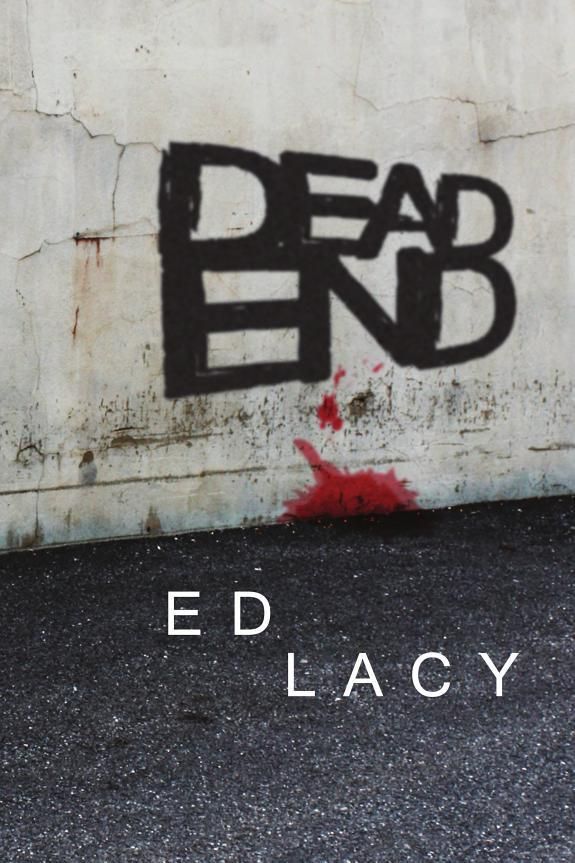

"Dead End" - читать интересную книгу автора (Lacy Ed)

|

Dead End

Ed Lacy

This page formatted 2007 Blackmask Online.

http://www.blackmask.com

1—

2—Nate

3—

4—Elma

5—

6—Shep Harris

7—Judy

8—

9—Betty

10—

11—

12—

13—

14—

Be careful how you live. Not thoughtlessly but thoughtfully. Make the most of your opportunities for the times are evil.

5:15,16

1—

Doc was stretched out on the cot, fooling with his .38 Police Special. It was an old canvas army cot like mine and soiled by I hate to think what. And of course minus sheets or blankets. Not that we needed them in the muggy room: What we needed was a little clean air.

I watched Doc for a moment. Doc the sharp dresser, Mister Dapper himself. Now he looked seedy. That wasn't like Doc. His suit was wrinkled and tacky, and he had a three-day grayish stubble on his lean face. Even his face was dirty, and his hair seemed ragged. This wasn't like Doc at all. Me, I'm a slob. But at least I was washing every day—using laundry soap for shaving cream. Doc had said he didn't want to use the razor we'd found in the house. But it was a new razor. I don't know; Doc's being so sloppy was beginning to make me uneasy.

Or perhaps it was the waiting. The room itself. The room was so small and crummy it was starting to spook me. Two cots, one broken chair, cracked walls, one naked light bulb. Of course no windows. And bugs. (If this was such and old and unused hideout, what the devil had the damn bugs been feeding on all this tune?) It all reminded me of a cell. Though the only cells I'd ever seen were the detention cells in the precinct houses—and they were luxury rooms compared to this joint.

I turned on my cot and picked up the magazine again. I'd found it under the bed. Dated March, 1951. It was full of coffee stains. Must have been good Java, the color held up for all these years. Of course, maybe it wasn't coffee. For two days I'd been trying to read the dumb stories, rereading the same lines over and over, my mind racing and thinking of a million other things—and I mean

When I found myself reading the same silly line,

“Trying to knock down a few of our friends.” He stretched out again; he said, “They're not bothering us.”

“You look like a bum. Why don't you wash, shave?”

“What for?” he asked softly. “Anybody sees me, a shave will be the last thing they will be thinking about.”

Doc always talked softly. With his slight, slim build, the soft voice, the gray hair, you'd never take Doc for tough. But he could be a cage of apes when he had to. Once we were sent out on a vandalism case; some kids were seen busting the windows of a small church. Doc sat in the squad car while I went out to investigate: Doc was very busy with his paper work—figuring his horses for the next day. The “kids” turned out to be half a dozen teen-agers, all of them over six feet and hopped up on beer. They dropped on me like a swarm of monkeys. Before I could get my fists working I was on the ground, the punks sitting all over me, one of them using my head for a yo-yo. I blacked out for a few seconds. When I opened my eyes again Doc was moving among them very gingerly, his sap in his left hand. He'd bat a kid, clout another with his right fist, kick one in the belly, all the time moving daintily as if afraid to wrinkle his suit. I worked the slobs over myself, and then was examined at the hospital for a possible concussion. We almost got hung on a brutality rap, of all things. Seems they were a basketball team celebrating a win, and their dumb parents sobbed about their “poor boys.” They should have seen them dribbling my noggin around. Anyway, because a church was involved, nothing came of the beef.

“I feel better, shaving every day.”

“The Englishman in the tropics?” Doc asked, smiling faintly, still working on his gun. He was always saying things I didn't understand, as if I didn't know which end was up. “I'll shave when we're ready to bust out of this dump, Bucky. Tough turn, the firing pin breaking on me now.”

I reached out and touched my own gun in its shoulder holster. I was always fondling it. “What's the difference? If we're collared it would be dumb to shoot it out anyway.”

And while I was talking I suddenly turned—out of habit—and looked at the three bulky, old-fashioned suitcases against one dirty wall. Innocent-looking bags, used and worn: You'd never suspect what they carried. I never let the bags out of sight for long. Even while sleeping I'm always waking up to glance at them fondly. But then, you see, I was kind of an underprivileged kid—I never had the opportunity of looking at a million bucks before.

Doc said gently, “You're wrong, Bucky. If we're ever caught the smartest and best move will be to shoot it out, and hope to stop a slug. Prison isn't exactly a gay place for cops. I should say, for ex-cops.”

“You're full of happy thoughts. This damn room reminds me of a cell as it is.”

Doc grinned, showing all those small, sharp teeth he usually took such good care of. “Son, never try to kid the kidder. You're getting nervous. It's understandable. We're gambling with a million dollars. I imagine the odds are at least two to one we won't carry it off. But the bundle is worth the gamble. Or isn't it?” He looked up from his broken gun, hard eyes on me.

I wasn't exactly unhappy about his gun breaking. Not that I didn't trust Doc, but he was a many-sided joker, and most of his sides I didn't understand. I said, “Stop selling me. I'm in.” And how silly it was to talk about being “in.” There wasn't any way out—now.

Doc smiled, turned his attention back to his gun. “Just unwind, Bucky boy. We're in the clear, doing fine.” He pulled a crumpled cigarette out of his pocket, said, “Give me some fire.”

“What's the matter with your lighter?” I tossed a pack of matches over to him.

“Out of fuel.” Doc lit his cigarette, grinned as he tossed the matches back—a looping toss. The matches landed smack in the middle of my face.

Doc reminded me a lot of Nate—always telling me to take it easy when he was showing me how to swim, or fish, or box. Doc had the same competence about him; he was able to do so many little things, just like Dad, although he was not as warm as Dad was.... Now, why was I calling Nate “Dad”? The sonofabitch wasn't my real father.

2—

I guess it was comical. I mean all the street fights I was in because I thought my name was Laspiza and somebody would crack smart about Italians. It was only when I finished high school, was going into the Army, that I really learned I wasn't Nate Laspiza's son. I'd had kind of a hint several years before that he wasn't my real father. But when I went into the service there was the little matter of a birth certificate, and then I found out I wasn't even his adopted son.

Both times hit me pretty hard, but on the last one I nearly blew my deal. To this day I don't know how Mom worked it in grade school, but I was always registered as Bucklin Laspiza, which was certainly a fancy handle. But I was damn proud of it. You see how it was. Mom wasn't much of anything around the house. That is, she was just a mama, kind of sloppy and plain-looking, who did the cooking and washing, nibbled on a bottle in secret, or split a few bottles of beer listening to the radio at nights with Nate. I don't want to give you the wrong impression—Daisy was a good mother to me, the best. When I say she hit the bottle, I don't mean she was a lush, but I knew she was taking a secret nip now and then; and looking back on anything, I suppose it's always the bad things that stand out.

Daisy was good and considerate, and I loved her, but I was crazy about Nate, that sonofabitch. In a way, he was about the greatest father a kid could have. I haven't seen him now in years, never hear from him except for the usual Christmas or birthday cards. But in those days, when I was about ten, Nate was my hero—different from the other men in our neighborhood. In this semi-tenement block, most of the men lived in overalls, but Nate was a receptionist for a big oil company downtown and he always wore a pressed suit. He was like Doc, always a snappy dresser, shaving a second time in the evening, even if he was only going to the movies. Why, he wore gloves and sometimes even spats.

