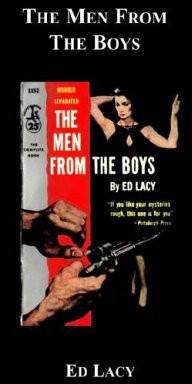

"The Men From the Boys" - читать интересную книгу автора (Lacy Ed)

|

The Men From the Boys

Ed Lacy

This page formatted 2005 Blackmask Online.

http://www.blackmask.com

OneTwoThreeFourFiveSix

For Carla Jump-Jump who faithfully manned the duty watches

One

As if I wasn't feeling bad enough it had to be one of those muggy New York City summer nights when your breath comes out melting. With my room on the ground floor and facing nothing, I lay in bed and sweated up the joint.

The summer hadn't been too rough till the last few days, about the time my belly went on the rocks, when it became a Turkish bath. I stared up at the flaky ceiling and wished the 52 Grover Street Corporation would install air conditioning. Almost wished I was the house dick at a better hotel. No, I didn't wish that—I had a sweet deal at the Grover. With my police pension, the pocket money the hotel insisted was a salary, and my various side rackets, I was pulling down over two hundred dollars a week in this flea bag— all of it tax free.

Turning over to reach a cool part of the sheet, this warm, queasy feeling bubbled through my gut. I belched and snapping on the table light took a mint. All I had on was shorts, but they were damp and as I started to change them, there was a knock on the door.

When I said, “Yeah?” Barbara opened the door, fanning her face with a folded morning paper. She never slopped around in a kimono or just a slip. Barbara was always neat in a dress and underthings, and shoes, not slippers. Which was one reason I let her work the hotel steadily. Her simple face might have been cute—ten years ago. Now it held that washed-out look that comes with the wear and tear. But her legs were still cute, long and slim.

She closed the door and leaned against it. “My—what a lump of man.”

“You should have seen me when I was younger and real hard—I looked like a tub then, too. What time is it?”

“Eleven-something. I'm knocking off, Marty. Ain't no customers. Guy'd have to be a sex maniac in all this heat.”

“All right, take off.”

She gave me a tired smile. “Dropped by to see if you wanted anything, maniac.”

“Beat it, you sweatbox.”

“You ain't kidding, I feel soggy. —Just me and Dora. Jean never showed. I left the money with Dewey.”

Another thing I liked about Barbara: she was honest. I got half of every three bucks the girls made. Out of that twenty-five cents went to Dewey, the night clerk, and he took care of Lawson, the bright joker who handled the desk during the day. Kenny, the bellhop, took another fifteen cents besides his tips. Out of my share I handled the pay-off to the cops. The 52 Grover Street Corporation got theirs in the usual way; there was a $2.50 room charge every time. It wasn't big time nor was it exactly penny ante. On a busy week end we often had ten girls working the hotel.

I got into a clean pair of shorts as she asked, “Hitting the sheets so early?”

“My stomach's been a brute. Gas, the runs, and feeling crummy in general.”

“Watch what you eat in this heat, Marty. Try some warm milk with a little rice; that will settle your belly. And lay off the bottle.”

“Honey, I can't even smoke, much less hold any booze down,” I said as the house phone rang.

“Wish my Harold couldn't hold it down. I'm in no mood for any rough stuff.”

“Tell your Harold if he puts a hand on you I'll knock his head from under his fat ears,” I said. That was a lie. I wouldn't mind working Harold over, I never had no use for pimps, but the 52 Grover Street Corporation wouldn't like the idea.

All I ever saw of the “Corporation” was Mr. King, an old and busy accountant who came around every day with his skinny nose up in the air. He was both auditor and hotel manager. Actually the Grover was owned by one of the largest and most respectable real-estate outfits in town. Which figured: “respectable” people always owned “houses.”

The phone rang again. As I picked it up, Barbara thumbed her nose at me, opened the door. “See you tomorrow, lover.”

“All right, honey.” Then I asked the phone, “What's the trouble, Dewey?”

“Couple of truckers in 703 hitting a bottle and making noise.”

“All right.” I hung up and started to dress. Never failed. When I wanted sleep some joker's whiskey had to start talking. Not that the Grover was very rough. Around 1900, I'm told, when this section was full of private houses, it had been a first-rate hotel with a view of the Hudson. Then it became an artists' hangout and speakeasy. When the midtown markets expanded, the Grover was just near enough to get a lot of truckers, along with a few seedy permanents —civil-service workers—and some transients who wandered in because they didn't know any better, maybe saw our roof sign from the highway.

Bending down to lace my shoes I brought up some gas and it was like an old sewer coming to life. I needed to see a doctor. The phone rang again. I grabbed it, told Dewey, “All right, I'm going up there!”

“Marty,” Dewey's soft voice said, “there's a cop in the lobby to see you.”

“Which one?” The greedy punks knew I paid off direct.

“New one. Sort of looks like a store cop to me. Youngster I never seen before. He asked for you.”

“Is he a cop or a uniformed guard?”

“Well,” Dewey hesitated, “he looks like a cop and then again he don't. You know, one of them Civil Defense cops, I think.”

“All right, tell him to wait. I'll see him in my office and straighten the bastard out.”

“Sure, Marty.”

I hung up and cursed. Things must be getting bad when a phony cop had nerve enough to be on the take. Hold his hand out to me and I'd break it off.

We had a small self-service elevator in the rear that the maids used during the day and I took it up to the seventh floor. These two clowns in 703 were singing and as I passed 715, Mr. Ross, one of the permanents, an old crotchety bald-headed bookkeeper, was waiting by his open door. He said, “Really, Mr. Bond, on a warm weekday night, this is an outrage!”

“They'll quiet down in a minute, Mr. Ross. Go back to sleep.”

“Sleep? In this heat?”

“The Grover isn't responsible for the weather,” I said, a poor joke that Ross didn't crack a smile over. Of course I could tell him a few things Barbara had told me about him that would make Ross hysterical, but I kept on walking down the hallway.

I knocked three times on 703, but the two of them were harmonizing on some hillbilly ditty and didn't hear me. They sure couldn't sing a little. I had my coat on and a tie, and my shirt was damp already. Opening the door with a passkey, I stepped inside and shut it quickly.

I'd never seen these truck jockeys before. They were both about twenty-seven, tall and lean, cocky punks. They were lying on their beds, each working on a pint, and wearing dungarees and shoes. There was an empty fifth on the floor. They jumped to their feet when they saw me. They were nicely built boys, ridges of muscles across their stomachs. The smaller one asked, “Don't you ever knock?”

“I knocked—you were blowing your nose too loud to hear me.”

The bigger one said, “Don't have to ask who you are— house dick written all over your fat puss.”

“That's me. Look, it's hot, I don't want no trouble. How about sleeping it off?”

“Want a shot?” the smaller trucker asked, waving his bottle at me.

“Too hot. I just want what you guys need—some sleep,” I said. This bitter-greasy taste suddenly flooded my mouth as the big one winked at his buddy. I got sore. On a steaming night these clowns wanted trouble, a little action. I got a mint in my mouth and chewed it quickly.

Big boy said, “We feel like singing. We're happy. Got us a load going back just like that.” He tried to snap his fingers.

“You want to sing, go down on the docks and sing your fool heads off.” I nodded at the beds. “Also, you ain't on the farm now and this ain't no pigpen—take your shoes off when you hit the sack.”

The smaller guy came toward me, waving his bottle. “Aw, have a drink with me.”

I wanted them both in close—although they didn't look like bottle throwers. I made one last effort. I said, “It's awful hot, no point in any of us working up a sweat. Take off your shoes and cut the singing! Tomorrow I'll take that drink.”

“Kind of old and fat for all that tough talk, ain't you, baldy?” the big one asked.

“All you whiskey-big-mouthed jokers give me a headache,” I said as I hooked the smaller one in the gut. He landed on the bed, skidded off onto the floor, fighting for breath and puking all over the old plush carpet. Big boy didn't move fast at all. I grabbed his bottle hand, jerked him to me and kicked his shin. He sat down hard, holding the leg, rye spilling over one bed.

“It's very hot, let's not have no more exercise,” I said.

“You fat bastard, I'll kill you!”

I pulled big boy up by his hair, planted a solid one under his ribs and let him sprawl on the floor. His hands clutched at his belly, clawing at the skin.

That was it: they'd never been hit like that before and their eyes were all fear. I said, “Either of you have any ideas about pulling a knife, forget it. I can give you a real beating if you're asking for it. I asked you in a nice way, but you hardheads got to get smacked down.” I glanced around the dirty room. If they had a return trip set, they were loaded. “You slobs made a mess of this room, ruined the rug. Be trouble if the chambermaid yells. Maybe hotel sues you. Best you leave her a tip—now.”

