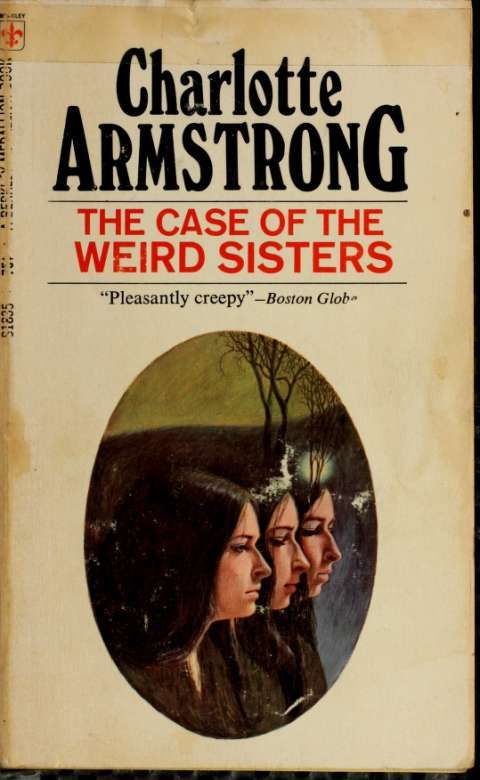

"The Case of the Weird Sisters" - читать интересную книгу автора (Armstrong Charlotte, Archive Internet)

|

PROLOGUE

The train that pulled into Ogaunee, Michigan, at 9:15 Friday morning was in no hurry. It settled to a stop and let go with deep metallic sighs, as if it would undo its iron stays and rest awhile.

A tall man in a gray overcoat swung aboard, went down the plushy day coach to a seat along about the middle, laid his coat in the rack, and sat down, settling back with such sudden ease that he seemed to have been there for some time, with the lazy dust rising and falling around him in parallel bands of spring simshine.

A sticky face rose over the seat top ahead Unblinking eyes looked at htm with the insulting stare of a child. The tall man met the infant's eye rudely. In a moment the child's head fell toward its mother's ear and the tongue came out coyly to wrap itself around the edge of a lolly pop in an ecstasy of embarrassment. MacDougal Duff relented and gave die baby the regulation adult smile. Only the youngest and most unspoiled could keep that look for long when met in kind. This one's clouds of glory were shredding thin already. And mine, thought DuflE ruefully, are strictly synthetic.

He was bound for Pinebend, a few hours away, where there was an Oneida reservation. Duff was interested in Indians, this trip. He had been rambling through northern Wisconsin and in and out of the Upper Peninsula, collecting impressions for Duff's History of America, a most unorthodox work which woxild take him, he cheerfully hoped, the rest of his life to write, between murder cases. Ogaunee was a central place to stay.

The train woke with a jerk. Movement on the platform caught his eye. On the dreary boards between him and the shabby littie wooden depot with its gingerbread eaves stood a girl in a gray flannel suit with a green scarf at her throat and no hat on her dark hair. She seemed to be screaming his name.

Did he hear it or read her lips?

"Professor Duff! Oh, Professor Duff! Please! Mr. Duff!"

For a moment his stare was blank with surprise. Then he smiled and lifted his hand.

Whatever the girl was after, it was more than a friendly wave. Her face kept its trouble. She continued to implore him as the train began to move. She even ran along a few steps as if her urgency couldn't let it go. Then she gave up and stood still, and the train chugged around a sweep of track and wiped out Duffs view of her.

Queer.

She had been in one of his classes. So many had. History 2b. Some time ago. Front row. Therefore beginning with A, B, or C. Probably not A. Too far from the right. Nice ankles, he remembered. Hence the front row or he couldn't have remembered the ankles. Miss B., then. Or C. An intelligent face. He'd enjoyed lecturing to it. Responsive. Sense of humor. Irish in her, he'd thought. Not pretty, not quite, but with a flare of spirit that was just as good. Dark hair, blue eyes. Brody? Small chin, wide mouth. Brogan? Brannigan? Skin tight over the cheekbones. A neat foot. Neat round slim body.

Cassidy, was it? Corcoran?

Ah, well, when he remembered her name he would telephone back from Pinebend. Ask Susan. Perhaps the girl was broke and stranded. If so, Susan would take her in.

The train humped itself across a swamp. Inside, dust motes shifted in the dry air. Duff gave his ticket to be punched. The conductor put the pasteboard in Duffs hatband and gave the child a playful swipe with his hand. Duff looked out the window and played his game with the scenery. When those black stumps had been trees, the ground beneath sunless and spongy, a trail would have wound just there, through that Uttle notch, skirted that water, been wary of that marshy margin. Wild birds would have come down there, and the wild man hidden in those reeds. . . . The girl's name was Brennan.

Maybe she knew that MacDougal Duff had retired from teaching and had become, for his bread, a solver of murder cases.

Murder? Duff looked out at the little hills.

The girl in a gray suit and a green felt hat came out on one of the stone stoops and closed the door gendy behind her. She looked at her watch nervously. Caught without its humanity, at two minutes of six, Thursday morning, the South Side Chicago street looked clean and bare in the thin light of dawn.

At six, exactly, a big gray sedan nosed around the corner and came softly along. It was the last word in beautiful American cars. The last for a long time, thought the girl as she walked down the steps with her suitcase.

Tlie chaufeur said, "Good morning. Miss Brennan. You're pretty prompt."

"So are you, Fred."

He put her suitcase in the back and let the door fall shut. "Itll be three-quarters of an hour before we pick up the boss. Want to sit up front?"

The chaufeur was twenty-seven or twenty-eight, rather short, thick-shouldered and stocky. He had muscular wrists and lean hands. It occurred to the girl that if the car had been a horse, he'd have been a centaur. They moved toward the lake and turned north on the outer drive. It was soft going.

Alice Brennan stuffed her fists into her jacket pockets and watched the whitecaps. The lake and the city seemed to suffer a diminution in size. They fell into place on a mental map that had to be smaller scale than usual, to include distance. She recognized the change, the familiar feeling called "getting an early start," the uprooting and relaxing of the mind and the projection of the mind's eye forward along a chosen route. "This is the last trip, I guess," she murmured.

"First and last for this baby," Fred said, patting the wheel. "Four hundred miles." This was score. "Well, 111 be glad to see her get a little dust on her tail, anyhow."

The girl smiled.

He took his chaufeur's cap off and laid it on the seat between them. "Wait'U you see the trail we got to take into the camp. Some fun for fifteen miles."

"Secluded, hm?"

7

"Pretty wild. But it's a nice place. YouTl like it." His voice went off tone on that, just a little awkwardly. "Too bad he's got to close it up ifor the duration," he went on, "but I dunno how you'd get in there without a car."

"I'm supposed to help him make an inventory."

"Is that so?" Fred skipped the faint self-derision in her tone and was politely the recipient of news. "Well, I guess the caretaker's going to move all the way out, then."

"The caretaker's got a wife, hasn't he?" she said rather flatly.

"Oh, sure. She's a nice old dame."

"Is she?"

Fred said softly, "Don't worry."

"Oh, I'm not worrying." She crossed her legs. "Have you got a match? Gosh, I'm sleepy."

"Go ahead, take a nap," he suggested. The car floated. The windows were closed against the morning chill. Soon they were above Evanston, sliding qiiiedy between the varying walls and fences that hid rich men's houses from the thoroughfare. The morning was perfect. Their comfort was absolute. The car went like thought.

"She's running sweet," Fred said. "Aw, something's the matter with me." He thumped the wheel. "Why should I feel so sorry? What business have I got feeling sorry for Innes Whitlock?"

"It's not for him. It's for the car," the girl said softly. "It's so darned beautiful and American. It nearly made me cry."

For a second the car itself faltered, as if with emotion. Then Fred said, with an air of banter. "Kind of sentimental, aren't you?"

The girl's face hardened. "I haven't been sentimental," she said clearly, "since Saturday morning. What are you going to do when the tires fall off and you're out of a job? Enlist?"

Fred smiled, showing a gold tooth far back on the right. The wrinkles radiating from the comers of his eyes looked weathered in. "I'd just as leave go in the Army," he said, with an air of being reasonable, "but I broke my foot a few years ago and the Army don't trust it."

"Broke your foot?"