He wasn't a big man, never weighed over a hundred and fifty, but Nate was wiry and compactly built. He had a mild sort of face, not handsome but with an expression as if he found the world an amusing sort of place, a kind of secret joke of his own. It was a joy to watch Nate walking down the street among the grubby-looking men and drunks—the snap to his step. You know, I never saw Nate staggering drunk: Like everything else he did, he knew how to drink. Along about five thirty every afternoon I'd watch for him, his standout neatness, the smile on his lean face, his gloves. When I was eleven I used to sleep with Nate's pigskin gloves under my pillow whenever I could.

There was a big slob of a coal-truck driver who moved into one of the houses with his snot-nosed kids. He usually had a half a load on, was all covered with coal dust, and on paydays might pass out on the tenement steps. He had a bellowing voice, was over six feet tall and lardy—had to weigh about two hundred and fifty. He had a rep as a saloon brawler and looked it. One afternoon his oldest kid tried to say a ball I had was his. I wasn't lying or anything when I insisted it was mine.

You see, Nate paid a lot of attention to me. Most guys on the block had so many kids they treated them all as if they were pests. We were the only family with a single child and both Daisy and Nate gave me a lot of time. Especially Nate. He used to take me fishing and hunting, go to the beach with me, show me how to play ball, how to box, and on my tenth birthday he gave me a set of weights and we would work out together a few nights a week. What I'm trying to say is, with Nate's tutoring I was handy with my mitts, maybe even a bit of a bully, so I had to give this kid a bloody nose to convince him about the ball. It was late in the afternoon, and I'd forgotten about the whole damn thing, when this big slob, the kid's old man, came lumbering up to me. He was breathing whisky and suddenly deciding to play the Big Daddy. He said, “Give back that ball, you stealing little wop.”

“No sir. It's my ball. I'm sure because I got it cheap—there's a bump in the rubber and it bounces cockeyed.”

“Don't give me no Eye-tie lip, just the ball.”

“No, sir. That bump—that's how I'm positive it's mine,” I said, scared stiff but standing up to him. As Nate used to tell me,

So he made a grab for me with one dirty mitt and I ducked under his arm, punched him as hard as I could in his big belly. I didn't hurt him but some of the other men began to snicker. He roared, “Now I'm going to wack your guinea ass, and wack it bare!”

I suppose I was too scared to run. I kept side-stepping his rushes, hitting his stomach—too dumb to smack him below the belt. Some of the women were telling him to stop it, and I remember Mom screaming out of the window to leave me alone. She had a bitch of a temper when she cut loose—even Nate respected it—and I'm sure if she had been able to dress and get down the five flights in time, she would have tore into this lump.

The exercise was sobering him up and when he finally caught me, he ripped my shirt down the back, tore my pants, pulling them down. Maybe he was a queer—he was licking his lips, and I felt his spit on my bare can before he walloped me. That spit hurt worse than the actual lick. Then Nate was pushing through the ring of people. He said in a mild voice, “Get your dirty hands off my kid!” Yeah, he said

The big jerk dropped me. He stood there with his hands down, roaring, “Look what we have here, the Eye-tie dude!”

Rolling out of the way as I pulled up my pants, I watched Nate step in and belt the guy. It was a hard punch and Nate neatly turned his gloved hand as it landed cutting the eyebrow.

His face bloody, this giant rushed at Nate. His idea of fighting was to come in bellowing and cursing, swinging like a gate. If he'd ever got to Nate he would have crippled him. But Nate knew what he was doing, dancing in and out like a cutie, those tan gloves slicing the big face. Why, Nate's pearl-gray Homburg never even came off! And in a matter of seconds he had the lump's eyes puffed shut, blood streaming from his nose and flabby mouth. Then Nate started working on the heaving belly, and after another minute the big slob was sitting on the street, puffing and actually crying with shame. Nate said, “If you ever lay a hand on my kid again, I'll give you the full treatment. Come, Bucky. Daisy has supper waiting.” And Nate without a mark on him, hardly breathing deeply.

I was one proud and happy kid as we walked through the crowd. And those gloves were so bloodstained Nate could only use them for fishing. Daisy didn't want me to sleep with them, but Nate said it was okay. When I grew bigger I wore them until they fell apart.

Nate was so many things. Except for going to work, most of the people never left our block. But Nate and I went every place. He was a great cook and on picnics he would build a fire and broil the fish we'd caught. Or split hot dogs and stuff cheese and bacon and all kinds of spices in them. Or roast whole ears of corn, husks and all. Often Daisy went with us but usually she was too tired. Even now I can recall the time Nate killed a rabbit on the run with a stone, roasted it on a spit—man, what a meal that was! I'm not lying about that, Nate was a hell of a pitcher. He once played semi-pro ball. Sometimes he'd pitch for a local sand-lot team and everybody would ask him why he'd never made the major leagues. Nate knew everything about the game, would often take me to a ball game and practically call every play before it was made. He told me not to tell Daisy about going to ball games, it made her sick. I didn't understand about that until I left home.

Nate was all-around. Whenever one of those professional pool players, one of those masked marvels sent around by the pool-table outfits, played at the corner pool hall, they would ask Nate to take him on. Of course Nate never won but it was always a close game. And when his office had their yearly outing, Nate would take me and Mom, and we'd watch him win the sack race, or even the hundred-yard dash against younger fellows.

The first I knew Nate wasn't my real dad was when I was thirteen and he went away for a week end to attend his mother's funeral. I knew Daisy's folks had died long ago, although I'd never seen them. She had a sister I saw once when I was a kid. Nor had I met any of Pop's people, and when he went away I kept asking Daisy why I had never seen or heard of this grandfather. She told me it was because they lived way out west. Daisy really hit the bottle that week end. I had to put her to bed. When Nate returned Sunday night they had an argument in their bedroom. On account of Mom being crocked I'd been sleeping lightly, so I awoke to hear her say, “Hon, he's getting big now, and asking questions. Why don't you adopt him?”

“No. Let's not go into that.”

“But I know you love Bucky. Why put him through this? He isn't to blame.”

“Daisy, I've had a rough week end. You look like you've had one, too. Let's not talk about it. I'm providing for him, doing everything I promised.”

“But why can't you go all the way?”

He didn't answer and then I heard her sobbing and Nate said, “Come on now, Daisy, dear. You know I've done the right thing. Please don't cry.”

I tossed on my day bed in the living room for the rest of the night, was sick in school the next day thinking about it. That night, when we were listening to the radio and Daisy was in the kitchen finishing the dishes, I asked him right out. “Nate, are you my real dad?”

I was a little hysterical. He glanced toward the kitchen, whispered, “Bucky, do you know what a real father is?”

“Well, he's... a father.”

“A father is one who feeds his boy, dresses him, takes him out, cares for him. I dress you better than any other kid in the block, take you more places, don't I?”

“You bet. Then you are my real father?”

“Keep your voice down. I just answered that, didn't I, Son?”

“Then what was Mom crying about last night?”

He grinned and poked me on the arm. “You know women; sometimes they get high strung. Tell you what. Tomorrow is Friday. If Daisy don't want to go to the movies, I'll take you bowling. It's a nice sport and you've never tried it. And you forget Mama's crying—talking about it will only make her nervous. You know how she gets at times. Okay?”

I thought he meant she was unwell. He took me bowling on Friday and won a carton of cigarettes for making high score of the week.

When I was just turning eighteen and in my last term of high school, Daisy began to have sick spells, keep to her bed a lot. She was always skin and bones, although I was surprised when I once came upon a snap of her as a young girl—she had a slim but solid figure. I came home one afternoon from football practice—I was always a second-string tackle—to find her on the kitchen floor. I set up such a hollering the neighbors came running and soon an ambulance doc. He said Daisy was dead—as if I didn't know—that her heart had given out. Nate took it bad, crying all night and staring at the wall for a few days. Of course, I felt bad at losing Mom, but it really didn't change my life much. After the funeral things went on as before, except I did the shopping after school and Nate cooked.

I was almost as big then as I am now, weighed in at a hundred and seventy-four pounds, and was trying to be an amateur boxer. Nate was my manager, trainer, and second, and after Daisy's death we worked hard at it. Three nights a week I'd train at a gym the pros used during the day. I had a few fights, winning them all. They weren't easy fights and I didn't see any future in throwing leather. But it made it easier for us to forget Daisy, gave both of us a charge, me in there fighting, Nate leaning on the ring apron, shouting advice. Nate and I were closer than any father and son.