The smaller guy rolled over and dug into his pocket. “Be ten bucks to clean the rug, at least. And worth another ten for the work she'll have to do,” I added.

He waved a fistful of bills at me. Nothing like a wallop in the gut to take the starch out of a rough stud. I reached over—carefully—picked up two tens. As I opened the door I told them, “Now go to bed or poppa will have to spank again.”

“We'll never come here again!” big boy gasped. “You do, I'll throw you out the front door. Go to a flop joint where you belong.” I shut and locked the door, waited in the hallway for a moment. The clowns weren't marked —if they yelled they couldn't prove a thing. They were stupid drunk and fighting when I came in.

I was sweating a lot and stopped in at my bathroom, washed up, and it was a lucky move, for I got a sudden cramp. When I was ready I took a mint and called Dewey. “Room 703 is okay. Now send that jerky cop into my office.” In my office I took out my wallet and left it open on the desk so my card in the Policeman's Benevolent Association showed—to let the punk know who he was talking to.

He was a young cop, slight, with a skinny chicken neck, and the face looked a little familiar. He sure looked like a real cop, except for the patch on his shoulder, and the badge was smaller and the cap looked cheap. He had a gun belt on with bullets but no gun. Just a night stick and something in his back pocket that could be a sap.

He stood in the doorway, a silly grin on his narrow face, held out his arms like he was modeling the stingy uniform, asked, “Like it, Marty?”

For a moment I didn't recognize him. Hell, the last time I'd seen the kid was during the war, and he wasn't more than a dozen years old then. The grin on his face faded as he asked, “Marty, don't you remember me?”

The sort of plea in his voice did it. I jumped up and shook his small hand. “Lawrence, boy! Where do you come off with that not-remembering line? I was merely dazzled by the blue. Come on, put it down. When did you get the badge?” He always was a frail kid and now he looked compact, but like a weak welterweight. On his collar he had a gold A.P.—auxiliary police.

He sat down opposite me, pleased with himself. “Well, I'm not exactly a real cop. I'm with Civil Defense and we put in a few hours a week doing patrol duty—sort of practice for us, in case there ever should be an emergency, a bombing and all that. But I'm going to take the police physical next fall. I've been building myself up for it, go to the college gym every day.”

“How's your mother?” The kid had always been muscle-happy and cop-crazy. Maybe because he was always so delicate and sickly.

“Just fine. Guess you know she married again?”

“Yeah, I heard. Right after the war, and to some duck working in the aircraft factory with her. Hope she's happy. I gave Dot a rough time.”

“Mom never understood you,” Lawrence said. He had a good voice, deep and relaxed, and when you looked at his eyes for a while, you knew he was no longer a kid but a man. “Marty, I didn't mean to barge in on you so late, but I was just assigned to this precinct, and... uh... I thought you'd still be up.”

“I never hit the sack before three or four in the morning. Lately I've had some bum food and my stomach won't let me sleep anyway. You say you're going to college?”

He nodded. “Law school. I wanted to work and go nights, but Dot has been simply wonderful—insisted upon putting me through day school.”

“What's the idea of this tin-badge deal?”

He flushed. “Actually, I thought it would help me, give me a working idea of the force, so when I pass the physical and become a real...”

“You're studying to be a shyster—why you want to be a cop?”

He smiled as if I'd said something clever. “With the name Bond, what else could I be? Some of the men at the station, the regular police, asked me if I was related to you.”

“Down in this precinct—they remember me?”

“Every cop remembers you.”

“Are you... uh... defense cops under the precinct captain?”

“No, we have our own setup. Before this I was assigned to a station house up in the Bronx. But I mingle with the real cops.”

“They giving you a hard time because of me?”

He opened his collar, pushed his cap back, said flatly, “No one gives me a hard time, not the son of Marty Bond, the toughest cop on the force.” He sounded pretty hard. The kid could be more rugged than he looked—or nuts.

“That what they still call me?”

He turned his palms up, waved them. “Oh, a few said something about the... uh... Graham case, that you gave the force a black eye. But I told them off, reminded them you were the most cited man in the history of the New York City police force.”

“Graham—that lousy black bastard!”

“How's the hotel business?”

“Dull. Forget being a cop, Lawrence. It's a no-good job, everybody hates your heart.”

“I wouldn't say that. Laws are vital, living things to me that need protection, proper enforcement.” He lowered his voice. “After all, I not only have your name but my father died in harness. I belong on the force. And if I can only put on a little more muscle, I'll make a good cop.”

I was about to tell him there wasn't any such animal as a “good” cop, there couldn't be, but it was too warm to argue. So I said, “Hear there's a lot of college boys on the force.”

He grinned again and if it wasn't for his skinny neck he'd look okay. “Who isn't a college grad these days with the G.I. Bill? Did you know I put in two years in the army?”

“Get overseas?”

“No such luck, I never even got out of Fort Dix.” He looked around my office which seemed even crummier in the nighttime. “All this—hotel business—must be rather tame for you, isn't it, Marty?”

“Bounce a drunk now and then, catch a character running out with all his clothes on. That's about it.”

“Ever try your own agency?”

“That's strictly movie stuff.” There was a moment of silence till I kicked the drawer of my desk, asked, “Want a shot?”

“No, thanks. Are you still married to that dancer, Marty?”

“She wasn't much of a dancer. No, we busted up after a year or so. You married?”

“Not yet, but I will be soon as I get on the force.” His eyes studied my face. “Somehow you look... lonely... Dad.”

“Been a lot of years since you called me that.” The silly kid was always calling me Dad or Daddy.

“I always liked calling you Dad. Made me feel proud.”

“Yeah? So you think I'm lonely. I work and I sleep and the days go by. Except for this bad food I must have eaten last week, I get along okay. Suppose you've met Lieutenant Ash at the station house?”

“Indeed I did. Funny, I didn't recall ever seeing him, but he stopped me, asked if I wasn't Lawrence Bond, knew all about me. He looks like a square shooter, competent. How long were you partners?”

“Never added it up—maybe fifteen years. We were a good team. Used to say I was the brawn and he was the brains. Yeah, Bill Ash knows his business... I guess.”

There was another silence and the more I stared at the kid the more he looked like his father, except the senior Lawrence had been beefy. I never knew him—he'd walked into a stick-up and with a gun in his back had gone for his own revolver. I was pounding a beat then, and when the boys passed the hat for the widow, I was elected to bring the money to her. I often thought of Dot, the four years our marriage held up. She was a sweet girl, a real homebody. And Lawrence had been a quiet stringbean who thought I was the greatest thing ever.

I must have been daydreaming for quite a time, for suddenly he said, “Look, Marty, I've wanted to see you for a long time. But it was only when I talked to Lieutenant Ash that I even knew where you were. However I've also come to you for advice. A queer... uh... incident happened on my post a couple of hours ago and nobody at the precinct house is interested.”

I laughed. “I know how it is, your first collar always seems the greatest crime.... Wait a minute, can you volunteer cops make an arrest?”

“Yes, while we're on duty. Technically we're peace officers while in uniform. It's true this is the first... case... or trouble I've had, but I don't think that's a factor,” Lawrence said seriously.

I could hardly keep from smiling. Maybe he was twenty-one or twenty-two, but he still acted like a kid with a box-top badge. “What was the arrest?”

“There wasn't any arrest. You see, we do patrol duty in pairs and I was walking along Barren Street with my partner, an older man named John Breet. Well, the truth is he stopped at a bar to see if he could get a drink on the cuff. I don't go for that nonsense so I was standing outside the bar. A few doors down there's a small wholesale butcher, the Lande Meat Company. Not much, a double store with the windows painted black. The fact is, Wilhelm Lande, the owner, has had the place closed for the past several weeks. Willie, that's what they call Mr. Lande, says he had a stroke and his doctor advised him to take it easy. He's rather a nervous type.”

“What did he want you to do, steady his hand?” I corn-balled, thinking how batty a joker has to be to do police work for free.

“Marty, this isn't any joking matter. I have a feeling there's something seriously wrong here.”

“All right, you haven't even told me what the beef is.”

“Well, you see, they have to give us night tours, but they try to keep them during the light hours as much as possible. It was a little after 7 p.m. when a kid ran up and told me somebody had just broken the window of the butcher shop—from the inside. I didn't wait for Breet. I ran over to the shop and the door wasn't locked, and inside there's Lande the butcher tied up. He'd been robbed and trussed up around 6 p.m. according to his first statement, had finally managed to get ahold of a stapling machine, threw it at the window. I should say he was hysterical, almost in a state of shock as I untied him. He yelled he had been robbed of fifty thousand dollars by two teen-age kids.”