"Yeah, playing football. But the funny thing is, Mother

Nature has put in a bundh of new bone there, makes it twice as strong. Or that's what the doctor said."

Alice, by opening her eyes wide, knew how to look very innocent and baby-doU-like. "You mean the Army won't trust Mother Naturel"

"Well,'' said Fred, "the Army makes a pair of shoes the same size as each other."

Her eyes narrowed again with laughter. "What will you do, then?"

"rm not worrying. I'll stick to Innes."

"Um-hum."

"He can get me a job if he wants to. A man with a million dollars has got a lot of contacts."

"How right," Alice said in a low voice. "How true! And you've got a contact with a million dollars. Hang onto your contacts. They matter. Three kinds of people, that's all. A few top people who've got something. A lot of other people, the smart ones, trying to make contacts with the top ones and get some of what they've got. And then a whole lot of dumb bunnies who don't know where the percentage Ues. Do you know about percentage, too?"

"Huh?"

"Why, that's what you ask yourself. Is there any percentage? That's the way you tell who your friends are, whom to speak to, whom to be nice to, whom to . . . You be smart, Fred. Always watch the percentage."

"Your philosophy of life?" Fred inquired politely.

"Yes."

''Since Saturday morning?"

"Never mind since when. But I learn fast. I'm quick," she said viciously.

Fred said nothing. They were close to Lake Forest, now, where Innes Whitlock lived; and he turned from the main thoroughfare into a winding road and let the big car loaf along, not hunying.

Alice chewed on her lower lip. In a few minutes she said, "Excuse it, please, Fred."

"Yeah, but listen," he said, as if the argument were his, not hers, "it stands to reason you got to look around and see what goes on. So the whole world's full of chiselers. Chiseled themselves into a sweet mess and still chiseling. You can't get away from it. You look out for yourself and

don't get fooled. That's what I say."

"Sure," she said, "that's what I say."

"Why stick your head in the sand and make out like virtue is rewarded when . . ."

She turned her head sharply. "Who said anything about virtue?"

"I used the wrong word," Fred said. "I didn't mean that." He stopped the car. "Look, kid, I don't want you to get me wrong. But I wanna ask you something."

"Go ahead." She looked him straight in the eye. "We're on common ground. We both know Innes has got a million dollars."

"Well, I just wanted to know. With the three of us going off on this trip today, do you want me to stick around? Or do you want me to disappear once in a while?" Her eyes fell. "I'll do what you want," Fred said. "You understand? I dunno what's in your mind. I thought if I asked, then I'd be able to do what you wanted."

She looked him full in the face again. "I don't think I get you wrong," she said. "You're just asking."

"That's right."

"Well, I'll tell you. Object matrimony."

"Uh-huh," he said. He slid back in his seat. He didn't look relieved.

"I know damn well he doesn't need his secretary to help him close that camp. I think he's working up to . . . what I . .. Well, if I'm wrong"—she shrugged—"heaven will protect the working girl."

"If you're wrong," Fred said, grinning at her, "maybe I could run a little interference for heaven, hm?"

"You think I'm wrong?"

"I dunno," he frowned. "Innes is no wolf. He's been sued for breach of promise twice already." Alice threw her head back and laughed. "Yeah, but . . ."

"Look," she said, good-humoredly, "I know . . ." She couldn't explain the subtle basis for her certainty that in Innes Whitlock's mind she was not to be trifled with. "Call it woman's intuition," she said lightly. "I can always

scream."

He looked at her. His hands were quiet on the wheel. He seemed merely thoughtful. "Thanks a lot, Fred," she said suddenly.

''That's all right. I hope you make it. Money's the only thing that can help you much in the world today. Maybe that won't be for long, but for a while— Say, if I knew a dame with a million dollars, Fd make the same play."

"Who wouldn't?" Alice murmured.

He touched the controls, delicately, and the big car slid on. In a moment or two it hesitated before a pillared gateway.

"Well, get dignified," Fred said, putting his hat on. "We're here."

Alice stiffened her back. "Look here," she said rapidly, "I shouldn't have said all that to you."

'That's right, you shouldn't," he said cheerfully. Then his face changed and his voice was wooden. "This is the house. Miss Brennan." The car stopped and he got out smartly, in one movement.

The broad white house door sprang open. A manservant appeared with luggage. Fred went briskly around the car and opened the tonneau door. A woman in a maid's uniform appeared with a thermos bottle. Innes Whitlock, a rug over his arm, burst out of the doorway.

"To the minute," he said, glancing gracefully at his wrist watch. "Good morning, Alice. How are you? Isn't this a day! I've got a picnic basket Look here, you've got to ride with me."

The little mustache that tossed on his upper lip made him look as if he were pouting. Alice became animated and moved to the back seat. The servants bustled. They stowed things in the trunk. "Are you warm enough, Alice? Tuck in the rug, Fred, on that side. That's it" Fred tucked the rug around her with skillful hands.

Innes's rather short pink nose sniffed the morning. He seemed somehow to give it his blessing. His rather plump white hand made a tiny gesture. The adventure had his permission to begin.

They stopped to eat their picnic lunch before noon. A little after, Alice stood in the sun on a weedy margin of the country road. The Ixmch basket, all neatly packed again,

was in her hand. Everything about her seemed particularly vivid: the pattern of old leaves and dead grasses, the green pushing thurough, the contour of the ground, higher behind her, going down to a weed-choked ditch between her feet and the car. It was just a roadside, unloved and untrodden. Even the broken fence above bounded a strip of land no one had cultivated. It was an undistinguished spot

Fred was walking back along the road, kicking the dusty grass. He saw her and came quickly to take the basket. For a second his brown eyes asked her a sober yet impertinent question.

There was the tiniest flicker, a mere flame of reproach in her blue glance, and then she turned. Innes blundered out of the brush with three wood anemones in his hand. "Oh, Mr. Whitlock," gushed Alice, "aren't they sweet! What are they?" .

That was an "if' moment. Every so often there is a point at which, if one looks back, the course of events can be seen to have taken a turn. Most moments are details between fixed points. This one was a point from which Alice's life branched off in a totally new direction. If Fred had not asked her that quick, impudent question with his eyes and if she had not, perversely, refused to answer it—partly, of course to punish him for the impudence—if she had not called out in that false voice, meant to deceive, "Oh, Mr. Whitlock . . ."

At that moment, she might just as easily have called him Innes because she had been engaged to marry him for fifteen minutes.

He'd waited no longer than after lunch. He'd put his enameled coffee cup down, reached for her hand, and said, "Alice, my dear, I want you to marry me." It was very simple and rather touching. She had been able to turn to him with real surprise and say, "Why, Innes! I'm glad you do." Innes had, thereupon, kissed her. It was a few minutes before she could say lightly, "Of course you know I'm marrying you for your money?" To this Innes had replied with a happy sigh, "Just so long as you marry me ..."

Innes had come through it very well, Alice had felt. She was a little ashamed of telling the plain taith in so deceptive a manner. Therefore, it was perhaps the first stirring of a sense of loyalty to a new alliance that made her withdraw from even the shadow of a conspiracy with the chauffeur.

If marks an alternate trail, along which one can see no farther than the first comer.

"What's the matter with it?'' asked Innes impatiently, some hours later.

"Nothing I can't fix m an hour," Fred said. "Sorry, sir. Shall I limp into the next town?"

"Will it limp?"

"Just about."

"Where are we?"

Fred reached for his map. ''Sixty-five miles to camp yet. We're ten miles out of Ogaunee, sir."

"Oh, lord," Imies groaned. "Don't tell me."

"If you and Miss Brennan don't mind just sitting here I can get busy right away. I thought— "

"Yes, yes." Innes pasted his hand over his brow with artistic weariness. "Are you cold, Alice?"

"Chilly," she said She felt exhausted, mentally and spiritually. The long afternoon drive had been a strain, she wasn't quite sure why. She thought perhaps their swift flight along the roads was too comfortable and oddly static. "I'm a little tired of riding. Can't we walk up and down while he fixes it?"

Innes said, "No, no. Better try to make it into Ogaunee, Fred. We'll get this girl warm. Stay for dinner if we're asked."

"Asked?" Alice said, startled.

"My sisters' house is in Ogaunee. We'll stop in there."

"I didn't know you had a sister."