When I graduated school a few months after the funeral, Nate gave me a swell watch, a wrist watch with the picture of a pug, the hands of the clock being his arms. I still have it. The night of my graduation he took me out for some real Japanese food and a couple of belts of rye, telling me how sad it was Daisy didn't see me get my diploma, how I must go to college, maybe even get an athletic scholarship. When we returned to the flat there was a check for three hundred and fifty dollars in the mail for Bucklin Penn. There was one for Nate too, for the same amount. He said, “From your dear mother's policy.”

Never having had that much money before, I was too delighted to think straight for a moment. Then I asked, “But what's with this Bucklin Penn tag?”

Nate was unrolling my diploma, which he was going to have framed the first thing in the morning. I was astonished to see the same name on the diploma—Bucklin Penn. I asked, “What is this, Dad? Why isn't Laspiza printed there?”

Nate had the same look in his eyes as when he was getting ready to make a tough pool shot, or pitch his fast ball. “Because your name

“That was Mom's maiden name but my name is Laspiza.”

“No it isn't,” he said quietly. “That's why I arranged for your correct name on your diploma. Son, it's time you knew I'm not your actual father.”

“Well, who is?” I asked, my voice a croak. I was all mixed up; him telling me that and calling me

“I don't know. Daisy would never tell me. Truth is, I never asked.”

Now, Nate had a good sense of humor, sometimes was given to mild practical jokes. Like once I'd saved up for a model plane they were advertising on a corn-flakes box. I gave Nate the letter with the money to mail on his way to the office. That night he came home with the plane-kit box, addressed to me, stamped and everything, said mail service was sure fast these days. It took me a few days to realize he had bought a kit in a store, had his company's mail room fix it up.

Feeling like I'd stopped a gut wallop, I asked, “Nate, what kind of a gag is all this?”

“How I wish it was a gag, Bucky. This is going to be rough, for both of us, but I have to tell you something I wanted to say long ago, but Daisy wouldn't let me. I kept telling her it was a mistake not to tell you....”

“Tell me what?”

“You're almost a man now, Bucky. You can understand this. Daisy and I grew up together in a small town not far from Gary. We were sweethearts from the day we first saw each other. Her folks weren't too keen about having me in the family because I was Italian. Well, her parents were killed in an auto accident when Daisy was fifteen, and she came to live with us. We were to be married when she was eighteen. After about a year or so, she began working as a waitress in a combination bar and restaurant. My people were very strait-laced, you understand. They didn't want her working. But Daisy liked being independent, and she wasn't working nights—when the bar might get rough—only during the afternoons. I don't have to tell you about sex, Bucky; we went over that a few years ago. What I'm trying to say is, I never touched Daisy, although we both wanted it. You see, we agreed we would wait.”

He stopped talking for a moment, and when he continued his voice was shaking like a ham actor's. “Daisy was going to be seventeen on August twenty-fifth. I was nineteen and that summer I got an offer to play semipro ball up in Canada. It looked like my big chance. In July—July eighth in fact; 111 never forget that date—my father wrote that I should consider Daisy dead—they had kicked her out of the house. I left the team and rushed home. She was a month pregnant with you. Some louse had fed her a few drinks, raped her. She had been ashamed to even go to the police. We were married that same day, and came east. I promised her I would raise you like my own son. Bucky, you know I've kept my word. I intend to help you through college, keep on being your best friend and—”

“Best friend—you

“No, I'm not. A fact is a fact.”

“But you've been a father to me for almost eighteen years. Why didn't you... don't you... at least adopt me?”

“I can't do that, kid.”

“Why?”

“Well—I just can't. You're better off with a name like Perm. A good American name that—”

“Nate, Nate, don't bull me! Why can't you give me your name?”

“What's in a name?” he asked, then turned away and added—almost painfully, “Bucky, don't ask me why.”

I spun him around. “But I'm asking!”

“Look... I never told you this, of course, but—I'm wanted by the police.”

“Since when? What for?”

“I don't want to talk about it. But it's true.”

“I don't believe it. Why, you're so honest you wouldn't keep the three bucks in that purse you once found! What—”

Nate was suddenly full of cheer. “Still time to make a late show downtown, kid. Come on. What difference does it make if you're called Smith, Brown, or anything else? A handle is merely a label and I've raised you to be a fine young fellow. We'll take in a show and forget it.”

“Sure, just forget a trifle like finding out I'm a bastard!” I screamed, running out of the apartment.

I had the check with me and managed to cash it. Then I did a real dumb thing: I got crocked in the neighborhood. Being a pug and a football player, I was sort of a big deal around the block, and plenty of the better-looking babes kept asking me to take them out. Elma wasn't one of them. She was a big plump girl of about eighteen and her claim to fame was her constant use of a four-letter word. Okay, it may sound jerky now, but then it was kicks to hear a girl talk like that. Guys took Elma out to hear her dirty jokes, and when she got mad Elma would repeat that four-letter word over and over, so the fellows would try to get her boiling. That wasn't so simple, for Elma was very easygoing. Don't get me wrong; I knew she never went all the way. But several times she let me run my hands over her. Elma never made any bones about it: She went for me in a big way. All I remember about that drunken night was me telling everybody my name wasn't Laspiza, like a fool, and Elma hanging on to me, saying, “Penn is a nice name, Bucky. Why, maybe you're descended from the famous William Penn. Jeez, you got an arm like a rock. Make a muscle for me, Bucky.”

Nate finally found me around two in the morning, took me home. For the first time in his life he took off a few days from his job, stayed with me. The crazy thing is I might have got over the shock if I hadn't stupidly broadcast the fact I was a bastard. It was a bit of choice gossip. I knew guys were snickering behind my back, and the girls avoided me. But Elma was with me as much as possible.

It got so I couldn't stand the damn block and one day I went off and enlisted in the Army. This was about a year before Korea. Nate was heartbroken—which gave me a kind of dumb satisfaction. He told me, “You've made a bad mistake, Bucky. You should have gone to college. A man isn't anything today without a college degree. If I'd gone to college do you think I'd have ended behind a reception desk, grinning like a dressmakers' dummy? I been with the company for over fifteen years and every time there was an opening, a chance, they passed me by for a college kid.”

“So what? I would have been drafted in a few months anyway.”

“I suppose so. Take care of yourself in the Army, come out with a clean record. This might work out for the best, maybe you can still go to college, on the G. I. Bill when you get out. It will be good for you to get away—this Elma isn't for you, Bucky. She's older and a—”

“Nate, you were about twenty-seven when World War II was going. I guess having me around kept you 4F.”

“A busted eardrum kept me out.”

“I bet you told them I was your real son then. I bet!” I said, leaving the house for a last date with Elma.

I breezed through basic in a southern infantry camp. Nate wrote me regularly, sent me shaving kits and all the dopey things you send a soldier, but I never answered him. Whenever I got a leave I spent it drinking and fighting bootleg pro bouts in a nearby big city. I was stationed in Texas when Korea broke and we were sure to be sent over. I got a two-week leave and a plane ride back home. I really didn't go “home,” I took a room downtown. The first thing I did was insist upon Elma spending the night with me. The deal with me was, I couldn't think of anything but Nate not being my old man. I guess it became an obsession with me. I thought about it all the time, in camp, in the ring, even sleeping with Elma. The thought kept rattling around in my head. When I could look at it calmly, I knew he had done the right thing by Daisy. Most guys wouldn't have. What it must have meant to Nate to give up pro ball, his big chance. And to leave his family. But what kept eating at me was,

I was liquored up most of the time, not much of a feat as I'm hardly a drinker; a few shots does it far me. When I had three days left of my leave, I went up to the apartment late one afternoon, knowing Nate would be home from work by then.

When I opened the door he was making supper, wearing an old smoking jacket. Nate never slopped around the house in his undershirt. He said, “Hello, Bucky. I heard you were in town. Looks like you've put on muscle. Soldiering must agree with you.”

“I can take it or leave it. I... uh... meant to come by sooner but I had a few stops.”

“I can smell them. Want supper?”

“No.” I staggered a bit trying to make the table. “I want something else, Nate.”

“Broke? I can let you have—”

“I want you to call me Bucky Laspiza. I want to hear you say it right now!” I said, the anger building up in me so strong the words came blurting out.

Nate gave me a “fatherly” smile. “Come on, now, Bucky, you're crocked. Why do you let that worry you so? You know the old line about what's in a name? I think—”

“Nate, stop stalling. You're going to call me Bucky Laspiza, or I'm going to make you. I been thinking about it for weeks now. You've called me 'Son,' and 'my kid,' and 'Bucky,' but I can't ever remember you calling me Bucky Laspiza!”

