoothed his hair down and straightened his tie. When he opened the door he was smiling. It wasn’t difficult to smile at a woman as attractive as this stranger.

“Good morning,” he said.

“Is Mrs West in, please?”

“I’m afraid not,” said Roger. “I’m her husband.”

The woman said as if surprised : “You are Chief Inspector West?” !.

“Yes. Will you come in ?”

She hesitated and then said :

“I really wanted to see Mrs West.”

When he stepped aside, she entered the hall and he showed her into the front room. She moved very gracefully. Disarmed at first, Roger grew wary as she loosened the jacket, smiled, and sat down in Janet’s chair. “Will you please tell your wife I called?” she asked.

“Yes,” said Roger. “Whom shall I say?”

“Mrs Cartier,” replied the woman and took a card from her bag. “Mr West, I wonder if you will give me

“Us?” queried Roger, who had not looked at her card.

“To the Society,” said Mrs Cartier.

Roger glanced at the card, which was engraved : “

Janet worked for several welfare societies, and he assumed that Mrs Cartier had obtained her name from one of them. Yet he could not help feeling that her visit on this particular morning was a remarkable coincidence. He remembered that Janet had said that they would be reading sinister qualities in the most innocent matters; this was probably an example.

“How can my wife help you?” he inquired.

“Her enthusiasm and organising ability are so well known,” said Mrs Sylvester Cartier. “I have been told that she is quite exceptional. You know of our Charity, of course?”

“I’ve heard of it.”

“Then you will help to persuade her?”

Roger said : “I think I should know more of what you want her to do.”

“But that is so difficult to explain precisely,” Mrs Cartier said. “There is a great deal of work. Our Society will make strenuous efforts to assist the professional people among the refugees — who so often cannot be helped by the United Nations or other official organisations, Mr West. So many groups cater for the common man, but the professional classes need help just as badly. They must be rehabilitated” — she pronounced that word carefully, as if she had rehearsed frequently and yet was not really sure of it — “and enabled to contribute towards their adopted nations. I will not weary you with details, but please do ask your wife to consider my appeal for her services most sympathetically. I am at the office most afternoons between two and four o’clock.” She rose and smiled as she extended her gloved hand. “I won’t keep you longer, Mr West. Thank you so much.”

“Good-bye,” said Roger, formally.

Janet would have accused him of being in a daze as he saw her out and watched her get into the car; a Daimler. The chauffeur tucked the rug about her, closed the door and went round to his seat. The car purred off, revealing the Yard man on the other side of the road.

“Well, well,” said Roger. “I wonder what Janet will say?”

It was just after eleven and he did not expect Janet back until after twelve. He leaned back in his chair and tried to concentrate on his immediate problem.

The payments to his account at the Mid-Union Bank had started in mid-January. From that time someone had decided to try to destroy his reputation and, at best, to get him drummed out of the Yard. He had dismissed the possibility that it was revenge, but there must be some reason and he could imagine only that, about four months earlier, he had made some discovery which, if he followed it up, would have startling results.

“Some unwitting discovery,” he mused. “Something which made me more dangerous than a policeman would normally be.”

He began to go back over his activities in December. He had finished off three minor cases of burglary, one of forgery with Eddie Day’s help, one sordid murder case. He had made some inquiries into aliens living in England and whose activities were suspect. These aliens had succeeded in proving their good behaviour. Aliens—

He sat up abruptly.

Yet would the woman have come and risked setting up such a train of thought? If the mystery concerned the

Society, she would surely realise that it might start him thinking, and she might even know of his plight.

He went to the writing desk and began to make out a list of names, stopping only when his memory failed him. He grew so absorbed that even when Janet had not returned by one o’clock, he did not pause to wonder why she was so late. Nor did he wonder what progress Mark was making.

CHAPTER 7

MARK LESSING strode along the Street of Ninety-Nine Bridges, not far from London Bridge. He was a noticeable figure in that part of London. He seemed unaware of the dirt, the smells from small shops and markets, the grime which floated from the river and the spectral outlines of warehouses. Now and again he passed rows of hovels, some of them with the doors and windows open, most of them tightly closed and looking forlorn. Tugs hooted mournfully on the river. Covered gangways connecting one warehouse with another crossed the narrow street at intervals. Quays and locks, crossed by revolving bridges, were crossed with depressing frequency. Now and again he looked over the side of a bridge and saw the green slime undisturbed for many months. Yet there was a great hustle of activity, many voices were raised, horses and lorries passed along the cobbles in what seemed an endless stream.