“Fifty grand? He must have a big insurance cover,” I said.

“That's one aspect of the case that has a false ring,” Lawrence said. “While I was taking down the details, and he gave me a fairly clear description of the kids, he suddenly shut up. Might call it abrupt, the way he did it. Said he had to make a phone call. Now, he has a little office in the store and a desk outside the office with a phone, and he dialed a number, whispered something about the holdup. I think I heard him say, Tm not sure, they knocked me out.' I wouldn't swear to that, but I thought he said that. The point is, he must have mentioned that a cop was there—you see, he thought I was a real policeman—for I saw him glance at me and nod as he said 'Yes, yes.' He listened for a couple of minutes, then hung up. When he came back to me, Lande was a new man, very calm, all one big smile. This will amaze you, he did a complete about-face in his story! He said the robbery had been something he dreamed, went to his icebox and brought out a canned ham, offered it to me, telling me there never was any fifty thousand, nor any two holdup men. Told me to forget the whole thing.”

I asked, “Where's the ham?”

“Marty, the man was trying to bribe me!”

“All right, all right, so you passed up a ham. How did he explain his being tied up?”

Lawrence pulled out a pack of butts, offered me one. I hadn't been able to smoke a cigarette all week, made me gag. I shook my head and as he lit one, sent a cloud of smoke out of his nose, the kid said, “That's the very first thing I asked about. He couldn't think very fast, gave me some clumsy cock-and-bull story about he'd seen an actor in a movie tie himself up, and he was trying it when he had an attack, felt he was choking, had thrown the stapling machine at the window to get help. He kept changing his story after the phone call. I wanted him to come to the station house with me, but he kept telling me to forget it, not to make a report. That's it. Like to see my on-the-spot notes?”

“No. What's the beef? He claims there wasn't any holdup.”

“But...”

“Lawrence, far as you're concerned it's over. Don't go looking for work, even when you're playing at being a cop.”

The kid flushed. “I don't consider this exactly playing— while I'm on duty I am a peace officer with certain powers.”

“All I meant was, don't stick your neck out unless you have to.”

“Wait till you hear the rest of it, Marty. I was in there about three-quarters of an hour. When I came out Breet wasn't in sight. I phoned the station house and the sergeant—our sergeant—bawled me out. Said Breet had returned and what the hell was I doing on patrol alone, all that. Our sergeant is a bit of a pompous old jerk, had me return to the precinct, wouldn't pay any attention to my story. So I went over his head, told Lieutenant Ash—he told me to forget it, too.”

“But of course you didn't?” I almost felt sorry for the kid, he was so badge-happy it was comical.

“No, I didn't. Truth is when we were dismissed I went back there—about an hour ago—and Lande was still in his shop. As I told you, he's nervous, talks a blue streak. Well, he made a slip. In his chatter he said, 'I got the money back.' I distinctly heard him say that although he denied it when I questioned him. He made a joke of it, asked where in the devil would he get fifty grand. As it happens, when I was returning to the station house I made a few casual inquiries in the neighborhood, at a bar and at a restaurant—Lande has been selling meat there for the last seven or eight years, does his own butchering, but has a small panel delivery truck and employs a driver. Everybody agrees he was lucky to clear five thousand dollars a year and...”

“Lawrence, you told him you were an auxiliary cop, didn't you?”

The kid nodded. “He noticed my shoulder patch when I returned, practically ordered me out of the store. I explained that...”

“You use your stick on him?”

Lawrence looked astonished. “Hit him? Certainly not.”

“Then he can't make any complaints, so what's troubling you? And even if you got bounced off this volunteer force, so what?”

“I don't have a 'so what' attitude. I plan to make the force my career and therefore ...”

“You talk like a bad cops-and-robbers movie, like a jerk.”

The kid went white and stood up. “Marty, you were a great cop, a top detective. I bring you a case, a crime, and all you can say is ...”

“Sit down, Lawrence,” I said, trying to make my voice soft. I slipped him a grin. “It's a hot night and we haven't seen each other for a lot of years. All right, maybe this is important to you, but as for me—one thing I learned while I was a kid—never work for free.” He sort of slumped in his chair and I added, “Seems to me you're making a fuss over nothing—the butcher isn't making any charges. And he could even jam you up—when you went back there you weren't on duty, had no police powers—not even as a peace officer, whatever that is.”

“I know that,” Lawrence said. “But if you could only have seen how hysterical he was at first—I believe he was robbed of fifty thousand dollars and that for some reason the money was returned to him.”

“Aren't you getting a little... uh... hysterical, kid? You said yourself he doesn't do a business to have that kind of cash around, and if he was robbed, why would it be returned to him? And in a few hours' time, too? It doesn't make sense. Far as you're concerned, forget it.”

The kid stared at me for a second, his eyes thoughtful. “Marty, I'm certain there was a robbery.”

“So what? You're not involved.”

“Not involved? It happened on my beat, and if for no other reason I'm involved because as a citizen it's my duty to report any crime I ...”

“You really believe this slop you're handing me?”

“I certainly do!”

“You better forget trying to become a cop, then. Kid, I'm going to give you some advice I'm sure you won't pay no attention to, but just in case you do become a cop, or even this part-time stuff you're doing, I don't want to see you make a fool of yourself. There's hardly...”

“I fail to understand your attitude toward the law, Marty!”

“Relax, and listen to me. There's hardly a day goes by in which the average citizen doesn't break some law—maybe letting his dog off a leash or spitting on the sidewalk. Also, there's hundreds of laws, maybe thousands, that don't make sense and shouldn't be on the books. For example, a girl can be hustling ever since she's thirteen, selling it a dozen times a day, yet until she's eighteen every one of her customers is guilty of statutory rape. Isn't that something, raping a whore!”

“A prostitute has rights, the protection of the law. The very fact that she may be under age proves...”

“Damn it, Lawrence, stop talking like a schoolboy reciting his lessons,” I said. “You dream of being a cop, then remember this—a cop only enforces the laws he has to, otherwise he'd go nuts—looks the other way whenever he can. Maybe this...”

“That's not my idea of law enforcement. At all times the...”

“Shut up! Maybe your butcher was robbed, maybe he wasn't. He says he wasn't. Maybe he also exceeded the speed limit driving to his shop today. Lawrence, what I'm trying to say is, don't be an eager beaver. Here you're only a volunteer cop for a couple hours a week, and you're already in an uproar over something that's none of your business. And don't hand me that honest-citizen crap. Lande's story is so wacky it can be true. He's robbed of fifty grand he says he hasn't, then an hour later the punks return the dough all tied in pink ribbons—probably said they were bad boys. Forget it.”

“I can't, there's too many weird angles. If only for curiosity's sake, I'm going to keep looking into this.”

“The cemeteries are full of curious people.”

“Marty, you've slowed down.”

“Maybe. And maybe if you were a stranger I'd knock you through the wall, badge, club, and all. Maybe that's what Lande should have done. Lawrence, I can't tell you what to do, but don't make a horse's rear out of yourself, especially if you might get on the force someday.”

“Marty, I'm not a kid looking for a thrill. I think there's something wrong here. I have a feeling, a hunch—and Lande's cockeyed story.”

I shrugged, dug for another mint. I was all out of the damn things. “Told you—you wouldn't take my advice. Do what you want, only try not to make a fool of yourself.”

He got to his feet. “Anyway, it's good to see you. I'll drop in to see you again, if you don't mind.”

I stood up and squeezed his shoulder. He didn't have much meat on him. “Where do you get that if-you-don't-mind slop? Drop in any time. Maybe we'll have supper together when my gut is hitting on all cylinders. You see Dot much?”

“Of course. I'm living at home.”

“Tell her I asked for her. Ain't you kind of old for still living at home? What's the name of your girl and are you sleeping with her?”

“That's none of your business, but we have been intimate. Name is Helen Samuels.”

“Sounds like a Jew.”

“She is. Why are you so bigoted, Marty?”

“You really going to marry a Jew-girl?”

“Why not?”

I shrugged. “I'm hardly the one to give advice on marriage. Also I'm not bigoted. I've known some pretty good nigger cops and Jew-boys. And Bill Ash is a Roman. I don't know, as a cop you got to start off by hating a lot of people, most people. Makes it easier to hate 'em if you hate their skin, their religion.”

He sort of laughed at me, punched my arm. It was odd, all of him was a kid except his eyes and his voice. He said, “You're like a rock, Marty, unchangeable. Remember when you gave me boxing lessons? I was a fair bantamweight in the army.”