“Aren't you being silly?”

“Nothing silly about it to me!”

“Bucky, suppose I did say what you want—what difference would it make?” he asked, coming around the kitchen table to face me. I'd worked out with him enough to tell from the way he had his legs apart that he was set to hit me. I wanted him to. I guess what I'd really been thinking in the back of my noggin all these months was that I hated Nate so damn much I wanted to kill him.

“Don't soft-sell me, Nate. It will make a lot of difference to me. Just call me Bucky Laspiza, Nate.”

“Want me to call you mister, too?” he said, wetting his lips nervously.

“The hell with mister. Call me by my name!”

“Certainly. Hello, Bucklin Penn.”

“Goddamn you, Nate, you're going to call me Laspiza!”

“I can't. It isn't your name.”

I started for him. He was good; even though I expected the punch, his right came so fast I couldn't block it. It was a hell of a wallop, sent me reeling-crashing against the wall, almost floored me. I knew then Nate felt the same way: All his resentment against me was in that crack on the chin.

My mouth was bleeding, my head ringing. Nate was so eager he goofed—he came at me. I got my arms around him, was too strong for him, not to mention the forty pounds of young muscle I had on him. I wrestled him to the floor, smothering his blows with my body. I sat on his gut, slugging him with both hands. I was so nuts I think I would have killed him if he hadn't gone limp and whispered, “Don't, Bucky. This... is... crazy stuff.”

“Call me Bucky Laspiza!” I gasped.

“Bucky L-Laspiza,” he said, turning his head away from me, the words coming out a tormented moan.

There was a bruise on his cheek; a trickle of blood ran out of one ear. I got off him and sat on the floor, feeling my numb chin. I was suddenly very sober and scared—I had damn near killed him. I stroked his thin hair and Nate began to cry. I kissed him on the forehead, muttered, “Oh, Dad, Dad! What's happening to us? You're right, this is crazy. Why can't you adopt me, give me your name?”

“Don't talk about that,” he said, hugging me with one hand, but still not looking at me. “I told you about the police... looking for me.”

“All this time? For what?”

“Murder. I... I... killed your father.”

I pulled away from him. “Stop snowing me, Nate. That's a lie.”

“No it isn't.” He was whispering again.

“I thought about it in camp—you're all I thought about. You've always told me how the oil company has such a careful check on their employees. All that security stuff. If you were wanted by the cops, they would have had you long ago.”

“They—the police—they... don't know I killed him.”

“Then there isn't any reason why you can't adopt me.”

He didn't answer. For several minutes neither of us spoke. Nate's eyes were shut and his face was so white I thought he had passed out. I stood up. Pulling Nate to his feet, I led him to a kitchen chair. For the first time Nate didn't look dapper, merely old. He leaned on the table, feeling of his face, staring at the blood that came off on his hands. I wet a dish towel with cold water and tossed it on the table. Nate held it to his face for a long while.

“Nate, that stuff about killing; it's a lie, isn't it?”

“Yeah. But I wanted to kill him. I used to dream how I had killed him—whoever he was. I'd dream of ways of slow... I suppose that's why Daisy never would tell me.”

“Dad, I'm sorry I hit you.”

He took the towel from his puffed face, looked at me. “I could cut off my hand for punching you, Bucky.”

“Nate, listen: I still want you to adopt me.”

“Son, in time you'll forget about it.”

“Can't you understand that I wouldn't want any other man for a father?”

“I've always been your father, Bucky.”

“Damn it, Nate, make it legal!”

He shook his head and groaned with pain. Then he said, “I just can't do it. Sometimes I wanted to but... Bucky, I've always been an also-ran—in everything I did. I never made the big leagues or had a good job. Well, a man can't be a complete blank. What I'm trying to say is that even a bad thing can still be the

“What are you talking about?”

“You see, if I had adopted you, or put my name down when you were born—it was that simple—why, in time

“What?”

“No matter if I was second best in everything else—in

“You mean you wanted to hold it over Daisy all her life. Is that it?”

“No. I loved Daisy. You should know that.”

“Bull! You did the 'right thing' and wanted to make damn sure she'd never forget it—you wanted to punish her! What did it do, keep you on that righteous kick all your life?”

“That's not so. Daisy is dead and I'm still young enough to—I can't even think of marrying again.”

“My God, Nate, I used to think of you as a man, but you're sick, crawling with self-pity!”

“What if I am?” he asked loudly, staring up at me. 'You're only a kid and can't understand what I've been trying to tell you. When a man has nothing else, even self-pity can be the most important thing in his life. It's been something I've clung to all these years. I can't give it up now.”

“But clinging to

“That's an unfair lie. We tried to have children. And I always treated Daisy well, better than any—”

“I know. You did the 'right thing,' and you're stuck with it—in your own crazy mind,” I said, picking up my garrison cap, straightening my jacket and shirt. Heading for the door, I called back, “Good-by, Nate. I wish to God I'd never come back, never seen you like this.”

“Bucky!” It was a wail that made me stop at the doorway.

Fumbling for words, Nate said, “Good-by, Son. I've been thinking of moving. I may be transferred to our L.A. office. I'll send you my address.”

“Don't bother.” I started down the stairs.

“Son! Wait.”

“I'm waiting.”

“Bucky if... if it means so much to you... After all, you're the only thing real I have left in life. Well, I'm willing to give you my name.”

“Thanks, Nate.”

“Tomorrow I'll see a lawyer and start—”

“Don't bother. When I said thanks I meant thanks for making it so it doesn't matter a damn to me now if I have your name or not. Good-by!” I rushed down the stairs.

I rang Elma's bell. When she came out I told her, “Let's get back to the hotel.”

She glanced over her shoulder. “I have to be careful, Bucky. You know my old man and Mama gave me hell about staying—”

“Tell her we're getting married in the morning.”

“Bucky! You kidding?”

“Aw, I have this G.I. insurance, can get an allotment. You've been good to me—why shouldn't you get it?”

Over a fat kiss, Elma said, “You don't know how good 111 be to you from now on! Let's go, lover.”

“Don't you want to tell your folks?”

Elma uttered her favorite word, then added, “We're engaged, aren't we? My old man would think we're lying and—I'll tell Ma later, when I show her the ring.”

3—

There was a knock on the end wall. Doc sat up, moving fast and quietly. The room was out of an old movie, with a false wall and a phony closet on the other side. Of course, I'd only seen the house once from the outside—when we came in, and I hardly had my mind on it—but from the street it looked like a narrow, rundown frame house. Yet on the inside, from the little I'd seen, it was very roomy, including this hidden room.

I was on my feet. Doc put the useless gun in his holster as the knock was repeated twice. He called out, “Yes?”

The entire wall—it was about eight feet wide—swung open silently and the old bag who owned this trap came in. She was a real creature, about as low as they come: a horribly overpainted face that looked like a wrinkled mask; her few stumpy teeth all bad; watery eyes; stringy bright blond hair atop a scrawny body and dirty house dress; torn stockings over veined, thin legs; and broken men's shoes acting as slippers. The very least she needed was a bath. The biddy's eyes said that at one time or another she had tried everything in the book—the wrong book.

She held an afternoon paper in her claw as she talked to Doc. She had ignored me from the second we'd come. In a rusty voice she asked, “Whatcha think, Doc, you're playing with farmers? Handing me this gas about being in a jam over some lousy investigation, ya got to hide out for a few days. A million bucks!”

She waved the newspaper like a red flag, her tiny eyes trying to X-ray the three suitcases.

I glanced at the paper. There it was, all over the front page:

SEEK TWO CITY DETECTIVES

IN MISSING $1,000,000 RANSOM

Of course I had expected it. It wasn't any secret. Yet actually seeing the headline, our pictures, was like stopping a right hook below the belt.

Doc yanked the paper from her hand, spread it out on his cot, and sat down. He even yawned as he started reading the story. I sat on the edge of my cot, my legs blocking the “door.” Without looking up from his reading, Doc said, “Okay, Molly, now you know. What about it?”

“Great Gordon Gin, you really got a million in them bags?” the old witch said, excitement making her voice shrill.

“We have clothing in those suitcases,” Doc said calmly, dropping the paper, facing her. “What's on your mind, honey?” Doc's sharp face was relaxed but his eyes were bright.

“You know what's on my mind! This makes a difference. They'll be combing the city tight! I'm taking a hell of a risk in—”

“How much, Molly?” Doc cut in.