"I have three sisters," Innes said. "They still live up here. It was my father's house. My dear, I'll tell you a secret. I was bom in Ogaimee, MicWgan."

"Oh?" Alice invited more. ' "I must confess Fd planned to skip by, this time," he went on uneasily. "They're another generation, really. Half-sisters, you see. My father was twice married."

Alice felt she ought not to say "oh" again, so she kept quiet.

"You don't mind, do you?"

"Mind? Of course not."

"It'll be more comfortable than sitting here," Innes said a little doubtfully, with an effect of gnawing on his mustache. Then he smiled. "We'll be some excitement for them." He patted hex hand.

The big car crept forward, complaining. Alice knew nothing about the insides of a car. She looked at the back of Fred's neck and wondered if it hurt him, this humiliation of his Proud Beauty. She herself sat ridiculously tense, as if the car had pain,

"This isn't going to damage the engine?" demanded Innes, who evidently knew nothing about the insides of a car either.

"No, sir," Fred said stolidly.

For a long time no one spoke, as if the car's plight cast a spell of silence over them. Only Innes cleared his throat from time to time, but he never quite said anything. Alice thought it tactful to ask no questions. She simply sat, and slowly began to wonder what it was he felt he ought to say and couldn't

It was a curious ten miles, full of reluctance. Not the nightmare quality of trying to get to a place and always failing, but an equally nightmarish feeling of taking much labor and some pain to get to a place where one didn't want to be. Ogaunee was a gash across the smooth face of their plans. Furthermore, it required bracing. One had to brace oneself. Alice felt that.

When at last they crawled past a house or two, Innes burst into speech. It was his home town, after all.

"This is iron-mining country, you see. This is the Menominee Range. What they do here is underground. Up on the Mesabi they strip off the earth and take the ore out of an open pit. Makes a mess. But it was pretty here when I was a kid. My father owned the land all around and brought in Eastern captial in the old days. There's a shaft-house; see? That's Briar Hill."

The wounded car crept aroimd a curve. Ahead, the road dipped and staggered over a kind of earthen bridge. On either side of the built-up causeway the ground fell precipitously into two great deep pits, down the far sides of which was scattered debris, as of shattered houses.

"Good heavens! It's fallen In!" cried Alice. Innes said carelessly, "Well, you see, when they mine

underground they honeycomb the place. Where the ore comes out, they prop up the roof with timber and go deeper, down to another level. Of course, later, when the ore's all gone, the timbers rot, I suppose, and collapse."

"And the earth falls in!" Alice said, awestricken. "The houses, too?"

''Same of them were over the mines." "But how terrible!"

"Oh, no. Nobody gets hurt. It's not like an earthquake, you know. It's slow. It just sinks."

"I still think it's terrible. It isn't going to fall m any more?"

"No, no. Although they have to keep filling in this road." She looked at him, horrified. "Oh, it's all over now. Don't worry. These mines were played out long ago. This is what you might call a ghost town." "Is it, really? Like the ones in the West?" "Not so romantic," said Innes. "Why do people stay here?"

"I do not know." Innes dropped his guidebook manner and was personally vehement. "I wouldn't." Then, with that curious reluctance, ''Of course, my sisters . . ."

"I don't know if she'll take the hill, sir," Fred said over his shoulder, "but I'll try."

"Look," Innes said, pointing out his window and up. "That's the house. That's the back of it."

Alice leaned, almost lying across his lap. "The house where you were born?"

"Yes." He supported her shoulders tenderly. "It was quite a place once, if you can believe it."

Alice saw a whitish structure above some rocks which rose out of the side of the pit and went up. She had goodeyes. "What a queer place for a door," she said. "Why, there's a door way up in the wall that just leads right out into space."

Innes looked, too. His mustache brushed her cheek. "There used to be a back porch. It was torn down years ago. Got pretty shaky. Lord, I'd almost forgotten. I must have been about ten."

She tried very hard to think of Innes as about ten, to see his much-shaven face soft and hairless, his smudged eyes fresh and naive; to pare away hi her imagination the central paunchiness of his figure, the settled and not un-feminine width of his hips; to take out of him the starch that thirty years had put into his body and mind, to see him lithe and free and about ten. It wasn't easy.

"You had a rocky backyard to play in," she said, with the best sympathy she had.

"No, it was a pine woods," Innes said dreamily. "All this land was higher than the road is now. It just sloped off, all trees. I used to know the paths. I used to lie on the ground and hear them blasting, deep under."

Alice squeezed his hands. For a moment she thought she understood why he was reluctant to revisit Ogaunee.

"You never grew up in a mining town. You never heard the steam shovels puffing and snorting all night long. Or lived by the whistles. Well it's dead now. I . . ."

They were across the pit and in the village. Almost immediately they turned sharply to the right and began to climb. Innes forgot his reminiscence. "Look here, Fred, we can get away right after dinner?" He spoke not to a servant, but to a man who knew the answer.

"Sure we will. Why wouldn't we?" Fred answered boldly, like a man who did know and could reassure another.

Back of them, to their left, and soon below, the town lay wholly exposed. A block of frame buildings leaned together with a gap here and there, like a tooth gone. Dwellings marched evenly in a few rows, then broke ranks and scattered. A few were lost in the hills. Across the far end, a line of railroad track made a clean edge between town and swamp.

Alice caught this maplike impression out of the comer of her eye. She had to help will the car up the hill when it shuddered and seemed to fall, when it took heart, then seemed to slip and hang on the brink of backward motion, then coughed and pushed weakly up with scrambling wheels, catching for a hold.

Once Fred said, "The cottage, sir?"

"No, no," Innes said, pushing on the floorboards with his suede-shod feet "Go on, don't stop, go on."

Fred leaned forward and by sheer stubbornness seemed to call out a spurt of power that lifted the car up the last incline and rolled it, dying, to the level drive before the door.

Innes sighed. "O.K., Fred. Bring Miss Brennan's bag. She'll want to freshen up. Then you can get busy."

The house was of wood, long painted white. Its facade was like a face. It had eyes, nose, and mouth, if one happened to notice. Alice looked up and saw the upstairs window eyes seeming closed under raised brows and thought the expression on the face was haughty and self-satisfied.

As they stood on the porch after Innes had turned the metal handle of the old-fashioned bell, she could see through a window to her right the outline of a pair of shoulders, tremendously broad. It was no more than an outline, dim behind the lace; but she knew it wasn't a woman.

"Are your sisters married?" she asked Innes hastily, ready to revise an unwarranted impression.

He looked shocked. "No," he said. "Oh, no, none of them." His small mouth under the mustache remained rounded for speech, but again he did not say what more was in his mind, though Alice waited. On this unfinished, even unbegun, communication between them, the door opened.

The woman who opened the door seemed, at first glance, pop-eyed with surprise. She was big-boned and rather thin, although her face was round and firm and her features melted into one another without any angles. She looked, thought Alice, like a Botticelli woman, but not so fat. There was a convex swelling under her throat, and the pop eyes were permanent. "Why, Mr. Innes!" she said.

"Hello, Josephine." Innes affected a great joviality, as if he were playing Santa Claus. "Alice, this is Josephine. The car's broken down, Josephine, so I guess we're here for dinner, if you can find anything for us to eat. Are my sisters .. . ?"

The woman nodded. She made a fumbling motion with her cotton dress as if she were drying her large bright-pink hands.

"Tell them, will you?" urged Innes. "Come in, Alice.

Put the bag there, Fred." Innes asserted himself as if he needed to prove that he belonged here. The center hall lay between two arches. He led the way through the velvet-hung opening at the right. The house seemed quiet and deserted. A new-laid fire was burning in the grate, the kindling just caught But there was no one there.

The room was warm and a little stuffy. It was fuU of furniture and knickknacks with rugs overlying other rugs on the floor. Every table had a velvet cover and a lace cover over that. The place had a stuffed and cluttered elegance. Eveything in it was elegant of itself, to the point of absurdity. A Victorian room, Alice decided, and no imitation, either. Yet, because it was the real thing it impressed her. The conviction that these furnishings were still elegant was hard to resist. Someone so patently thought so.

"Sit down, my dear.'' Behind them, Fred had vanished. Josephine had gone upstairs. Alice loosened her jacket. "rU ... er . .. just fetch Gertrude." Innes made for a door in the wall opposite the front of the house.The curiosity that had occupied Alice until now was touched with panic.