We walked toward the door. “If I'd known you were going to be such a busybody, I would have given you lessons in kneeing and kicking.”

I walked the kid out to the lobby and said good-by. It was a few minutes past midnight on the clock behind the desk when I grabbed a morning paper, told Dewey, “Maybe I can get some shut-eye now.”

Dewey was a retired postal clerk, a moonface with watery eyes, and the veins on his fat nose like a complicated map—from the barrels of wine he'd guzzled during his sixty-eight years.

He said, “Too hot for sleep. The boy badge have his hand out?”

“No—merely dropped in to see me.”

“Funny-looking cop. He's too young to have been on the force with you.”

“He was my son—for a few years,” I said, walking toward my room. Dewey never even blinked.

I washed my teeth and took a shower, felt pretty good. Then I stretched out on my bed and read the paper, starting backward from the sporting page.

There wasn't a damn thing in the paper: the Giants' shortstop turned his ankle, the Dodgers still had a “mathematical” chance of getting the pennant, and the comics weren't funny. There was a cheesecake picture of some lush babe asking for a divorce because her marriage was “kissless.” A mild-looking guy named Mudd was accused of taking a bank for forty-five thousand dollars with a toy gun, and Albert Bochio, the syndicate treasurer, was still barricaded in a Miami hotel daring the authorities to boot him out, talking out of both sides of his mouth about suing the city of Miami for calling him a “gangster.” And the front page had the usual war scare. One of the columnists hinted that the fight game was crooked, and also commented on the fact Bochio was never so headline-brave before. There was a standard item about a Hollywood busted marriage “which will spill dirt all over the papers when it comes to court.”

I tossed the paper on the floor and turned off the light. Somehow the promised dirt never came out and I wondered if the columnists ran these items when they were short of material. And a guy has to have more courage than people think to use a toy gun in a stick-up. But they were right about Bochio—one of those unknown big shots. He was rapped once for assault when he was twenty-three, then dropped out of the gang picture till a Senate television show spotlighted him as the pillar of a swank New Jersey community, son at Yale, daughter in some finishing school... and holder of the purse strings of the biggest crime mob in the country.

I turned over a couple of times, got comfortable. Wondered how soon Lawrence would find out about me and the hotel. As a part-time cop he wouldn't know the score. And what did I care if he did?

It turned a bit cool and I covered myself with the sheet and dropped off. I awoke just before six, sweating like a pig, the dream still with me. Crazy, I hadn't had that dream in years... this Mrs. DeCosta's face screwed up with hate, screaming at me, “You thug with a badge!” I could see her plainly, as if she was next to me—and that wouldn't have been bad either, she was a fine-looking chick. What the hell she want to marry that crippled spick artist for?

Probably dreamed of her because I'd been thinking of Dot. Women... Now, why did Dot have to leave me because of that? The beatings were none of her business. And what finally became of the DeCosta blonde, or was she still in the loony bin?

I stretched and sat up, the stink still in my mouth. I was all done with sleep so I turned on the radio and then I got to thinking about Mudd who'd taken the bank with a toy rod. How did they know his name? Turning on the light I picked up the paper, read the whole piece this time. Amateur crooks are dumb as hell.... Mudd had been a depositor in the very bank he held up. By this time the cops would have him for sure.

I got up and showered. Except for my breath I felt pretty good. Not eating or drinking much, being on the run this last week, along with the heat, had taken about ten pounds off me. My muscles were showing again.

Dressing in a tropical blue suit that proved “bargains” aren't for big men, I walked through the lobby. One of the maids was starting to clean up, still half asleep, and Dewey was pounding his ear in the big chair behind the desk—his favorite bed. As I went through the doorway, Lawson the day clerk (and elevator pilot and bellhop) was coming in.

He was sporting a silk polo shirt and a crew cut, a big book under his arm. He was always reading, and was probably a fag—went around with the Village artists. He glanced at the way my suit hung on me, asked, “A circus come with that tent?”

“Why? You want a job as a fire-eater? Probably the only thing you don't eat.”

“Your humor is like your suit—it doesn't fit you. Up early, aren't you, Mr. Bond?”

“Yeah, I'm checking on your time.”

His thin lips gave me what passed for a sneer. “They got a nerve, with the twelve-hour day I put in.”

“You going for a union here?” Wouldn't surprise me if the smart bastard was a radical. We all put in long hours, but the gravy was worth it. And Lawson didn't do a damn thing but read. We never got busy till late afternoon and Dewey was on then.

I walked over to Hamilton Square and had coffee and toast, got hungry and knocked off a stack of pancakes, a hunk of pie, and more coffee. It was only seven and I had nothing to do.

Walking over to Washington Park, I sat around for a while watching some old nut open a bag of crumbs and feed the pigeons. When a couple of them hopped up on his hands, he glanced at me proudly. I decided to take a bus ride uptown, buy some socks and a couple of shirts. I rode up to Fifty-seventh Street and then down to Macy's, but the store wasn't open yet. I had a glass of iced coffee and tried smoking a cigarette.

A lot of gas hit my stomach and I began belching, so I took an Alka-Seltzer and bought a pack of mints. The pain in my gut hit me and I forgot about shopping.

I phoned Art Dupre's office and got one of these answering services. I found his home phone in the Bronx book. He answered with “Dr. Dupre speaking.”

“Doctor, I'm in trouble,” I said in a gal's voice.

“Who is this?”

“Oh, doctor, I'm in trouble and I ain't married and the druggist said you'd fix it for me.”

“Who is this? What doctor do you want?”

“Oh, you a doctor? I want Sergeant Dupre!” I said in my regular voice.

Art said, “Marty Bond—you and your lousy gags. How are you?”

“Got a touch of ptomaine poisoning, or something, Art. My belly is acting up. Can you work on me sometime this morning?”

“Of course. How about eleven?”

“All right.”

“How sick are you, Marty? Vomiting?”

“Naw, but I feel like it at times. Mostly the runs and an upset gut. I'll live till eleven—the question is, Will I live after you work on me?”

“That's a bright question, the enlisted man's dream come true—having his C.O. coming to him for help. See you at eleven, and don't drink anything cold or strong in the meantime.”

“Okay, boy.”

I still had a couple of hours to kill so I took the bus downtown. The sun was already out strong, another scorcher. I took off my coat and thought about going to Coney Island, or surf casting at Jones Beach. But I was looking forward to seeing Art. He'd been a medic in my M.P. outfit and saved me from a lot of grief over in England when I nearly killed a cocky A.W.O.L. wop.

That kid Art had the stuff, he wanted to be a doc and he'd made it. G.I. Bill was something, except for us older guys. I would have looked silly going to college. And what could I learn — you never needed no bill to go to my college, the University of Hard Knocks.

I got off at Hamilton Square and headed for the precinct. Some white-haired bag was standing on the corner, rattling a red tin can. Pushing it up in my face, she gave me the pitch-smile as she asked, “Please help fight cancer?”

“Let the government shell out the dough for it. They're always spending dough like water.”

“We must all chip in and do our part,” she said sweetly. She probably worked for a percentage of the take.

“Your sexy smile does it, sister,” I said, dropping a couple of dimes in the can.

“Thank you. Like to put this on your coat?” She held up a red tin button shaped like a sword.

“They giving medals for being a sucker now?” I asked, winking at her and walking on.

It was a big morning for me. When I asked the desk man for Lieutenant Ash he said, “The lieutenant isn't in yet. What do you want to see him about?”

He was another of these slim cops, young too — under forty. “Just dropped in for some chatter. When do you expect him?”

“About noon.”

“I'll be back. Tell him Marty Bond called.”

“I'll tell him.” He gave me a mild stare.

“Yeah, Marty Bond the ex-cop,” I said, walking out. I dropped in at the Grover and Lawson said, “Mr. King is in the office.”

“So what?”

“Just thought you'd like to know. Room 703 checked out leaving the room a mess. The rug will have to be cleaned.”

“It's about time.”

“Mr. King was miffed about it.”

“He miffs too easy.” I took the elevator up to the seventh floor. Lilly, one of the old colored chambermaids, was cleaning 703. She said, “Look at this mess. It's disgusting.”

“Couple of drunks. I had to quiet them last night. By the way, Lilly, they left this as a tip for you.” I handed her five bucks. “Clean up the room good before King comes sniffing up here.”

She pocketed the fin quickly. “I'll take care of it. That was nice of them to think of me.”

“I sort of suggested it. Put it all on a number and you can retire—maybe. What do you like for today?”

“I usually stick along with my house number, 506.”