“This changes our deal!”

“How much do you think it changes it?”

I could almost see her pin-head making like an adding machine.

“It'll cost you a thousand bucks a day!”

Doc shrugged. “I'm hardly in a position to argue, my dear. Okay.”

A grand a day—each!” this walking fright rasped. Doc grinned. “All right, but don't push it too far, Molly. Two grand a day it is. And at least give us some decent food—my stomach is tired of your canned slop.”

“Food shouldn't worry you.”

“Oh, but it does. I pride myself on being a gourmet.”

“Skip the big words. I want my money now, and two grand every morning—in front. I ought to ask you for back rent at the same rate but I'll give you a break.”

“Thank you, my sweet. Your kindness is blinding.”

“None of your smart lip, Doc. Give me my two grand for today.”

“Of course.” Doc picked up his coat, which was crumpled over his pillow. Pulling out some bills, he counted them swiftly. “I only have twelve hundred here. I—”

“No funny stuff, Doc. I want all my money. Open them bags!”

“You wish to be paid off in clothing? Stop screaming; you'll get the money.” Doc looked at me. “Give me some cash, Bucky.”

As he walked over to me I knew what was going to happen, what

My coat and holster were hanging on the back of the one chair. Doc did it neatly—grabbing my pillow with his left hand, yanking my gun out with his right. It was practically all one motion, his back toward Molly. He spun around and shot the old biddy twice in the body. She fell face down, as if her legs had been yanked from under her, the muffled shots echoing in the room like tiny thunder. The acrid stink of gunpowder filled the place, a welcome odor compared to the usual stale smell. And my pillow needed ventilating.

Without a sound, Molly turned on her side, curling up like a burning worm, hands pressed to her scrawny belly. Her mouth was wide open and her plates came loose, pushed half across her lips. Her eyes were staring down at her stomach too, as if she had forgotten all about us, was so busy dying she was in a world of her own. After a few seconds the look in her eyes was too steady and I knew she was dead.

Handing me my gun, Doc listened carefully for a few seconds, one slim hand up for silence. Then he asked softly, “You knew it would come to this, Bucky?”

“Yeah.” I holstered the rod. I didn't feel a thing at seeing the witch die. It had been so different when Betty was killed. That had ripped me wide open. I pointed to the corpse with my shoe. “What do we do with that?”

Doc knelt and took her pulse. When he let the thin, pale hand fall it made a sharp sound against the floor. Doc stepped through the “door” and returned a second later, dropping a worn rug on the floor. “Wrap this around her before she bleeds all over our room. We'll park her in an upstairs closet, let the rats decide if she's worth eating.”

“Do you think she told anybody?” I asked, kicking the rug over Molly, wrapping her in it as if she was a hunk of baloney.

“Not this pig. She probably figured on going for the dough alone by killing us in our sleep.”

“Suppose somebody comes around asking for her?”

“Molly was never the friendly type. If the doorbell rings, we'll face it then. Another few days and we'll be ready to blow this hole.”

“And go where?”

“I haven't the faintest idea—yet.” Doc smiled down at me as if talking to a kid asking dumb questions. Sometimes that annoyed the devil out of me.

We carried the rug and Molly upstairs. I'd never seen much of the house before and it was awful creepy, full of broken furniture, thick dust and dirt over everything. In Molly's bedroom we found stacks of old newspapers, boxes of dirty clothes—things piled high as the cracked ceiling. It was strictly nutty, miser stuff. And if our room was under this—old as the dump was—it was a wonder the floor didn't collapse. Her closet held torn dresses, hills of worn shoes, scattered dirty underwear that had to have come from a trash can. Molly never even threw a used toothpick away. But her bed was a modern foam mattress on smart iron legs, and in a cedar bag we found a mink coat smelling clean and new—a good mink like Judy wanted.

Doc laughed at the coat. “Bucky, as you see, vanity never ages. Why, this must have set Molly back at least a thousand, even if she bought it hot. If we look hard enough we'll find money here.”

“Let's get back downstairs. Makes me nervous leaving the bags.”

“I wasn't thinking of her lousy few bucks,” Doc said, almost to himself. “If we ransacked the house, make it robbery, the work of a punk who had his eye on miser Molly, killed her while hunting for the loot...”

“That's an idea,” I said, admiring Doc. His brain was always ticking.

“No.” Doc shook his head. “Be a waste of time. Ballistics will check the lead in Molly and link it with the slug in the kidnapper; they'll know it's us. No, forget it. Shut that closet door tightly and stuff the cracks with paper—the old gal will smell rather strong in a few days.”

“I hope we'll be long gone from here in a few days,” I said as Doc went into the hole she called a bathroom, began poking around. I took some newspapers—dated two years ago—and closed the closet door as hard as I could, got down on my knees and began stuffing paper around the door. That was another thing about Doc that sometimes got on my nerves—his habit of ordering me about. Of course he was the senior man, but this was hardly police work!

As I was stuffing the top of the door, Doc returned, holding a small bottle.

I asked, “What is it—dope?”

“It's a blond rinse. She has a case of the junk. A lot of cosmetics.” He pocketed the bottle. “Move some of those boxes of junk against the closet door—no, put a couple piles of papers against the door. We'll look through the boxes—we ought to find some men's clothing. And keep away from the windows.”

“Hell, the windows are so grimy nobody could see us.” I moved a big stack of old papers against the closet door, began to sweat. Then I kicked a cardboard carton open. “What do we need clothing for?”

It was real disgusting, the lousy boxes were just that—full of all kinds of bugs, even worms, and a startled mouse. Doc picked out a dirty, cracked leather windbreaker and a couple pairs of shabby pants. I still didn't know what he wanted with this junk. Shaking the windbreaker, Doc grinned at me, said, “I wonder what thug owned this? Must be a dozen years old.”

“When do you figure this joint was last used as a hide-out, Doc?”

“Hard to say—perhaps ten minutes before we pulled in. Who knows? Back during Prohibition this was a blind pig and a popular hiding place for the big shots. Molly even had girls stashed away for the boys. The last I know of anybody using this was Baldy Harper, who was wanted for a knife party back in 1949—or was it 1951? I wasn't on the case but—”

“The hell with it. Let's get back to the suitcases.”

“Sure.” He slapped me on the back, hard. “Don't get your nerves up, kid. It's only paper.”

“But a million bucks is so

We looked through the kitchen, scattering roach patrols. The bugs must have been a frantic lot, for the cheap bag didn't have any food around—a few cans of beans, stale coffee, a can of milk that smelled awful. The odd part was, she had a spotless refrigerator, and completely empty. Not even a brew. Sitting on an unstained part of the kitchen table, I asked, “Now what, mastermind?”

Like Nate, Doc never got rattled. He laughed at me. “It's simple, S.O.P.: We keep sitting tight.”

“The only think tight will be our guts—we have to eat.” And Bucky boy, you well know how much I enjoy eating. We shall eat very well, too.”

“How? Even the roaches are having it rough.” I glanced at my watch, the same one Nate had given me for graduation years ago. The boxer's arms said it was ten to six. “It's damn near suppertime now. You going to saute the bugs, or maybe roast those old clothes?”

“I wish you'd put that childish watch away. Time has little meaning for us now. A timeless world is one of man's goals. We are fortunate to—”

“Okay, Doc, but we can't eat words. Exactly how are we going to eat so 'well'?”

He patted the clothes he had tossed on a chair. “I may be fairly well known in this end of town; I used to have a post here when I was a harness bull. That's how I knew about Molly and this hide-out. While that was over sixteen years ago, it would still be far too risky for me to venture outside. But you can go out and buy—”

“Me?” I jumped off the table. “You're talking like a man with a paper head! Remember the whole damn force is looking for the

Doc nodded, that wise tight smile on his unshaven puss, as though I'd just made a funny. “I know. The beat cop most certainly has a general description of you: young, stocky, black hair, well-dressed.” He pulled out the bottle of hair dye, threw it on top of the old clothes. “Disguise has become a lost art among you younger detectives. Look, as soon as it's dark a blond, middle-aged man in worn work clothes with a blanket around his middle to make him look stout will easily be able to walk the two or three blocks it will take you to find a delicatessen. The nearest one is run by an old German, a very clean store. You'll be perfectly safe. You won't buy much: beer, a few packs of butts, sandwiches. Ordinary staples. Granted it's a chance, but a very little one. It's comparatively simple to make a young fellow look old, but to make a man my age look young—well, it would be much more of a chance if I tried it.”

“I'd have to be crazy to buy that!”