"Do I look all right?" she said.

Innes turned, not his rather too bulky hips, but his head only. His eyes appealed to her as he looked backward over his shoulder. "It doesn't matter," he said, and his reluctance broke like a crust. "My sister Gertrude is blind."

Alice sat still, feeling the shock ebb out of her nerves. Innes had left her. She was quite alone. She felt submerged in this unfamiliar house, drowned without an i-dentity. Her eyes went to the fire, which at least was familiar and alive.

Alone, she should be gloating, "Goody, goody, I'm going to marry a million dollars." No wonder she felt strange and out of herself. Nothing to worry about. No living to make. Living's all made. Quick work, Alice.

Only last Saturday morning Alice had sat in her office with no dowry, nothing to swap in the marriage market, no money, prestige, influence, nothing to bring to her wedding but the bride. Now, on Thursday, slie'd swapped just that for a million dollars. Show him. Show Art Killeen. Two could play.

Quick work since Saturday morning when he'd come in-

to her office and sat on her desk with his leg swinging and said, "I'm courting a North Side debutante these days, you know. I'm really working at it." Said it in laughter, given the message kmdly, lightly, in laughter: "Better give it up, Alice. It wUl never be." She was ashamed to think he'd known she thought . . .

Oh nonsense! Why shouldn't she have thought they were going to be married, she and Art Killeen? They were in love. She'd been so dumb she hadn't known. No percentage in love. A silly, unprofitable thing, so often an economic or political mistake. Leading, however, in her case to a million dollars. Had it not? Would she have come from New York to Chicago if Art Killeen hadn't thought it such a fine idea that he'd got her the job with his pet, his wealthiest client?

A woman sees her husband's lawyer sometimes.

"I am looking," Alice said to herself solemnly, "into what the French call an abyss!" Muscles at the comers of her mouth flattened involuntarily. Well, if she could smile she must be getting better. Or was it wild hope running like a weed to spring up though she'd cut it down?

She had heard no sound, but she lifted her eyes and saw a man in the room. He was enormous. His great fat thighs strained in a pair of filthy dark trousers. A green flannel shirt, torn at the armhole, was open at his bullish neck, showing a stretch of dirty underwear. His hair was lank, black, and long enough to show below his ears. His skin was brown, and his face glistened as if it had been oiled. His eyes were a sharp black, without brown or yellow. He stood in the middle of the room, looking at her without much curiosity. She could have screamed.

Then she saw that he carried a hod of coal. She shrank back in her chair and said nothing. Soon he walked silently to the grate, knelt, and began to pour coal upon the fire. She saw the muscles of his broad shoulders working under the fat. He was not a Negro. His features were thick, but the mouth was firm, and there was a flaring line from his nostrils to the tip of his nose that was both foreign and familiar, though she couldn't name him. She couldn't tell what he was. He knelt not two feet from her, and she became gradually aware of an odor and was nearly sick. The man put forth a scent, like an animal.

In a moment he had finished with the fire. He rose and was gone as indifferently as he had come. But before he left, be poked his dirty fingers into a box of candy that lay among the many trifles on the mantel and casually took two.

Alice sat still, her heart pounding in her throat.

In a moment or two the door in the back wall opened, and Innes led forth a straw-colored lady. "Gertrude," he said with anxious social sweetness, a tone that poured soothing oil upon this meeting and begged them both to be kind for his sake, "this is Alice Brennan. Alice, this is my oldest sister.''

"How do you do. Miss Whitlock," said Alice, rising.

The woman turned her face toward the voice. She was somewhere between fifty and sixty years old. Her hair was a pile of pale straw, severely drawn back from her thin, bloodless face. The eyes were as pale as the rest of her, and even her brows and lashes made no easily discernible marks, so that the face was blank, as if eyes had been left out of it altogether. Her lips, too, were unreddened by blood or anything else. Yet there was a certain haughtiness about her tall, stiff figure and the impact of a personality.

"I am glad to make your acquaintance, Miss Brennan," she said in a rather high voice that was however, not thin, but rich in flute tones. It held a deliberate sweetness, faintly affected. "Innes tells me you have had trouble with the car."

"Can you give us dinner, Gertrude?" Innes said with a combination of humility and demand. "If not, I suppose we can . . ."

"Certainly, we shall be glad to give you dinner," Gertrude said proudly, almost as if she were offended. "Speak to Josephine."

"Well I have, but I will again. . . ." Innes was awkward. This pale sister seemed to unbalance him, as if he saw himself in two lights, once as her young and somehow humbled brother, once as Innes Whitlock, the successful man, and he couldn't make the images blend.

Gertrude dismissed the domestic problem as if it didn't concern her. She moved forward to find a chair. Alice sent a questioning look to her fiance.

limes began to chuckle. "Gertrude is pretty marvelous," he said heartily. "Gertrude, I can see her wondering how on earth you find your way so well."

Alice, who had been wondering nothing of the sort, saw with surprise that the woman's thin lips smiled, almost triumphantly. "But I know my way perfectly in this house," she said. "Never worry about that." She seemed to unbend a little as if this topic were welcome. "I have been totally bluid for many years, but I do not let my affliction prevent me from moving about this house with complete confidence."

"Why, that's wonderful!" breathed Alice. "I do think that's wonderful. Miss Whitlock."

Innes beamed. Alice knew she'd caught on quickly, that this was what she ought to be saying.

"I simply resolved," Gertrude said and Alice recognized a worn quality in the phrase, "that I would never be a burden. Nor have I been." The blind woman sat down in a chair near the fire. She picked up an elegant box lying close to her hand. "Do you smoke, Miss Brennan?" she said pleasantly, holding the box quite accurately in Alice's direction.

"I do, thank you." Alice reached out her hand. Then she saw with dismay that the box was empty. The blind woman was showing off, and she had made a mistake.

For the space of half a second, Alice hesitated. Then she fumbled in her jacket pocket with her left hand. "I don't like to take the last one," she said with an apologetic and rather timid laugh. She dipped her hand into the box, letting the woman feel its pressure.

Innes leaped forward with a match and lit the cigarette Alice had pulled from her own pocket. "Let me," he said gallantly. "Gertrude is marvelous, really, isn't she?" His eyes congratulated Alice and thanked her, too.

Alice leaned back with a little glow in her heart. She was pleased with herself for having thought so quickly how to save the blind woman's pride and still warn her not to make the same mistake again. Having done Gertrude a service, in a way, Alice felt warmer toward her.

But Gertrude said, rather petulantly, "It ought to be full. Josephine is not quite all there is to be desired in a servant. It is very difficult, you can imagine . . ."

"Yes, indeed," murmured Alice.

"The girls who are willing to go into domestic service are quite untrained," Gertrude went on, "and quite im-trainable, I'm afraid."

Alice murmured again. The conversation seemed to her to have taken a queer turn. It was peculiar to sit here and discuss Gertrude's servant problem when the news of the moment was surely Innes's unexpected arrival and Alice's introduction to this house. But, she told herself, Gertrude Whidock's world was dark and limited.

"Josephine does very well, Gertrude," Innes said soothingly. "The house looks well. Just as it always did."

Gertrude sighed. "Innes," she said, "I wish you would speak to Maud and Isabel. I do not understand it. I, alone, am maintaining the house again. I am perfectly willing to do so. You realize that."

"I know," Innes said angrily. "I know aU about it." Faint pink came up under his skin and his eyes looked sullen.

"Yet I seem to have less and less," Gertrude went on, scarcely heeding; "and really, we cannot do without servants. Even if it would look well, which it would not."

"Good heavens, of course you can't do without servants," Innes cried. "Tell me—the same old thing, I suppose?"

"They say they cannot share," Gertrude shrugged. "I haven't doubted them. I don't care to discuss it, naturally."

"You haven't gone into your capital?"

"The bank will know. I know nothing about that sort of thing." Gertrude Implied that no lady would.

Innes clicked his tongue.

"But how sordid," Gertrude said suddenly. "Forgive me, Miss Brennan. This must come under the head of business and you do imderstand business, I suppose. I don't see Innes often. I must snatch a moment."

"Tm a bad boy," Innes said with his pout. He had a way of being whimsical about his own shortcomings.