“All right, play a buck for me.”

“I'll get it in. Where's the money?”

“Lilly, out of the five. Wasn't for me you wouldn't have nothing.”

I went down to my room, considered shaving, dabbed some after-shave lotion under my armpits, put on a fresh shirt, and went out. Art had his offices on East Fifty-eighth Street—pretty swank. I took a bus to Fifty-second Street and walked through the ratty section between Sixth and Fifth Avenues that's full of night spots. I knew Flo was stripping in one of the joints and for no reason I wanted to see her picture.

She wasn't the feature strip; they only had an 8” x 10” of Flo, one of her old snaps. I stared at the strong long legs, the hard body, the hard beautiful face, the small, perfect breasts. This snap was taken nine years ago, but Flo hadn't changed much. Whenever she worked one of the burleycue houses in New Jersey, I'd go over to watch her. Almost gave me a queer bang to see the clowns gaping at her, recalling all the times I'd had what they were eyeballing.

Although I never really had Flo. I was tough, but she was tougher. She was about the toughest babe I ever knew. She knew what she had, and her only aim in life was to make it pay off in folding dough. I remembered the first time I saw her, in the chorus of a crummy Broadway musical. Guess she went with me for a resting period. My salary gave her a chance to hunt around for a feature role, study up on her dancing and acting. Everything she did was part of this drive to “get to the top.” You couldn't even beat this drive out of her—I tried it a couple of times.

Maybe one of the reasons I got a kick out of seeing Flo do her act, these last couple of years, was the satisfaction in knowing she'd never made the top. She left me for a bastard who took her out to Hollywood. Flo had all the whistle stops, enough ability, but she must have slept with the wrong jokers. Over the years I'd see her in a few bit parts, then in '48 she started doing burlesque work, night clubs. Flo had to be hitting thirty-eight or thirty-nine now, just sticking around for the crumbs.

I walked slowly toward Madison Avenue thinking of Flo. If only she had had something in her blood besides ambition we might have hit things off—for a short time we had it pretty good. I used to wake up in the middle of the night, light a match and stare at her, wondering how a slob like me ever got so lucky. Dot had the brains and the warmth, Flo had the body. Although Dot could surprise the hell out of you—sometimes.

Art was sharing the first floor of a brownstone with two other doctors. I gave the nurse at the reception desk my name and she told me to sit down. I slipped a mint in my mouth and watched her legs under the desk, wondered why I was looking—Barbara had better stems. And in any event what good would...?

I belched and watched her face to see if she'd heard. She hadn't. I glanced around the office, all the modern furniture. The last time I had Art work on me was a year ago. He had a modest office up on Eighty-third Street then. The boy was climbing fast.

After a couple of minutes Art came in, looking fine in his white jacket. Although he wasn't a ladies' man, he could be—had one of these lean, homely maps that women go for, like Gary Cooper. And Art was big and fairly muscular although he never did any physical work or exercise. Once in the army when we were swimming in Venice, I asked him how he stayed in shape and he'd said, “I don't know, lieutenant. I suppose I was just born this way.” Art never called me “sir,” always “lieutenant,” which was okay with me.

After the usual hard handshake and cracks about neither of us looking a day older, I followed him into his neat office, sat down in a chair that looked like a giant ice-cream cone and which turned out to be comfortable. “How's the hotel business, Marty?” he asked, taking out my file.

“All right. With the housing shortage, hotels are making out.”

He nodded, as though he was interested. “What's all this about ptomaine? Upset stomach? According to my records you're a typical hard rock. An interesting specimen, a throwback, as I kept telling you, a ...”

“All right, cut the big words. So I'm a specimen, pickled in alcohol, and all that. Art, I think I have a case of the old G.l.'s. Been that way, off and on—and that's no pun—for the last few weeks. Nothing seems to help. Also, I have a lousy taste in my mouth, like something died in me a long time ago.”

“Any fever or chills?”

“Nope, I don't think so. I sweat, but that's because of the dog days we've been having. I belch a lot.”

“Still drinking?”

“Nope. Funny thing, haven't had a desire for a shot, or for a cigarette either.”

“According to my records you haven't had anything worse than an acid stomach in the last five years. You look like your usual burly gorilla self. Though what's left of your hair is turning gray. Marty, you worrying about anything?”

“Me? I never worried in my life.”

He stood up. “I'd say you're in good shape—for an old man.”

“I'm only fifty-four, you punk.”

“Okay, pops, take off your shirt and I'll give you the works.”

The boy really gave me a thorough examination, worked me over with several gadgets, put me in front of a fluoroscope... all the time asking questions about what I liked to eat and what I didn't, the color and shape of my bowels, any pains, and other exciting remarks.

At first we were wisecracking a lot, but after a while I knew he was putting on an act with the gags—Art was really damn serious, even frightened.

After about an hour he told me to dress and we sat down at his desk. Art asked,. “Marty, you say you're always tired, weak, not much of an appetite, lost weight and...”

“All right, Art, stop stalling, what's wrong with me?”

“Well,” he said slowly, “I think you have a tumor, a growth next to your intestines... far as I can make out. You may need an operation. I'm sending you to a specialist for a gastric X ray. He'll know much more about it than I do.”

“I have a tumor in my gut?” I repeated.

“I thinly you have one.”

“Can't penicillin, one of these new wonder drugs, do the trick?”

“Perhaps. We'll see what the specialist says. You may not even require surgery. But I think it will be best to take a sample of the growth. Merely routine...”

“A sample? You mean it might be cancer?” The words seemed to sting as they tumbled out of my lips.

“Might be anything,” Art said casually. “Marty, I'm only a pill-and-temperature man, wait till we hear what the big shot says. I can be all wrong about it being a tumor. I'll make an appointment for you.”

I sat like a dummy, hearing Art pick up the phone, make an appointment for 1130 the following afternoon. I couldn't think. All I could do was taste the dry garlic stink on my tongue. There was a horse cop I knew who died of cancer of the gut. He'd been a pro boxer once and we used to work out together. He'd starved to death because the cancer squeezed his intestines tight. I spent a lot of time with him in the hospital, watching him become a bag of bones.

As Art put the phone down I told him, “I was never afraid of dying because if you don't fear death you got the world by the tail. But this... what a crummy way of going out.”

“Stop it. It could be an ulcer, an inflated stomach, a hundred and one things besides ...”

“Don't talk a hole in my head, Art!”

He stared at me for a second, then pulled a pipe out of a drawer, carefully packed and lit it. “Marty, this isn't something you can lick with hard talk or slugging, so don't be a goddam amateur doctor. Every growth isn't cancer, just as every headache isn't a nervous breakdown. If it is a tumor they cut it out and in a few weeks you're good as new. It's that simple.”

I shook my head. “It'll be cancer.”

“Oh for—How do you know? I...”

“Hell, I just know!”

“You're spouting sheer nonsense. Wait till you hear what the specialist tells you tomorrow before starting the dramatics and self-pity. Not like you, I always thought you were too tough for fear.” Art smiled. “That's hot air I'm handing you, Marty. I don't blame you for being frightened, but if I don't know what it is, you certainly don't. Let me know what the specialist tells you tomorrow.”

“As if he won't call you. Art, if it should be cancer, how much time ...?”

“I refuse to answer that, even think of it.”

“I once knew a guy that had it, right in the gut too. Lay in bed for over three months before he finally kicked off, looked like a goddam skeleton.”

“Marty, let me give it to you straight. If it is cancer you may die. I said if and may. Not every cancer patient dies, most of them live. As for dying, you know the old bromide— a car may splatter your brains all over the street the second you leave this office.”

“Hell, that's quick.”

Art came around the desk, slapped me on the shoulder. “Marty, you make me ashamed of myself for being such a bad doctor, scaring a patient. Wouldn't have told you except I thought you were such a tough bastard. I don't have the knowledge or equipment to diagnose this, so if it turns out to be a gas pocket, something as silly as that, don't try to whip my head. Now, here's the specialist's name and address. Be on time and be ready to shell out about fifty bucks. Need any money?”

I got up. “No. What do I owe you?”

“I enjoyed your company.”

I dropped a five spot on his desk. “This do it?”

“I told you...”

I shoved his hand away. “I've heard that north wind before. So long, Art.”

“Marty, let's have supper together. I never see you except when you're sick. How about making it for Friday...?”

“Sure. I'll call you.”

I walked out, passed by the receptionist, and the lousy taste was strong in my mouth. The taste of death, the greasy crummy taste of death. I stood on the sidewalk for a few minutes trying to swallow, clear my mouth. The sun was making me sweat. I didn't know what to do. I wanted to talk to somebody, go home. But home was a flea-bag hotel room.