“Bucky, Bucky, you sound as if I was throwing you to the lions. We're in this together all the way. Do you think I'd let you take a real risk? Hell, if you got caught they'd beat this hiding place out of you in no time, and I'd be collared too.”

“But Doc, going out... seems such a dumb thing.”

“Okay. We can use up these beans tonight, but tomorrow we'll have to eat. There's little point in our being the richest men who ever starved to death. I told you before, Bucky, we have to meet things as they come up. Now we have to cross the food bridge, just as a half hour ago we had to take care of Molly. Look, I know my business. I'll fix you up so you wouldn't recognize yourself in a mirror.”

“Well... I guess there's no sense in us arguing. We do have to eat, but... Doc, what are we hanging around this house for, giving them a chance to close in on us?”

“This is the smartest move we ever made, our salvation. Kid, you've never been through a dragnet; you don't know what it's like. The tightest man hunt in police history surrounds this city right this minute. Not only our police force, but the F.B.I. and the state troopers have undoubtedly thrown in hundreds of extra men—every guy anxious to make the big collar. Two men carrying bags couldn't reach the highway, or even get within shouting distance of the railway station or bus terminal. We have to wait a few more days, maybe a week or two, to give them time to relax the dragnet, make everybody feel positive we've left town. Time is on our side, not theirs. Suppose we have to wait a month, even a year. The pay is right and—”

“A month!” I exploded. “I'll go stir nuts. Not even a radio in the house.”

“Take it easy, Bucky boy, learn to relax. You must have heard of the St. Valentine's Day massacre in Chicago—way back?”

“What's that to do with us?”

Doc sat on a kitchen chair, stretched his legs. “The real head of the mob, the joker they were after, was in that garage but they didn't kill him. Matter of fact, he died several years ago—in bed. But the killers had seen him go into the garage and they kept an around-the-clock watch on the garage building for over six months, after the massacre. This mob leader was smart, he stayed in that garage, in hiding, for

“You mean we might have to spend that much time here?”

“Maybe. Or somebody like a building inspector might come around ten minutes from now and we'll have to make new plans.” Doc felt in his pockets, then held out his hand. “Give me a butt—and some fire. Suppose we do stick here for a half a year—isn't a million bucks worth it? What's a few months, a year, out of our lives? It's simple if you learn how to unwind. That's the secret of a long life.”

“Come on, Doc, you can talk plainer than that,” I said, giving him my last cigarette and a match.

Winking at me over a cloud of smoke, he said, “I keep telling you to remember the one big advantage we have in this setup—

“So what's the big fat difference?” I asked, watching my last butt working in the middle of his dirty face.

“When you've done police work as long as I have, you'll—”

“We're not exactly the police in this case.”

Doc showed me his neat teeth—and they looked dirty, too. And he was the character who always carried a little can of tooth powder, insisted on rubbing his teeth clean after eating. He said, “That's not as much of a wisecrack as you seem to think, Bucky. When you spin a coin, both sides are affected. Now stop shooting off your big mouth for a moment and listen. It's on the planning level that most capers strike a reef. Punks make a lot of plans beforehand, with no way of knowing what the actual realities of the situation will be. They plan a deal to go a certain way; if it goes another, they're sunk. In the pattern of crime, plans equals mistakes. Also, plans can become known, and the more you plan the more errors you overlook. What I'm telling you is this: Without making plan one we stumbled over a million dollars. Any errors we make will come from facing the problems as they arise. I believe that with any sort of break we'll get out of this dump, then out of the country, to enjoy the money.”

“But how, Doc, how?”

He blew smoke at a roach crossing the table. “Don't be so impatient. I don't know—I just told you we haven't any set plans.”

“Damn it, we have to plan our next step!”

“Why? Sometimes it's best to stand still, not take a step. Give me time, Bucky—I'll think of an out. I always have. Here, since you're so in love with plans, here's a few precautions. We'll keep to our hidden room most of the time—less chance of anybody spotting us from the windows. Somebody rings the doorbell, we don't answer. Every night, for a half hour or so, we'll leave the kitchen light on, and the light up in her bedroom.” Doc crushed his cigarette on the table, wasting half of the butt. He stood up and yawned. “For the present our immediate steps are simple—get some sack time and stop worrying.”

As we started for our room, he told me, “Shut your eyes, Bucky. You want to be doing something, then start memorizing where the furniture is. Never know when we might have to move in the dark.”

I followed him to our room, keeping my eyes open. He closed the secret “door,” then snapped on the light. We stretched out on our cots. I picked up the paper while Doc went to sleep. But I couldn't read—the pictures of us already looked like mug shots. I dropped the paper on the floor. There were a few spots of Molly's blood. Despite stomach wounds she really hadn't bled much. Would she have tried to kill us, take the dough, like Doc said? Seemed to me she would have gone for a possible reward, blown the whistle on us.

I got up and opened the “door.” There was a tiny John next to the kitchen. If this was such a hot hide-out, why didn't they think to build a toilet in the room? I washed up—there never had been any hot water—dampened some toilet paper then soaped it up, returned to our room. I was down on my knees trying to get rid of the bloodstains when I heard Doc chuckling. He said, “When the F.B.I. shot Dillinger down in front of a theater, they say people were sopping up his blood with handkerchiefs and newspaper for souvenirs.”

I didn't bother answering. Sometimes Doc's pearls of wisdom gave me a stiff pain. I couldn't get much of the blood off and when I went back to the bathroom I tried walking in the dim light with my eyes shut. I banged my knee.

Doc was sleeping again when I closed the “door,” snapped on the light. I sat on my cot, far too tense to sleep. I didn't like the idea of going out; it frightened me silly. But Doc was right, we had to eat—right now I wanted a drag, wanted it badly—and it had to be me. I didn't want to think about going out, tried to think of

I stared at Doc's skinny back, envious of the way he could pound his ear. He wasn't asleep. He must have felt my eyes on him; he suddenly rolled over, told me, “Maybe that kid's watch of yours will come in handy after all. Wake me when it's eight o'clock. You have to leave before the stores close. I could go for a shrimp salad sandwich—on good German rye.”

Then he turned over again and really went to sleep.

I cursed him, to myself, for no reason. Stretching out on the cot, I glanced at the fighter on the watch face. The paint on his left shoe was peeling. It wasn't even seven o'clock. Crazy, how the watch upset Doc, or maybe amused him. Like Elma, he was always after me to buy a new one—had tried to give me an expensive, self-winding job.

I never told him why I had to keep wearing it. I guess I couldn't have put it in words. But I wanted to wear it. Judy never noticed it and Betty thought it was cute. Elma was mad because I... What was Elma doing now? How was she taking all this? Probably wishing she could get her mitts on me—and the money.

Elma knew about Nate giving me the watch, but she kept nagging me to throw it away. But then nagging was her way of life. Elma the lump. Would it have worked out okay if she hadn't had her insides taken out—that lousy operation?

Or was our marriage all wrong from the jump?

4—

My marriage to Elma worked out fine, at first. I did a lot of thinking about Elma while I was in Korea. She used to write me regularly, dull letters but the

It wasn't much of a worry because for a time I didn't think I was coming back. I guess I wanted to die; you know, kid stuff—felt it would spite Nate. But dead or alive, I wanted to be a big hero. Again, it might have been to prove to Nate I could make it on my own, didn't need him. I still felt nameless, and I suppose I thought if I became a hero, even a dead one, at least I'd be a

Okay, it sounds childish now, but then I considered myself the toughest thing out, and I guess I was. I was anxious to fight anybody or anything. I kept going up to sergeant and being busted back to private over some brawl. The weird part was that although I saw more than my share of combat and shooting, kept volunteering for patrols—and once I was the only guy who came back—in actual combat I never got a scratch. They gave me two Purple Hearts but both of them were phony.

There was an Italian hick from Maine I got to be kind of pals with. Perhaps because I'd considered myself an Italian for so long I couldn't stop. Most of my fist fights were over some slob making a crack about Carmen Brindise's name. Carmen was a little guy who spoke with a nasal twang, smart and tough. He knew all there was to know about hunting and fishing. In his wallet he carried fish hooks and a line and any time we were around a river, the ocean, even the damn rice paddies, he had a line over. Not that I ever saw him catch anything, either.

One night when we were resting between patrols, and supposedly in a rear area, we were sharing a pup tent. It was that cold winter when it seemed I'd never get real warm again. Carmen had made some rice wine and we were tanked up on the junk. Matter of fact, it was so freezing cold, the bottle broke and I got a nasty cut on my arm taking glass out of the rice mash. Carmen was telling me about how he used to go hunting up in Maine and Canada and on cold nights he'd stick a finger out of the tent and say, “Feels two dogs cold,” and take two hunting hounds in with him for warmth.