The blind woman pursed her dry lips. "Of course, Innes is Stephen's son but not Sophia's," she said, as if this explained something. "That is Sophia, hanging over the mantel."

Startled, AKce looked up. Sophia was, indeed, hanging on the wall but looking as if she had never been alive at all. A pale oval face, stiffly done by a bad artist, it had a kind of crookedness to it, as if the artist had lost control of what little skill he had and gotten the perspective wrong. One eye looked insolently at the beholder, as eyes do in such portraits, but the other rolled a little wUdly, as if it looked elsewhere. No, not elsewhere, but inward, as if half the woman dreamed.

"An excellent likeness of my mother," Gertrude said complacently.

There was sound on the stairs of feet plopping flat on each step and a dumpy figure appeared in the arch. Innes stepped quickly forth, took the newcomer's hand and swung it, making a little bow at the same time. "My sister, Maud."

The dumpy one chuckled. "Surprise, eh, Innes?" she said in a rasping voice, a queerly masculine voice, harsh and unpleasant and toneless. "You don't drop in like this so often."

Alice thought immediately of the Duchess in Through the Looking Glass, or was it Wonderland? Her nose was an untidy pug. Her hair was a rat's nest. Alice found a moment to wonder how anyone could deliberately go to work and arrange a head of hair like that. It was snarled and twisted into a pagoda full of hairpins, and there was no logic in it. Maud's skin was gray and hung on her face in folds. She wore a black dress embellished with tags of lace as illogical and haphazard as the arrangement of her hair. Her fat ankles were bound into high white shoes which, Alice saw, not without shock, were dirty and yellowish. She came closer, and her lively little gray eyes peered curiously at the girl.

"How ja do?" said Maud and stuck out a slab of a hand. The puffy flesh ended in dirty fingernails. Alice winced. Her nostrils twitched, then she stopped breathing; for from sister Maud arose an odor, definitely an odor; and, although fainter, it was the same rank animal smell she had noticed before.

"How do you do. Miss . . . Miss Maud," Alice foundered, looking desperately to Innes. "Is that proper?" She heard herself giving a very nervous litde laugh. "I can't

very well call you both Miss Whitlock. I . . ."

But Maud was looking at Innes, and her harsh, unlovely voice cut through Alice's sentence and stopped it.

"Who's the girl?" she said. "Where'd you find her?"

Blood rose in Alice's face. The blind woman said quietly, ''My sister Maud is quite deaf. Miss Brennan. She doesn't hear you at all."

Alice had trouble to draw her breath smoothly. "Thank you," she panted. "I didn't know."

"She is really rather helpless," said Gertrude contemptuously.

Innes had been spelling on his fingers. Maud's little eyes turned to the girl. They were bright and peered from folds of her grayish flesh.

"Secretary, eh?" she said bluntly. She waddled over to the chair in which Alice had been sitting. She collapsed into it. Her fat little body simply melted its bones and fell down. She stretched her ugly legs out and looked up at the mantel. Innes reached for the candy box. He did this automatically and handed it down. Maud dipped her fingers in.

"Have some candy?" she said to Alice, who shuddered "No." The woman stuffed three pieces into her mouth and grinned at the same time.

"Look here, Maud . . . Excuse me, Alice." Innes snatched a pad of paper from the incomprehensible folds of the woman's dress and produced a pencil. He scribbled.

"What's that?" Maud said, regarding what he had written without much interest. "Oh, financial, eh?" She grinned. "My financial position. Innes, you're a card."

He tapped the paper with his forefinger, impatiently. He was quite ready to dominate this sister.

"I've still got the two Liberty Bonds," Maud said. "Isabel hid them on me. " She went into rusty laughter.

Innes pantomined.

"Oh, I dunno," Maud said. "Spent it, I guess. Eh?" She took another chocolate. "It goes," she said slobbering and sucking in the overflow with a loud slupp, "Isabel's the one. She never spent an easy cent in her life, and it goes just the same." Maud heaved with mirth. "Makes her pretty mad. Should think it would."

"This," said Gertrude with an air of confidence to

Alice, "is extremely distasteful to me."

"And to me," limes said, rather grimly. His gaze was fixed on the deaf woman. "I warned you the last time. I'll make up no more deficiencies. Fll expect all your papers and accounts within the week."

Gertrude stiffened. "I'd prefer to go on with the bank, as usual," she said icily.

"Don't know what you say," rumbled Maud. "Write it down."

Innes gnawed his mustache. "Later," he said with a worried glance at Alice. "Gertrude, you must see it's to protect you."

She lifted her pale chin. "I am no one's burden."

"Innes . . ."

The third sister stood in the archway. She was not as short as Maud nor as thin as Gertrude, but medium tall with a plmnp breast like a pigeon. Her hair was a litde darker than straw and ballooned aroxmd her face like an inverted umbrella, then subsided in a round mound on top of her head. Her complexion was mottled, but she had a kind of meaty color. Her features were sharp, but because they were embedded in a roimd-jowled face, die effect was not sharp. Her eyes, Alice noticed with a shock, were like the eyes in the portrait. One watched and one dreamed.

"Isabel, how are you?" Innes was faintly hostile. "This is Alice Breiman, who's with me. My secretary. Alice, come meet my youngest sister."

Isabel smiled with her lips together. Impulsively, on ac-coimt of the smile, Alice held out her hand. Quick, but not quicker than the veiled dismay in the woman's eyes, Innes ran his arm through Alice's and drew hers down.

"I was saying, Isabel," he said sternly, "that I shall have to do what I threatened to do and take over aU your business matters. I understand you are in a financial mess again.''

He was ready to dominate this sister, also, but she was slippery. Isabel's eyes slid sidewise and down. She didn't answer. Instead she said, "You're always welcome, of course," in a kind of brisk whme; "but I do wish we had known, Innes ..."

"We couldn't very well warn you," Innes defended himself haughtily. "The car went wrong. That wasn't our fault."

"Well, I do hope you won't mind having just what we were about to have ourselves." Her thin smile turned to Alice. "You see, I think dinner is actually ready. And it's so late, you know . . ."

"Please don't trouble about anything," said Alice a lit-de coldly.

"Give us pot luck, Isabel," Innes said, "for heaven's sake."

Isabel's smile remained much the same. "Of course we are very glad to see you both." Her voice had no range. "Perhaps Miss Brennan would care to wash?" Isabel put her left hand, which was small and nervously strong, on Alice's arm. "Is this your bag? I'll call Mr. Johnson."

"Please don't trouble."

The naUs on the hand were very long. The fingers tightened. Alice stood still in the woman's grasp. Her heart began to pound again.

Isabel let her go suddenly and turned away with a quick and somewhat crooked motion of the body.

Innes said, in a low voice, "Isabel's lost her right arm. I ought to have told you."

Then Alice saw the gray kid glove covering stiff artificial fingers on the hand that hung at Isabel's side as she moved crabwise across the hall.

"Yes, you ought to have told me," she said quiedy. "You really ought. Why didn't you, Innes?"

He looked as if he would melt when she raised her reproachful eyes. Alice saw his lower lip push out. With sudden insight, she knew that in a moment he would feel the punishment to be greater than the crime. She looked at this petulant millionaire, the man she was goijig to marry, and she saw her cross of gold.

"Never mind," she said breathlessly. "I only hope I didn't offend her. Oh, Innes"—she made her eyes round—"do you think I have?"

"No, no, of course not," he said fondly. "Of course not, my dear."

It didn't matter much, Alice saw, if Isabel was offended, as long as Inncs needn't feel uncomfortable about it

"Will you take the yoiing lady's bag upstairs, Mr. Johnson?" Isabel whined.

Mr. Johnson was the gross man in the dirty flannel shirt. He followed her into the hall and scooped up Alice's bag as i£ it had been a ping-pong baU. "Sure. Where do you want it?" His inflections were pure American. His teeth, some of them, were gold. His black eyes rested on Alice briefly.

"In the little guest room," Isabel said, in her tone of perpetual worry. "The heat's not on in Papa's room." She put her claw on Alice's arm again. "Mr. Johnson will show you."

Alice wanted to talk and scream like a frightened child. She did not want to go off upstairs with that outlandish creature named, of all incongruous names in the world, Mr. Johnson. Innes saved her.