I had a sudden desire to see Flo, to be with her in the flashy four-room apartment we used to have, the little bar and bar stools like in the movies. There was the bedroom with Flo's dolls....

Dolls made me snap out of it. I had no time for dolls or for much of anything else. I walked to a corner drugstore, bought some mints and drank two glasses of orangeade that I damn near threw up.

I took a cab down to Hamilton Square. Bill Ash had been my boon buddy for a lot of years. He was a good listener, a guy with a level brain. I crossed the Square and headed toward the station house. Bill and I had been attached to a precinct uptown for almost six years before we were sent... The white-haired lady with the red tin can came over to me. “Will you help fight...? Oh...” Her mechanical smile vanished and she turned away.

Grabbing her arm, I jerked her to me. “What's the matter? You see something on my face?”

“Why... mister... My God, you're hurting my arm!”

“Tell me what you see on my face?”

“See? Nothing. I don't see anything!” she said, hysteria loud in her voice. “I remembered that you contributed before, this morning. That's all.”

People were staring at us. I let go of her arm. “Excuse me. I was... uh... thinking of something else. Here.” I dumped a handful of change in the can.

“Thank you so much.” She recovered herself, clumsily tried to pin one of the red buttons on my lapel.

I shoved her hand away. “I already got my badge, the real one.”

Walking toward the precinct house I told myself I had to watch it, I damn near hurt the woman. And tomorrow, this smart-aleck specialist would probe and ask a lot of stupid questions. Hell, I never had no confidence in docs, except for Art.

As I walked up the steps of the police station, which looked like all New York City police buildings—older than God— I decided I wasn't going to see the specialist. What could he tell me? What point was there in being sliced open, letting them sample the lousy tumor? It always turns out you have it.

The desk man told me Bill was busy but phoned my name in. I stood by the desk and wiped my face, the humidity was as bad as yesterday. I put a couple of mints to work in my mouth and now I could almost see the taste, like I was chewing something misty and black.

There was an air of excitement around the precinct. Nothing noticeable, not a lot of activity, but you could sense it. Every time a couple of guys passed the desk they'd be talking with each other in low voices. And there would be a sort of rush in their steps. I waited long enough to finish a mint, blotted the sweat on my face again, asked, “Is Ash alone?”

“I think so, but Lieutenant Ash is very busy and doesn't...”

I walked back toward the detention cells, past the “Post Condition" board, then up a flight of steps and pushed open Bill's door. He was sitting behind a stack of afternoon papers on his desk, a pair of scissors in his right hand. Although his office only had one small window and Bill was wearing a white-on-white shirt, a brown bow tie, and a double-breasted brown suit, he looked cool. Always a dapper joker, his thin hair was combed back over his almost bald noggin, and he had that youngish look to his puss, like he never had to shave. Except for putting on a little weight and losing a lot of hair, he hadn't changed much in all the years I'd known him.

Looking up from his newspapers, he said, “Hello, Marty. I didn't forget you, I'm busy.”

“I see that,” I said, sitting down in the other chair in his drab office. “You reduced to cutting out paper dolls?”

“You hear the news?”

“Yeah. I heard about all the news I can take for today.” I grinned at him. “So what's new?”

He shook his head slowly. “Marty, I'm in charge of the Detective Squad here. It don't look right for you to be busting in without...”

“If I hadn't busted into a lot of places when we were partners, you'd still be walking a beat now.”

“Maybe,” he said softly. And smugly, I thought, as if thinking, But I'm a lieutenant now and you're just a hotel dick in a fourth-rate dive. “But you know how it is, I have to... well... keep up a front of authority around here.” He waved his hands in the air, as if shoving something aside. “What I mean is, this is a police station, not an old-pals club.”

“Looks kind of clubby to me, Bill,” I said. “Way all these cops off duty wear sport shirts sticking outside their belts. I remember when you had to dress when going off duty.”

“The shirts are cool and they cover a hip holster. That's how the shirt idea started, down in Cuba. Always having revolutions and the lads wore these shirts over their hips to hide the guns they were sporting.”

“Sorry I never went to Cuba. They say the fishing is great down there.”

“What the hell we talking about Cuba for?” Bill jabbed a pile of newspapers with his scissors. “It's the damnedest thing, Bochio swore he'd get Cocky, said it a dozen times we know of, yet the sonofabitch has been in Miami for two weeks, locked in a hotel room with his lawyers. Break that alibi!”

“How's Marge and the girls?”

He put the scissors down and stared at me like I was nuts. “They're fine, except Selma has a virus. Look, Marty ...”

“I remember Selma, she's the youngest. Had blond hair, didn't...?”

“Look, Marty, I'm busy—busy on a murder, so if all you dropped in for was to ask about Marge and the kids, okay, I'll tell them you asked. Now, let me work. Whole damn force is upside down on this one.”

“Which one?” I asked, considering making a crack about Bill's pay-off—maybe he thought I came with dough. But he was very touchy about it, blew up if I even talked about it.

Bill sighed. “Wish I was like you, could just ask 'Which one?' Thought you said you heard the news? They found Cocky Anderson's body up in the Bronx this morning, with a .38 slug through his left ear. You know what that means?”

“What?” I asked as if I cared.

“When Bochio first started out as a strong-arm punk, he ran with a gang that used a slug through the left ear as their trademark for people who knew too much. Also, it's an open secret that old Albert swore he'd get Cocky after the jerk made a pass at Bochio's daughter—tried to rape her is the way I heard it. Should be an open-and-shut case, only nothing shuts, nothing even moves. Damn, a tough one has to break in a hot spell like this—I was set to drive the kids up to Orchard Beach this afternoon for a swim.”

“If he was killed in the Bronx, where do you come in down here?”

“Your brains die when you buried yourself in that hotel? Marty, you know Cocky Anderson had 'interests' on the docks here. For the love of tears, I have every man I can get my hands on out snooping, canceled all vacations.”

“Bochio ain't no hood, and anyway he's been in Miami as you said. Ask me, he's out of the picture. Even that daughter angle is bunk. Cocky was getting too big for the syndicate and they took him out. But the hell with that. I didn't come to talk about rats and punks.”

“Just what did you come about, Marty?”

“Oh... nothing special. Just dropped in to talk.”

“About what?”

“What do you mean, about what? Bill, you're the oldest friend I got. Can't a guy drop in to chat with a buddy?”

“Marty, are you sick?”

“Why? Do I look sick?” I asked, and couldn't stop my voice from shaking.

Bill stood up. Except for the little pot belly he was as lean and wiry as ever. “Marty, I don't like to give you a short answer, but I'm up to my eyeballs in work and you breeze in and talk about Cuba, then about the wife and girls, and then you just want to talk. Damnit, Marty, the pressure is on me, real pressure. Some other time we'll talk about old times.”

“All right, Bill,” I said getting up. “I didn't know you were so busy. Matter of fact I did drop in to talk about Lawrence. He wants to be a cop and I don't want him to have a bad time of it because of me.”

Bill sort of groaned and sat down again. “Don't talk to me about these auxiliary cops. They're driving us nuts.”

“Why?”

“Look, if you ask me this is all a lot of crap—if they think New York City might be bombed, then build air-raid shelters, real shelters. In a real bombing what the hell good will a batch of jokers in white helmets do, or all these drills and the rest of it? Ask me, it's just to keep the people on edge. But nobody asks me. The point is some boneheads downtown made a mistake assigning these tin cops here. This is a water-front section. They belong uptown where things are quiet. Don't worry, they won't be here long.”

“I thought they had their own setup?”

“They do, up to a point. They got some stuffed do-gooder that's a major or some damn thing in charge of them here, and he's such a strutting jerk, somebody is due to clip him. Most of them are crackpots anyway.”

“Lawrence is a bit cop-happy, but otherwise he's a serious kid.”

“Marty, I'm not saying they're all jerks, but you know what happens when you get volunteers. Everything is tossed in, including the bottom of the barrel. For every sincere kid like Lawrence, you get a dozen uniform-happy characters who are only looking for a chance to get away from their wives, walk around looking important.”

“Me, I don't think there will be a war, but you can never tell. But to get back to Lawrence, watch out for him.”

“I will. He's an intelligent kid.” Bill looked up at me. “Since when did you get so fatherly over him?”

“Since last night. He wants to be a cop, a real one, and I have a hunch he's eager beaver enough to build himself up, pass the exams. All right, with my name he's starting with two strikes and I don't want him to do anything that will make him look foolish now, when he's on this volunteer-cop kick. Last night he was all excited about some crazy butcher and a phony holdup.”