In the middle of the night we were high with wine and Carmen was doing his act, sticking a gloved finger out and announcing it was now “ten dogs cold.” Not that we had any dogs, you understand. The last time he did this, a rifle slug blew the top of his head off, splattering me with blood. When the medics reached us they put my bottle cut down as a wound and I got my first Purple Heart.

The second time, I was hitching a ride in a supply truck when a plane came in strafing, killing the driver. I got a bad cut on the head diving out the cab for the ground. When I came to in a base hospital I had another Purple Heart. I suppose that second one was legit.

I didn't pay much attention to the medals, but they helped me get home on rotation and by then the war was over. I figured I'd tell Elma it had been a quickie marriage, let her get a divorce. But Elma surprised me.

She had put away over a grand from my allotment checks and had been making good money working in an aircraft factory. So when I came home I found we had our own apartment, a three-room deal in a swank elevator house. The truth is, for the first couple of months I was nuts about Elma. There was a big sex business with us. She wasn't any beauty but was wonderfully curious about so many things, and we made up for the years I'd been away. It was terrific. I mean, we'd have these workouts and then in the morning she'd take off for work while I'd sleep until the middle of the afternoon, then lounge round the house, watch TV. Even the apartment was kicks then—compared to the tenement I'd known—and I'd often put in hours cleaning it up, waxing the floors, waiting for Elma to come home and make supper.

Her aircraft job folded a few months later; all the women were laid off, and Elma found an office job at half her former salary. I didn't know exactly what I wanted to do. I took a lot of civil service exams, my being a vet giving me extra points. In the meantime we needed dough and I went from one job to another, none of them really much. I was a restless sour ball, always socking the boss or a customer. Like I became a stock clerk in a big clothing house. Might have been a good deal; some of the clerks went on to become salesmen and store managers. My boss let everybody know he'd been a Marine and when I happened to mention I had a double Purple Heart, I was his boy. He put me on the floor, selling. The third day I was a salesman some crumb tried on a loud, checkered sport coat—something he'd picked out himself. When he looked in the mirror and said, “I look like a wop in this,” I flattened him before I realized I was swinging. He sued the company and that was very much that.

I worked in a supermarket; turned out I was good at displaying and selling vegetables. Only for some dumb reason I told them my name was Bucklin Laspiza, got screwed up on my Social Security and had to leave the job after a few months—when I was starting to know what it was all about.

Another time I became a truck helper. If I became a driver and got a union card, the pay would be high. But the fat-jawed dispatcher thought calling me “Fountain Penn” was such a witty remark that I had to break his nose after a few weeks.

Considering the way she acted later on, it was odd Elma never complained about my job turnover then. It was really her sickness that changed her, I guess. One of the reasons we got along so smooth then was, no matter how often I got the sack, she didn't nag about it. It was about this time she began to get tired easily and at first we thought she was pregnant. I think I wanted a kid; at least I kept telling myself he wouldn't have to worry about his name.

The doctor said Elma had a tumor, a big one, and needed an immediate operation. She had a hysterotony, or whatever they call it, where they cleaned her out. The doctor explained that he had left her sex roots in—and maybe I'm not using the correct terms—but actually I think he was wrong. It was a difficult operation and for a time they didn't think she was going to make it. It took every dime we had. Her folks didn't have a penny, and I doubt if they would have helped us anyway—they didn't look with favor upon taking a “bastard” into the family. I wired Nate, care of his local office, for three hundred dollars and got it within a week.

For a time it was even sort of tender fun nursing Elma back to health, but after that she was never the same. For one thing, she completely let herself go, became all soft and baggy, a regular heavyweight of lard. And she suddenly decided she couldn't work any more—hell, it took months before she would even get out of bed.

Things have a way of working—sometimes—and we were both happy when I was appointed a police officer, sent to the police academy for three months. I was nuts about the job. It did something to my—I suppose “ego” is the right word—to be sporting a badge and a gun. Maybe it was silly, but I was very pleased with myself, full of a deep feeling of satisfaction. You see, I was no longer a nameless nobody. I was now

I got along okay in the academy, worked hard at it. Although I was still walking around with a ton of chips on my shoulder. If I wasn't one of the top ten students, I was a long way from the bottom ten, too. Here's something else. Around our block we always made a point of chasing any colored kids that happened to come by. Don't get me wrong, we weren't any lynch mob—we chased all kinds of kids—but a colored one was a sure target. So the only guy in the whole class I really got to be a buddy with was a dark brown fellow named Ollie Jackson. I suppose you'd call him “colored”; actually his face looked like the United Nations. His folks had come from the Hawaiian Islands and along with his mahogany-brown skin he had Oriental almond-shaped eyes, and an Indian's hooked nose. Ollie was one of these calm, easygoing types, and strong as a barrel of dead fish. At first look you'd take him for a short, fat joker. That was a mistake because he wasn't so short and he wasn't fat—it was all muscle, hard as steel. We got to be friends in the boxing class.

Most of the fellows took it easy, even with the heavy gloves on. But with my ring experience I had it all over the rest of them and I used to work over anybody I got into the ring with. Sure, I was going for mean then. I tangled with Ollie one day and had no trouble clouting him. He was so wild I could really tee off, but I couldn't floor him. He kept rushing me and finally managed to clinch, put those thick arms around me in a bear hug—and squeezed. When the ref parted us my arms were numb from the elbows down—I simply couldn't raise them. Ollie grunted with pleasure as he started pasting me with roundhouse swings, each feeling like a baseball bat across my face. I wanted to go down and end it, but I had to admire this cat: He'd taken everything I'd dished out, waiting for his chance.

I was so groggy I really didn't remember a thing until I woke up in the middle of the night, beside Elma. I had a headache for days. But the next morning when Ollie came over to ask how I felt, I said great and we were ace buddies—because I knew damn well his head was hurting him, too.

When we graduated, we were assigned to the same precinct house. It was a rough section of town and Ollie the first “colored” cop on duty there. He got hell the first few days—until I started hanging around his post on my off time and between us we walloped respect into a lot of would-be tough studs. Ollie was always calling me down for clouting first and asking questions later. The truth is, I was belting a lot of characters and there were plenty of complaints coming in about me. I didn't know this until the sergeant in charge of our platoon took me aside and told me, “Penn, you're new to the force and this is a deprived area, and tough. You'll come across provocations every tour of duty—but that's part of your job. You've got to stop being on edge all the time. I've been a police officer for a lot of years, so believe me when I tell you a tough cop always ends up a dead cop. You're making a name for yourself, but it's a lousy name. You look like an intelligent kid, so stop taking the easy out.”

“What easy out, sir?” I asked, the “name” bit making me tense.

“Use your head more and your fists less. I'm talking to you because I think you have the makings of a good cop. Only you got to relax, use your judgment more. Don't become a hoodlum with a badge.”

Of course, the troubles I was having on the job were nothing compared to what Elma was giving me. It seemed she had nothing to do but slop around the house and complain. I tried to be fair about it, remembering how she had catered to me when I got out of the Army. But Elma never wanted to get better. She let herself go to a shapeless ton, and whatever the sex thing was between us, it vanished. Actually I think the operation took all desire out of her. She got so big she was a freak—there simply wasn't room for the both of us in one bed. I began sleeping on the living-room couch, which wasn't any dream either. I was nice about it, explaining my changing tours would keep her awake. But not getting a decent night's sleep made me sour on the world most of the time.

The biggest trouble was money. I couldn't blame her for beefing. During my rookie probationary period, in fact up till the end of my first two years, I was making under $4000 a year, with my actual take-home pay a few dimes and quarters over sixty bucks a week. And that didn't make it. Not that we were living big, but the rent was $92 alone, with no possible cheaper apartments to be found. When Elma had been working the aircraft, she was pulling down $110 or $125 with overtime, so the rent hadn't made much of a dent. Or when we were both working, it hadn't been such a big item. But on my peanut salary, two weeks' pay about covered the rent and gas and electric, the phone bill. By stretching each penny we just about made it. Elma was always nagging that we needed a hi-fi, or a toaster, or about having to wait two weeks to have the TV repaired. Or she

When I told her to shut up, that the watch was still working fine, she repeated her favorite four-letter word half a dozen times—as if proving something.