"Wait a minute, Alice. Come in here, Isabel. For just a minute. I have something to tell you. All three of you. This is news, my dears, really news," Innes was being Santa Claus again, with the same loud, false, hearty good will with which he had entered this house. Gertrude cocked her pale head. Isabel drew within the room with her sidewise step; and Maud, as he tapped her shoulder, turned her shrewd eyes up at him.

"Alice and I are engaged to be married," he said. And then, without sound, he mouthed the words again for the deaf woman.

It seemed to Alice that sound disappeared from the world. The shattering stillness and Innes's mouth working silently seemed to prove that her own ears had failed her. Gertrude, sitting with her head cocked, did not move. Isabel put her left hand out and drew it back. Alice thought she must have cried out, yet because of her own sudden deafness, she had not heard the cry. Not until the fire muttered was she sure it was a real silence that enclosed them.

Maud broke it. "Married?" she croaked. "You and her, eh? Is that so!"

"No, no." Isabel reached with frantic haste for the

paper pad. "Not yet. Engaged." She said it furiously and she wrote it furiously, with her left hand, pressing hard. The smile on her face was a frozen thing.

"How very interesting." The blind woman's voice tinkled coolly. "Well, Innes, you have my best wishes, of

course."

"It's pretty good for an old bachelor like me, isn't it?" Innes said, rocking on his heels. Alice bit her lip.

"Engaged, eh? High time." Maud was accidentally apropos. Her eyes had a light of lewd speculation in them. Alice looked away, anywhere, looked at Isabel.

"Such a surprise," said Isabel, still plaintive. "My dear, we have quite despaired of Innes. Now we shall have to call you Alice. Isn't that nice?"

Her ideas seemed disconnected, as if her mind were elsewhere. But her smile was blooming.

"Brennan," said Gertrude delicately, as if she tasted it. "B,r, e, double n?"

"A,n," finished Alice. It seemed absurd that her first and only remark should be two letters of the alphabet. But they fell from her lips, and nothing else came.

Maud said gratingly, "Innes, you old devil," and slapped her thigh.

"We think we're going to be very happy," said Innes, foolishly loud. "Don't we, darling?"

Alice's shoulders were stiff and unyielding under the curve of his arm. She could not meet that mood. Could not, and no graceful phrase would come.

"Beg your pardon." Fred, the chaufeur, spoke from the hall. He must have come through the back of the house. He touched his forehead to the sisters. "Thought I'd better tell you. I'm going to take her down the hill, sir, and have them put in a couple o' quarts of oil."

"You mean it's running!" cried Innes.

"I think she'll be all right now," Fred said stolidly.

"Good work. That's fine. Fine."

Alice drew out of Innes's arm and found she was trembling.

"Tell your man," said Gertrude, "that Josephine will find him something to eat in the kitchen."

"Thank you, ma'am," Fred said. "I'll be back in a few minutes."

He left the way he had come, not having looked at Alice even once.

Innes took her upstairs in rather a hurry, after that.

The servant, Josephine, came hesitantly to the parlor, looking backward and up toward their disappearing feet.

''Well, Josephine, what is it?" Isabel spied her..

"Excuse me," Josephine said in a hushed voice, "but there's veal in the meat loaf, Miss Isabel."

"Yes," she said, "yes . . ."

"And you know Mr. Innes. So I wondered."

"Oh, dear," Isabel said. "There's nothing else m the house. I really don't know . .. Perhaps he's outgrown ..."

"Don't you think," Gertrude said gently, "it was always his imagination? I should venture to say that if one simply didn't mention . . ."

"There's very little veal," Isabel said. "It's nearly all beef."

Josephine looked from one to the other.

Maud roused herself. "Why don't we have dinner?" she shouted. "What are we waiting for?"

Josephine grimaced and pointed upstairs.

"Don't know what you mean," Maud said stubbornly. "Where's dinner? Why ain't it on the table? Write it down."

Alice closed the bathroom door upon herself vnth sagging relief. Innes had kissed her in the hall. "You're so pretty," he said. "Well go on right after dinner. Right after dinner." He was in his spirits, but this was meant for comfort and as comfort she took it. Nevertheless, the bathroom was sanctuary. Here, for a few moments at least, she would be alone and away from any members of the Whitiock family. Perhaps she could get in touch with Alice Brennan, that independent young woman with such firm ideas of her own, who seemed to have evaporated, who seemed to have been for many hours a mere echo, an echoing mirror, a copy of something called a young lady.

As she splashed cold water on her face, she heard the whir of a starter, pulled the bliad aside, and saw the big gray car slip around a segment of the drive visible from this side window. It was running all right. The tail light winked at her.

Thank God, she thought, this is only for an hour or so more. Only for dinner. Right after dinner, Innes said, they'd be away. They would push on north. It would be dark, of course. She and Innes would sit side by side in the dark. They would come to the bad road in the dark and then at the end of it. . .

Alice leaned against the marble washbowl and looked at her fear in the glass. This was strange. Why must she tell herself these future steps, one by one? Because she could not see them. She couldn't imagine. Always, almost always, there persisted in her mind a view ahead, an outline of what was going to happen next. Vague, perhaps, but with clearly imagined spots in it. Arrival at a destination. Pieces of a plan. Pictures.

Only once before had she felt this blankness, this loss of the previewing sense, this chopping off of the antennae of her mind as they went forward into the future. That had been when she had been driving home from a dance with a gang, and she could not see herself getting home. The picture wasn't there. As now, she couldn't imagine it. It remained imimagined, an empty plan, without images, without faith.

That night the car had hit a tree and turned over.

Maybe I'm going to die, this time, she thought. Then, with a rush of her misery and her bitterness, "What the hell difference would it make?" she said aloud. And what difference would it make, indeed, when she was going to marry Innes Whitlock and not Art Killeen, ever?

In the long hall, on her way back, she met the chaufeur.

"Miss Brennan?"

"Yes." She kept her scrubbed face turned away.

''Congratulations." She turned her head angrily. His hand with the long thin fingers was held out to her.

"It's not proper to congratulate the girl," she said rudely. "Don't you know any better? Congratulate the man, but wish her happiness."

"Is that so?" he murmured mildly.

"Yes, of com'se," she said. It was not until she had closed the door of her room that she recognized his innocent mildness for the sham it was, and what he had said and meant came back to her like an echo.

He had meant to congratulate her.

Alice set firm and defiant feet on the stairs, going down, but there was a carpet. She could hear their voices in the parlor.

Gertrude's flute: "Of course Innes is Susan's son so it can't matter as much, you know. And indeed, it's possible that quite nice girls go into business these modem days.''

Isabel's monotone: "You know very little about it. She's very young. Much too young for Lmes. Innes ought...

Maud, crashing in: "Say, Innes'll have twins before the year is out. Litde heirs. Little sons and heirs. I think she's pregnant." Maud's laughter.

Isabel said, "Oh, be quiet!"

Gertrude, a soft soprano ripple: "Someone is on the stairs."

Maud, harshly: "Getting touchy, Innes is. And you won't get any . . . Eh? What?"

Isabel, in the archway: "Come in. Miss Brennan. My dear, I meant to say Alice, of course. Come in, my dear. Dinner will be served in a few minutes now. As soon as ' Innes is down. Did you find what you needed?"

"Yes, indeed." Smiling, her head high, Alice walked into then: parlor. They turned toward her. Their heads on their necks were three stalks in the same wind.

"And when do you plan to be manied?" said Isabel.

"Yes," said Gertrude, ''we are so interested. Have you set a day?"

"Say, Alice Brennan," said Maud, "that's your name, ain't it? When is the wedding? How soon, eh?"

"Oh, quite soon," said Alice carelessly. "There's no reason to wait." She took Maud's pad.

"Very soon," she wrote firmly.

About an hour after dinner, Alice pushed open the sliding doors of the second parlor, the room on the left of the hall, called the sitting room, and let herself through into the hall. Fred was just coming in by the front door. "Fred . . ."

He touched his forehead. "If your bag's ready, Miss Brennan . . ."

"Wait," she said.

"Mr. Whitlock wants to start."

"He's not going to start," she said belligerently. "Do you know who's the doctor here?"

"No, I don't, Miss Brennan."