“I know, he came to me with that. He's green and full »f too much pep—thinks he has to prove himself, live up to the Bond name, all that. Don't worry—as an auxiliary there isn't much of a jam he can get into.”

“He can make a false arrest, like he almost did with that wacky meat chopper. Bill, he's a silly kind of kid and well... kids today can't take care of themselves the way we did.”

“Bull. Marty, the kids today are a lot smarter and tougher than we ever dreamed of being.” He stood up again. “Don't worry about him. Couple of weeks and he and the rest of these tin badges will be way uptown, putting in their hours directing traffic, or something. While he's here, I'll keep an eye on him. Marty, when this Anderson mess blows over, I'll have you out for supper some night and we'll talk.”

“Marge would sure love that; she could never stand the sight of me. All right, Bill, don't call me, I'll call you,” I said, and walked out. I heard him say, “Now, Marty, I told you I'm swamped ...” as I walked down the stairs.

On the way back to the hotel I had a sudden longing for watermelon and stopped in at the corner coffeepot. I told the old-bag waitress to give me a double hunk and she asked, “What you doing, Marty, eating for two?”

“That's it.”

She thought it was funny and showed me all her bad teeth in a laugh. “Something as big and ugly as you pregnant!”

“Honey, you don't know how much pregnant,” I told her.

I washed down the bad taste in my mouth with a couple of glasses of iced coffee and I was belching before I reached the hotel lobby. Lawson nodded at the office behind him, said, “Mr. King is quite upset over that rug. He wants you to call him.”

“Tell him I couldn't care less,” I said, walking past the desk and into the hallway that took me to my room.

There was no sense in stalling. I locked the door and took off my shirt, tie, and shoes—to be comfortable—then I sat down and wrote a short note to Flo telling her about my gut. I didn't know why I wrote her, she wouldn't give a damn. But then I had to leave some sort of note.

I got out my Police Special. A gun can be the most beautiful or the most ugly thing in the world—depending upon which end you're looking at. Right now it looked ugly as hell.

I sat on the bed and put the muzzle in my mouth, tasting the oil. In a few seconds King would have another rug to get himself in an uproar over. For some reason that seemed funny to me.

For the first time in days I smiled—if you can smile with a gun between your teeth—as I pushed the safety off.

Two

At five after ten that night Dewey pounded on my door. I was in a drunken haze—I'd knocked off over a pint in an effort to get up courage and as usual liquor had let me down; all that happened was I went to sleep for a few hours.

I stumbled out of bed and never felt so awful, worse than when Art told me I had cancer—for the first time in my life I knew I was a phony, a damn coward.

I couldn't understand it; I'd risked my life plenty of times without a thought. I'd even played Russian roulette once when I was young and well crocked. “If you're not afraid to die, then there's nothing to be scared of” was the motto I'd lived by, yet when my own personal chips were down, I didn't have it—I didn't have it at all.

All right, if I didn't have the guts to do it myself, I'd have to figure out some way of getting killed, because I sure wasn't going to take the slow torture of cancer. It wouldn't have been so hard to stop a bullet when I was on the force, but now... Who the hell bothers shooting a house dick? A lousy...?

Dewey knocked again, said softly, “Marty, the cop is here, your son.”

“All right, all right.” I went to the bathroom and washed out the taste in my mouth with tooth powder, ran some water over my face and hands. I slipped on my pants and opened the door. Dewey asked, “What's the matter with you? I been buzzing all night.”

“I'm sick.” The cold water had done the trick, I was pretty sober.

He looked past me and saw the empty pint beside my bed. “So I see. You're a fine one, not even giving me a taste for my cold. Things went smoothly tonight.”

“Yeah?” It was a welcome shock to realize from now on I didn't have to give a damn how anything went—except to figure out a way of dying before the damn cancer got me on a slab.

“Business been pretty fair with the girls. Must be due to it getting a little cooler tonight. What about your son? Don't help things having a cop hanging around the lobby.”

“You mean he's in uniform?”

“No, but I know he's a cop. I don't like it.”

“Forget him—send him in.”

I kicked the fallen soldier under the bed, straightened up the sheets a little, waved a towel around to get the sweaty stink out of the air.

Lawrence came in, said, “The character out at the desk tells me you're sick.”

“Heat got me down. Take a chair.” The kid had a crew cut like Lawson, was wearing a polo shirt and slacks. He looked better out of uniform. Except for his scrawny neck, he had a neat build for his size.

He slapped my bare stomach. “Still got your rubber tire. Remember how you used to tell about the times you were in the ring and the other guy would waste his punches on your pouch, leave your chin alone, and how you could take it down there all night long?”

I said yeah and looked down at my gut, the fat and the muscles under that, and now under the muscles a lousy tumor waiting like a booby trap. I sat on the bed, changed the subject with, “What's new on Cocky Anderson?” I winked at him. “Speaking of remembering, when you were a young snot you clipped out crime stories like other kids did baseball pictures. What's your dope on this one?”

He winked back. “Okay, keep on riding me, Marty. All I know is what the papers have. Medical examiner claims Anderson had been dead for about twenty-four hours when some youngsters stumbled on his body. The papers say Anderson hadn't been around his usual spots for the last few weeks, but then he'd been a difficult one to keep tabs on. That's about all. Oh yes, they think he was shot someplace else, then dumped in this lot.”

“Bochio still shouting off his mouth down in Miami?”

“Sure. The papers have him saying he's sorry somebody beat him to the killing. Bochio's daughter is reported to have collapsed. I suppose you knew Anderson? What is—was— his name, Rocky or Cocky?”

“Both. He came out of the army a pork-and-bean middleweight, but smart enough to give up the ring. Then he became a muscleman, had some luck—sort of a throwback to the old-style trigger-happy hood, except he used his fists. That's when they started calling him Cocky Anderson, way he used to swagger around. For a time he was a syndicate cop, then branched out on his own, bucked them. He was rough—and dumb.”

“What's a syndicate cop?” the kid asked—like a kid.

“A punk a little more rugged than the other creeps, keeps them in line. You all out to solve the big murder too, Lawrence, like a movie dick?”

He sat down on the bed beside me. “Gather you don't think much of me as a prospective policeman, do you, Marty?”

“What I think is anybody is a fool to become a cop. Talked to Bill Ash today. He says you volunteer coppers get in his hair, that you're a bunch of screwballs,” I said, wondering why I was baiting the kid.

“I wouldn't go that far; we're a fair sampling of any bunch of volunteers. You have the sincere fellows, some jerks, and a few angle lads—wanting to get in on the ground floor, hoping this will be a good thing, moneywise, in time. For the higher-ups, there are some good-paying jobs, the usual political plums.”

“Think your night stick will beat an atomic attack?”

He grinned again. “I know what Lieutenant Ash thinks, and in a way he's right—if we really expect a war we should build shelters now. But then, even a little preparedness is better than none at all. Hell, Marty, you know why I'm in it—gives me a taste of being a cop.”

“Are you still working on the big liverwurst mystery?”

“Yes. And I'm convinced I've come up with something. I came to tell you about it. I went up to see where Lande lives. He seems to have come into money recently. The janitor of the building was the talkative type, told me Mrs. Lande has blossomed out with a mink coat and her own Caddy. All within the last month. Before that the janitor claims he had to remind them to come up with the rent.”

“You fool, the janitor will tell Lande you were asking about him and he'll complain downtown and they'll take away your tin badge, maybe even arrest you for impersonating a policeman!”

Lawrence gave me a wise smile. “Marty, I'm studying to be a lawyer, I'm aware of the law. I told him I was an insurance investigator making a routine check, and to keep it quiet. The point is, you see what all this proves.”

“I don't see nothing.”

“It proves he could have been robbed of the fifty grand.”

“And the two clowns who are supposed to have done it returned it a few hours later with a sorry-opened-by-mistake note!”

Lawrence looked at me like I was backward. “Once we establish that it is possible he had the money, it gives credibility to his original story—that he was robbed. By the way, did you read in the evening papers where two young hoodlums from the West Side were shot to death in a gas-station holdup outside Newark early this morning?”

“I didn't read that, Mr. Holmes. In fact I haven't read the evening papers. But what docs it prove?”

“I don't know that it proves anything yet. But struck me it was a coincidence they were both shot through the heart, one bullet each. Fellow has to be quite a marksman to do that in the heat of a stick-up. Another thing, no witnesses.”

“There'd hardly be any witnesses early in the morning. When would you expect them to hold up the joint—when it was crawling with customers?”