Whatever we needed for the house had to be bought on time, so we were always in debt, really strapped. Elma's beef about money was legit, but what sent me straight up was this dumb idea she had that there was all sorts of graft for a beat cop to put his hands on. She would nag that I was a dummy who wasn't trying. I'd keep telling her the old days of a patrolman even taking apples on the cuff were gone. I didn't doubt but that there was cushion money around, but only for the brass. Like I knew damn well there was a book working in the rear of a meat store on my post. I also knew—also damn well—it couldn't operate without the knowledge of the precinct captain and downtown. This joint had been taking bets for

It was so petty it made me feel lousy. Ollie told me, “Why bother with that stuff? You get a few bucks' worth of meat for free—big deal.”

But Ollie could talk; his wife was a schoolteacher. When they bought a new car and I made the mistake of mentioning it to Elma, she blew her stack. “And we haven't even got decent furniture, a rug, a vacuum cleaner, much less a car! I'm ashamed to ask my folks up here.”

“If they ever should decide to come, tell 'em to take a bath first. Honey, Ollie makes it because his wife has this good job. Why don't you try for some part-time work? Not for the dough so much, but it would be good for you.”

After sputtering her favorite word, she said, “You know I'm not strong, that I nearly died. What you trying to do, get rid of me?”

“Stop it. The operation was almost a year ago. If you got out of the house more, you wouldn't be so sickly.”

You see, I tried as best I could. For a time I had a job as a bouncer in a small cafe, but that only lasted a few weeks. My change of tours killed it, and then the sergeant called me in for another session, warning me it was against some civil service law for a cop to have an outside job.

Elma seemed to think I was holding out, rolling in dough. She began sopping up a lot of beer during the afternoons—or as much as we could afford—and reading these fact-crime magazines. When I'd come home Elma would give me a beer-breath full of, “I was reading about this cop who they found had a ten-thousand-dollar boat, a Caddy, and owned a small apartment house. And he was a hick cop, making less than three grand a year.”

“What jail is he in now?”

“Don't you be so damn smart with me, Bucky. Smarten up on the job if you got to be a wise guy. Yeah, he was caught, but think of all the cops with their hands out who

“Aw Elma, stop clawing at me. If there was any graft around I'd get it but—”

“But all you get is a few pounds of leftover meat now and then.”

“Lay off me. I'm trying to get something going for myself. My best bet is to make a good collar, be made a detective third grade. It would mean an immediate raise of a few hundred dollars, then almost a thousand more a year soon. And in plain clothes, a guy could find a lot of gravy. Look, instead of beefing all the time, at least clean up the house. It's a pigpen.”

“That's me, Mrs. Pig Penn,” she said, well knowing any cracks about my name made me get up steam.

I slapped her moon face. She broke into tears and I said, “I'm fed up with all your self-pity. You remind me of my old man and his—”

“Nate wasn't your old man.”

I backhanded her and she fell to the floor. I stared down at her, remembering how she had stood by me in my trouble with Nate, the rest of the block. And I hate hitting women. I pulled her up—which was hard work—held her as I said, “Okay, Hon, I'm sorry. You think I like scrimping? I'm trying my best to get my hands on more dough. But you have to try too. Stop bloating yourself with beer. Watch your diet, get out of the house every day. You're still young, no sense in looking... so big.”

“You don't even love me any more,” Elma whined.

“Sure I do. It's merely my change of tours, and you being so sickly that... Come on, let's go to bed.”

But her soft bulk, along with the knowledge that she didn't get the slightest kick out of it any more, made it impossible for me to have relations with her, and she began sneering at me for that, too. I didn't worry. I never was much of a lover-boy; sex was rarely on my mind. I started staying out of the house as much as possible. After my tour of duty I would take a few drinks and roam the streets. It wasn't just keeping out of Elma's way; I liked being a cop, hunting crooks. I told myself that by walking around I might luck up on a good collar, make detective. It wasn't only for Elma; I wanted to be able to buy a tie or pack of butts without a debate with myself as to whether I could afford it.

I'd often read in the papers about some off-duty cop coming on a stick-up, or something. When I was on the four-to-midnight shift I loved roaming the dark streets in the early morning hours, looking for trouble. I found it once—a squad car in a downtown precinct stopped me early one morning, thinking I was a suspicious character.

Another time I collared a drunk stealing a car. I got a pat on the back from the desk lieutenant and a sarcastic request to keep to my own precinct. I really tried, even paid out eating money to bone up on the sergeant's exam at some school. But I didn't pass high enough to make it count.

Things work out funny. The thing I thought would make me a dick was a silly deal that happened on my own beat. I was on an eight-to-four tour and at 3:15 p.m. there's a loony kid perched on the roof of a tenement. He was a skinny, nervous boy of about eighteen, upset because the Army had rejected him, of all dumb things. I went up to the roof and there's his bawling mother and a couple other old women. We couldn't get close—he threatened to jump. I had to race down six flights of stairs to put in a call for the emergency squad and then back up to the roof again. Somebody had called a priest and he was up there, trying to talk the kid out of it.

I had a deal cooking for 4:30 p.m. Some babe was having trouble with her boy friend and wanted to move her things out of his room without getting her head handed to her. She had a trunk and a TV to move, so she had set up a date with a moving van. When I told her I'd be off duty then, she said it would be worth a five spot for me to be around, in case her guy talked out of turn with his mitts. The emergency squad sergeant had a net below and there was several of his men around, but when I told him I was due to go off at four, he said for me to stick around.

It's getting near 4 p.m. and now they got a rabbi and the priest talking to this dumb kid, and he still wanted to jump. The two ministers were putting their heads together for a conference and I was mad as hell. If I didn't show, all the babe had to do was call the beat cop and I'd be out my five bucks. All because of a nutty jerk.

At five to four I walked across the roof toward him, and he wailed, “I'll jump if you come a step nearer!”

I said, in a loud whisper, “Go ahead and jump, you dumb sonofabitch! Go on, get it over with!”

The ministers heard me and while they were giving me the big eyes, damn if this jerk doesn't leave the edge of the roof, walk toward me. I tackled him and that was that.

I made the moving job but figured the ministers would have me up the creek. So that night I find myself on the front pages, being praised for having used the “correct psychology”! It wasn't a big story, but my name was there and it was in the radio and TV news. Even my platoon sergeant gave me a snow job the next day and I figured this was it, I'd be made a detective. But nothing came of it. The kid's folks gave me a big speech of thanks, but that was all.

Nothing worked for me.

One morning a few months later as the platoon lined up a few minutes before eight, we were given parking tickets, told that alternate side of the street parking, to help in cleaning the streets, was now in effect, and to start giving out tickets to any car parked on the wrong side. I told myself this should be good for some cushion, but as it turned out, most times the guy who owned the car wasn't around. Now and then I got a few bucks for not writing out a ticket, but it was too open and risky.

The storekeepers, who usually parked their cars in front of their shops, were kicking like the devil about this alternate deal. I kept working on them, got to know most of their cars. I would go in and warn them to move their heaps. Most times all I got was a fast “Thanks,” or a promise that they would remember me at Christmas.

It got so I hardly bothered handing out tickets, but in the end it paid off—unexpectedly. I met Shep Harris.

The no-parking limit was from 8 a.m. to 11 a.m. Harris was an optometrist who had just opened an office over a shoe store. One morning at about a quarter to eleven I saw this smart red MG parked on the wrong side of the street. It wasn't a new car, but still I figured anybody with a foreign heap might be glad to pay a few bucks to avoid a ticket. When I asked the clerk in the shoe store if he knew who owned the car, he told me, “That's Harris's car, the guy that moved in upstairs. Usually he doesn't get here before noon. Some job, hey? Bet it does a hundred with ease. Now me, I say if you have a car, what good is a two-seater? I'd want to take the family...”

I walked up to his offices. A bell rang as soon as I opened the door, and the office was nicely furnished, everything new—meaning ready money. A runt wearing a white silk jacket, thick glasses making him look owlish and nervous, his narrow shoulders all bones, came in from the other room. He gave me a selling smile as he said, “What can I do for you, officer? Need glasses?”

I took him for a little older than myself, maybe twenty-seven, twenty-eight. “That your MG downstairs?”

“Oh Lord, did somebody crash into it?” he asked, racing for the window. Then he turned, asked me, “What's wrong with it?”

“This is Wednesday, no parking on this side of the street until eleven.”

He glanced at his watch. “Perhaps you do need glasses.” He held up his wrist so I could see it was exactly eleven.

“Okay, mister. I went out of my way to be nice to you. The next time I'll slap a ticket on the car, talk to you later.” I started for the door, angry.

“Now, officer, I was merely joking. I have too many tickets against my record now. I appreciate what you've done. Do you drink?”

“Not on duty.”

“Of course. Here.” He handed me five bucks. “As a personal favor to me, buy yourself a pint on your way home. A little token of my appreciation. Drop by any time.”