"I'm worried," Alice said. She appealed to him with a little smile. "I really am. I never saw anybody as sick as that, just over the wrong food. I don't think we ought to let him go on." Fred was listening respectfully. "Do you?" she demanded.

"I couldn't say. Miss Brennan."

Alice stamped her foot. "Oh, stop it!" she cried. "This is no time for revenge."

Fred grinned. He suddenly stopped being remote and stood at ease, although he scarcely moved. "O.K." he said. "You put me in my place and now you want me to pop out again. Well, what's the matter?"

"Suppose we get him miles off in the car some place and then he collapses? I don't want the responsibility."

"Yeah, but he wants to go."

"He won't go if I make fuss enough. -Look, I'm just not going to go off with him unless some doctor says it's all right. Have you ever seen him like this before?"

"Yeah, once."

"What happened?"

"That time he was in bed three days."

"Well, you see? Here he's with his own family and in a house with beds and all, and I . . ."

"You don't want the responsibility," he said. "Well, I don't blame you. How about the girls? Why don't you talk it over with them?"

"They've said he shouldn't go. Where are they?"

"Search me. They were right here ten minutes ago. I was asking Mr. Johnson about number six."

"What?"

"The road."

"What road?"

"Concentrate," said Fred. "You know when you drive a car? Well, you pick a road."

"I'm sorry." Alice went over to the telephone that stood

on a little stand back in the portion of the hall below the stairs. ''I don't suppose there's more than one doctor in a town IDce this, do you?"

"If there's one," said Fred, "they're lucky."

Alice picked up the phone. When the operator answered she said, "Operator, can you give me the name of a doctor in ... in Ogaunee?"

"I beg you pardon," squeaked the operator.

"A doctor. I want the name of a doctor. I'm in Ogau-

nee."

"You mean Dr. Follett?" said the voice, suddenly human and sounding as if it were chewing gum.

"I guess I do," said Alice. "Can you connect me with his number?"

"Sure," the operator said.

"Miss Brennan," said Fred softly, ''you are sticking your neck out, if I may be so bold.''

They heard Innes calling, faindy, beyond the closed sliding doors.

A voice on the phone said, "Yes?" with a great patience.

"Dr. Follett? This is Alice Brennan speaking. I am at the Whitlock house."

The voice said, "Yes?'' very cautiously. Fred slipped into the sitting room, and Alice thanked him with her eyes.

"Mr. Innes Whitlock is here," she said crisply into the phone, "and he has been quite ill. I wonder if you could come and have a look at him?" "Who is this speaking?"

"Alice Brennan. I am with Mr. Whitlock. I am his . . . secretary," Alice said desperately. "Please come if you can, Doctor. Because Mr. Whitlock wants to drive on to his camp, and I'm not sure he ought to try it" "I see. You wish me to come there?" "Yes, of course,'' she said impatiently. "Do you know where we are? The Whitlock house. It's on a hill." Silence sung on the wire for a moment "Yes, I know," the voice said finally. "Very well." "Thaok you," Alice said with relief. She hung up the phone, looked at her watch. Eight o'clock. It might be sticking her neck out, as Fred had said; but she had a

strong feeling that this was no time to be passive, that it would be dangerous to keep her mouth shut and swallow her own opinions. The sisters thought he ought not to go. It was only Innes who insisted. And if she, Alice, kept still and let him have his way, she could see very plainly how her acquiescence would be open to blame if anything happened.

Besides, she resented illness, in herself and in others. She was impatient with it, and she had no confidence in her ability to take care of Innes if he should become violently ill again on some lonely road. The whole situation annoyed her very much.

How, she wondered, could a little veal in a meat loaf make anybody as sick as that? And how could a man susceptible to such a reaction eat meat loaf without asking what was m it? And, for that matter, how could those who knew his idiosyncrasy have the bad judgment to feed him veal, ever? Alice did a littie pacing up and down.

Presently the front door opened and Isabel came in, followed by a stranger, a dimipling of a little old woman, with pink cheeks and white hair, exactly like a character out of a book of fairy tales. She wore a shabby black coat over a cotton print dress and a velvet hat on the back of her head like a halo. She looked as if she had come in a hurry.

So did Isabel. "How's Innes?" She imwound her shawl with twisting shoulders.

"Better, I guess." Alice smUed uncertainly at the stranger.

"Well, Susan, you'd better see him and try to tell him he must stay here."

"I do agree with you. Miss Isabel," said Alice quickly.

The litde old woman said in a matter-of-fact voice, "You must be Alice."

"Yes, I'm Alice Brennan." Isabel, with queer discourtesy, had gone back to the closet under the stairs to put her shawl away.

"I'm so glad to meet you. Especially if you're going to marry my son."

''Sion!" Alice was so utterly astonished that she staggered.

Isabel said, "Susan was my father's second wife and In-

nes's mother, of course." She seemed aggrieved that there should be any surprise about it.

"I'm s-sorry,'' Alice stammered. "I really didn't know you lived here." Or anywhere, she might have added.

''I live in. a cottage part way down," said Ihnes's mother placidly. She made no move to take her hat and coat off. She was quite obviously transient here, not at home m the Whitlock house. "I'm so happy that you thought to call me, Isabel. Not only because of Innes." She smiled at the girl.

Alice smiled back, with reservations. There seemed to be nothing wrong with Innes's mother. She was whole of limb. Her eyes were bright and intelligent. She had a sweet and vigorous voice. The extraordinary pink cheeks were real, not painted. She looked a thoroughly pleasant old lady, but Alice was a burnt child and she was wary. She said nothing.

Fred opened the sliding doors. "Miss Brennan . . .'' Then his whole face warmed and glowed with smiling welcome. "Oh, hello, Mrs. Innes."

"Hello, Fred," said Susan. "How are you?''

"Fine. Just fine."

"And how's your mother?" she said, passing through the doors in front of him.

"She's fine, thank you," Fred said. "Just fine." The doors slid together.

Alice felt suddenly lonely and cold.

"Was that Susan Innes?" Gertrude's voice, lyrical with surprise, came to them from the back of the hall. The tall thin form moved with her swaying walk, toward them. She wore no coat but something cool and fresh that clung around her and reached Alice's senses, made her sure that Gertrude had been out of doors.

"Yes," said Isabel briefly. "I went to get her."

"Whatever for?" said Gertrude.

"Because Innes thinks he will drive to his camp, in his state, and he really must not," Isabel said. "He really must not."

"He certainly ought not," Gertrude said. "Susan, however . . . Miss Brennan, I really think you are the one best able to persuade him."

With a start, Alice realized that her presence was

known to the blind woman. "I've tried," she said. "As a matter of fact, IVe called the doctor."

"Doctor!" cried Isabel.

"Yes. Dr. FoUett."

''Child," Gertrude said in a moment, "child, what have you done?"

"Fve . . . called the doctor," Alice said in another moment. She kept her voice matter-of-fact, but she was getting angry.

"Oh, dear," said Isabel. "Oh, dear. Oh, dear."

"We do not call Dr. Follett," Gertrude said. "Never. You ought to have asked. He can't be coming. Not here."

"But he is coming," Alice mamtained stoutly, "or so he said. And I'm sorry, but I do not understand."

"No. Of course, you couldn't," said Gertrude with surprising indulgence. "Nevertheless it is . . . well ... Of course"—she drew herself up stiffer if possible— ''we did not call."

"If he's coming," said Isabel, "we must warn Maud."

"Where is Maud?"

"I haven't the famtest idea," said Alice. "Nor have you the faintest idea how annoying all this mystery is to me." She spoke angrily. Then she held her breath for their reaction.

Isabel's eyes shifted. "My dear Alice," she complained, "it's so awkward. Of course you couldn't know, my dear. When Maud was younger she and Dr. Follett. . . Well, he was her suitor. . . ."

"Dr. Follett," said Gertrude in her cool tinkling voice, "went away on what we supposed was a vacation. He married another woman and brought her here to Ogaunee. Of course, we have had no communication with him since."

"I see," said Alice gravely, although she wanted to laugh. "How long ago was this. Miss Whitlock?"

"It was in 1917," Gertrude said, as if time stood still for her and this was just the other day.

"But what do you do for a doctor?"

"Oh, Dr. Gunderson is only eleven miles away," said Isabel. "Really, Alice, you ought to have asked. How dreadful for Maud, for all of us."