“Merely a thought,” Lawrence said in that precise way he had of talking. “Two young punks rob and return fifty grand, and a dozen hours later two young punks are shot dead. Seems to me the only reason they returned the money would be because they were frightened—frightened of somebody powerful enough to kill them. According to the papers, and I read them all, their description fits the one Lande first gave me of the holdup men. Of course that's a general description. I asked the Newark police to let me see the bodies—they refused. Oh, yes, the gas-station owner has a record, did time for assault many years ago. But he has a permit to carry a gun and he...”

“You'd better cut this, kid, before you hook up every crime in the country with a robbery that never happened to your batty butcher. I suppose you saw the butcher, asked him to identify the bodies?”

The boy actually blushed. “Why, yes, I did suggest it. I dropped in late in the afternoon, after I read about the killings. You recall I said he was so nervous yesterday? Well, today he was all corny jokes and full of good cheer. Wanted to give me a thick steak. But when I asked him, as a citizen helping the cause of justice, to go over to Newark and look at the bodies, he blew a gasket. Shouted I was trying to make a sick man have another stroke, told me to get out.”

“'... a citizen helping the cause of justice'... Goddamn! I— Lawrence, you're one for the books, the joke books!”

“What's the joke? If he was really interested in helping ...?”

“Lawrence, first off, nobody likes to look at a couple of stiffs, much less ride all the way over to Newark to do it. Secondly, since the butcher denied there ever was a holdup, why should he agree to look at a couple of dead punks?”

“There're two sides to every coin and the reverse side of this one is that Lande is scared, that he knows the two dead men are the same ones who robbed him. Okay, laugh if you wish, but that's my opinion of the case. I think there's something in all this. Tomorrow I'm going to have a talk with Lande's driver.”

“I hope you're not giving this cock-and-bull story to Bill Ash.”

“He's too busy on the Anderson killing to see me.” He stood up. “Dot was glad I talked to you yesterday.”

“Was she? Has she changed much?”

“No. At least not that I've noticed or...” He saw my gun on the dresser. I'd forgotten all about the lousy thing. “What are you doing with this—planning to kill somebody?”

“If I say yes, will you tie me up with your liverwurst tycoon? That's what guns are for, mostly to bluff and sometimes to kill—if you can.”

He went over and hefted the gun, balanced it with one finger under the trigger guard. I said, “Forget that and tell me more about Dot.”

“She's the same. We don't have guns. Marty, is this your old gun?”

“Aha.”

“Sure seen plenty of action. Where are your citations, Marty?”

“I don't know, probably around someplace. You medal-happy?”

He opened the top drawer, put the gun in. “Marty, please stop treating me like the village idiot. I want to be a good cop—if I can—and a live one. If I find anything new from Lande's driver, I'll drop in tomorrow night, if you don't mind.”

“Lawrence, I told you I don't mind. And keep away from your butcher—mind your own business.”

“We differ on what is my business. But I'll be careful.”

I shrugged. “All right, and if the joker offers you a steak again, bring it here if you don't want it.”

“Petty bribes, the curse of law enforcement,” he said, mocking me.

“You ain't kidding—hold out for the big ones,” I told him, going over to my desk to make sure the note I'd written Flo wasn't in sight. “Like a drink?”

“No thanks. I have to get home, early class tomorrow.”

I walked him to the door and as we shook hands he said, “Leave the bottle alone, Marty. Get some sleep.”

“Think you're big enough to be giving me advice, kid?”

“I don't have to be big to see you look tired. So long, Marty.”

When he left I felt lousy. Lawrence was a jerk, but a nice jerk, one of these serious kids, and not as silly as he sounded. Only that kind gets hurt as bad as the wild ones. Damn, my own son comes in and all we can talk about is killings and stick-ups. I should have talked to him more—but about what? He was a stranger to me. That was the damn trouble —I'd lived all my life among strangers.

I was hungry and my gut hurt. The quiet of the room gave me the spooks. I was lonely. I turned on my table radio and listened to some jazz, but that didn't help. I phoned Dewey, told him to send Barbara in.

“Now? It's early—can't you wait?”

“Send her in and shut up!” I unlocked my closet and took out another pint. I had four cases stacked there—late at night when a guy wanted a bottle real bad, a pint brought five to ten bucks. I never made much on liquor though, because I was always my own best customer.

I opened the bottle, washed out two glasses, lit a cigarette.

After a few puffs the smoke tasted sour and I threw the cigarette away, chewed some mints.

When Barbara knocked on the door I told her to come in, and she asked, “What's up?”

“Nothing.”

“Is that so?” she said, giving me a wise look.

“It's so. Want a shot?”

“Small one. Hear you ain't feeling so chipper.”

“I can't sleep,” I said, pouring her a shot.

“It's the lousy heat.” She put the drink down with one fast gulp, sat on the bed. “Come on, schoolboy, I'll relax you.”

“Cut it. Let's talk. What do you plan to do? I mean, hell you know you only have another few years left in this racket, then what?”

She jumped to her feet. “What kind of talk is that?”

“Friendly talk. You and me, we don't have to kid each other. Let's talk about something else. Where do you come from—a farm?”

“Are you nuts? This is the best time of the night. I can't sit here and bull with you while the other girls are turning all the tricks. I have to make...”

“Let your pimp buy his new Caddy a day later!” I said, reaching over and slapping her. I didn't hit Barbara hard, but her left cheek went dead white, then a flaming red as she fell on the bed and began to sob.

I sat beside her, held her in my arms. “I'm sorry, honey. Sorry as hell.”

“What's got into you, Marty?” she asked, crying into the gray hairs on my chest. “What the hell's the matter with you?”

“I'm on edge, can't sleep. I... Look, I'm real sorry. You know how things is with you and me. I got no use for those other whores, but you...”

“Don't call me that!”

“Why not? You are a whore and I'm an ex-cop turned pimp and... Stop bawling. Told you I'm sorry. I lost my head.” It felt pretty swell holding her, feeling her crying. Somehow it made me feel alive.

She pushed out of my arms, dried her face with a sheet “I can't stand a guy hitting me. And you...”

I put my hand over her mouth. Her face looked tired and drawn, played out. “Barbara, how many times must I tell you I didn't mean to hit you?” I put my hand in my pants pocket, took out a bill. Happily it was only a five spot. “If I give you this will you buy yourself some perfume, stockings, or something—keep it out of Harold's mitts?”

“I can't hold out any dough on him. You know how funny he is about that. And you don't have to pay me...”

“I'm not paying you. This is a present.”

“Then buy me some perfume—give me the bottle not the dough.”

“All right.”

She got off the bed, looked at herself in the mirror. “I got to go now, fix my face up.”

I walked her to the door and then took a stiff drink—had a hard time keeping it down. The news came on the radio, all about the Anderson killing. I shut it off and walked around the room for a while, trying to think. I opened the drawer and stared at my gun—knew I couldn't do it. It was crazy—there were plenty of mugs around who would be hysterical to plug me if I told them to, only how do you tell a slob you want him to kill you? How do you look? What do you say? What...?

The door opened and I slammed the drawer shut. Barbara came in. “I got some sleeping pills here. Two—enough to knock you out.”

“I never fooled with goof balls.”

“Won't do you no harm and will make you sleep like a baby,” she said, filling a glass with water.

I washed the pills down. “How long before they work?”

“Few minutes, if you don't fight them. Lie down and relax.”

I sat on the bed and wondered if this might be it. Take a box of the junk and slip out of this world. Only somebody would be sure to wake me, or find me, in the Grover. I could get a box and go to another hotel where...

“Feel sleepy?”

“Not yet. And stop watching me like you thought I was getting ready to explode or disappear.”

“You got to stretch out, meet the pills halfway.” She gave me an odd little smile. “You're a crazy guy, Marty. Are you afraid to kiss me?”

“Hell, no,” I said.

I gave her a big hug and kiss, glad I had the mint taste in my mouth. She flicked her tongue at the tip of my nose, said coyly, “That was sweet, Marty,” then she kissed me hard, threw her tongue halfway down my throat. When she pulled away she gave me a smart grin, said, “We're alike. I'm in a lonely business, dealing with lonely people who want to get rid of me fast as they can. A cop's the same way— nobody wants him except when they need him. For a time your being even an ex-cop made me uneasy.”

“What are you, the wise old bird tonight?”

“Sometimes I like you, like you a lot. Now hit the sack.”

I stretched out on the bed and Barbara waved from the door. I told her, “Fix the door so it will lock.”

She did that, waved again, closed the door. I loosened my belt, reached over and turned off the light. And waited, wondering if I was going to dream of Mrs. DeCosta again. I started thinking about Lawrence.