Maud was approaching through the dining room. That tread, at once quick and heavy, was the unmistakable con-

comitant of her waddling gait. She came through the door in a moment, shapeless in a dark cloak. She too, had been out of doors. Alice idly wondered where and why.

Isabel spoke to her on the swift fingers of her only hand. Alice watched the pale heavy face, waiting for news to seep through to whatever brain worked behind those little pig eyes that blinked once or twice, but remained fastened on the fingers. She saw the face change, grow sly. The loose hps fell open in a queer smile. The eyes sharpened. Surely the expression was that of anticipation and imholy joy.

Maud said, in her chest tones, "Is that so?"

Isabel's hand worked madly.

"Aw, let him come," said Maud.

"She must not see him," said Gertrude sharply. "She must go upstairs at once." Her voice rang with command. Maud looked planted there on her two Siick stems. Gertrude struck her on the shoulder with her forefinger. Her blind face was imperious.

Then came the doorbell, and the three sisters scuttled out of the hall. Gertrude picked up her skirts and sailed through the parlor toward her own room, with majestic certainty and uncanny speed. Isabel climbed the stairs, pushing Maud before her. Maud, who went up with her face turned backward, reluctant, thoroughly uncoy, per-fecdy wUling to risk an encounter with the man in her life. But she let Isabel hurry her past the table that stood just behind the railing on the edge of the stairwell, and around the comer of an upstairs wall.

They were gone. Alice stood alone, at the foot of the stairs, half exasperated, half relieved.

Dr. Follet was about sixty years old, she guessed, a dignified and rather pordy fellow with a bald head and gold-rimmed eyeglasses. His face was pink and talcumed. His neat tan suit was smooth over his robinlike contours. He sent forth a faint clean aroma, antiseptic and comforting. He acted as if he had resolved to do his duty precisely.

He kept his eyes on her face and his head nodding while he listened to her account of the disaster that had overtaken Innes Whitlock. He said, when she had finished, "Thank you, Miss Brennan, that's very helpful. Now where is the patient?"

Alice knocked on the sliding doors and then began to draw them back. Someone helped from the other side. It was Fred.

Innes was still lying on the sofa, looking very pale, scarcely able to Uft his head. His mother sat in a chair, pulled up close, and she now rose to make room for the doctor.

"Ah," said Dr. Follett, "how are you, Susan?"

"Oh, I'm fine," she said. "Just fine. And you, doctor?"

Again Alice felt imreasonably lonely to be left out of a whole world of people who kept saying, "Fine. Just fine," to each other.

Fred had gone. "Would you rather I went away?'' asked Alice.

"No, no," Innes said. "Doctor, this is Miss Brennan, my fiancee."

"Ah," said Dr. Follett, "she told me she was your secretary." In here, safe from the Whitlock girls, he was less businesslike. He looked benignly at Alice through the upper half of his glasses.

"The thing is that I must get along to my camp, doctor," Innes said fretfully. "The object of this whole trip. I never meant to stop here at all. But now Alice has got it into her head to worry about me." Alice wondered who had told him. "Fred says she won't let me go until you've seen me. She's being very bossy." He used his httle-boy voice and his pout, but she realized that he was much pleased. The role of an anxious sweetheart hadn't occurred to her, but here it was, ready and waiting.

"Naturally," said the doctor. "And quite right, too. Now . . .''

Susan Innes Whitlock drew Alice to a far comer of the room. They sat down with their backs to the men. "Innes has been telling me. I'm so happy about you. I've hoped he would find somebody. And I do think you were very wise to make him see the doctor."

"Thaitk you," said Alice, feeling a little ashamed. "But IVe upset his sisters."

"Oh, dear me, I'd forgotten." Susan looked concerned. "But I'm glad," she said, "and I think you were right" She patted Alice's hand with a kind of indignant support "Why did Fred call you Mrs. Innes?" blurted Alice. "If I shouldn't ask, please just say so. But rU go on making mistakes if I don't ask questions."

"Of course," said Susan sympathetically. "You must be wondering. It's only because they are the Misses Whidock, you see, and after their father died and I moved into the cottage. . . . Well, it seemed better not to confuse everybody."

Alice shook her head as if to convince herself that this explained anything.

"It's hard for you to understand, I know," Susan said. "But they never thought I quite measured up to Sophia, you see."

"Why not?" said Alice bluntly. "Because I was in service here." "Oh."

Susan's eyes, that had been watching, relaxed into thoughtfulness. "Stephen always did exactly as he pleased, but I'm afraid it was pretty hard on the girls. They had just come back from Europe, too." She sighed. "Well, that was long ago."

"I wish Innes had taken me to your house," Alice said impulsively.

"I wish so, too. Perhaps he will, someday. Or, at least you must come."

There it was, something unsure, between Innes and his mother. But Ahce liked her. Her instinct was stubborn about that.

Now the doctor was helping Innes to his feet. "He says," called Innes in a pleased voice, "that I will be just as imcomfortable in the car as anywhere else. So we'll go along."

"Is it really all right?" Alice was anxious. "I think so," the doctor said. "He has gotten rid of whatever poisoned him. He will feel weak, of course. And he had better stick to liquids for a day or so. He tells me

"Tell Fred, will you, dear?" Innes wobbled. "Good-by mother."

Alice watched them. Susan patted his sleeve, reaching out from a little distance, as if she dared not come closer. Innes was uncomfortable. Alice already knew him well enough to be sure of that. He was not at ease with his mother.

Alice went with the doctor out into the hall.

Fred was there. "You can put my bag in the car," she told him. "We're going ahead."

Her bag was already at his feet. Fred picked it up and went out

The doctor said, "Good-by, Miss Brennan."

"I'm grateful to you for coming," Alice said, "and I must apologize if I've embarrassed you. I didn't know. But I'm very glad you came. And I do thank you."

The doctor's eyes showed an imexpected twinkle. "Quite all right, Miss Brennan. Ill send a bill." He looked slyly around the hall. The velvet curtains to the parlor had been drawn, covering the opening and shutting them in. "Where are they?" His lips barely moved.

Alice shrugged and felt her dimpb surge into her cheek as it did when she suppressed a smile.

The doctor said, "Well, this has been an adventure. Now I think I'll just take Susan home."

Susan and Innes came through the sliding doors. He walked without her help, but he looked ghastly. "I think .. ." he said, ". . . excuse me."

He wobbled off down the hall. There was a bathroom back there, across the far end of it, connecting both into the hall and to Gertrude's room, behind the parlor. Innes went in and closed the door.

"Good-by, Alice." Alice kissed her mother-in-law to be. The old lady's cheek was soft and fragrant. Dr. Follett gathered Susan under his wing and left.

Alice looked up the stairs. Beyond the railing up there she could see only the table and the big old-fashioned kerosene lamp with the flower-painted china shade that stood on it. No one was visible. The velvet curtains hung straight at her right. All was quiet. Dignified, haughty, withdrawn, invisible, the three Whitlock girls made no sign.

She picked up her hat from the hall table and turned to the mirror. She heard Fred outside; she heard the bathroom door open, and Innes's footsteps, sounding firmer. Then Fred was in at the front door. Still looking at herself in the glass, Alice knew quite well that Innes was part way down the hall to her left and that Fred was close to her, at the right. That the comings and goings were part of the rhythm of their departure. She felt no alarm, nothing.

But the hall exploded with soimd and movement. She felt Fred move like a streak, heard him cry out, and then crash. She turned to see Innes huddled against the dioing-room wall with Fred's body holding him there, and the ruins of the big kerosene lamp scattered on the floor. A broken piece of the china shade gyrated slowly toward her and settled down at her feet. For what seemed like minutes, they stood as if they were all paralyzed in their places. Then Alice ran, stumbling, toward the men.

"Hang onto him, will you?" Fred took the stairs two at a time. Alice put herself where Fred had been and heard Innes's breathing, loud and gasping and broken in rhythm.

"Are you hurt? Did it hurt you?"

He couldn't answer except by shaking his head ever so slightly.

Fred came pounding down. "Nobody up there. What the hell happened?"

"It fell," Alice said stupidly.

"I don't see how it could."

"But it fell."

"Did you hear anything?"

"I heard it fall."

"No. Afterward?"

Alice shook her head. "What do you mean?"

"I dunno," Fred said uneasily. "I thought ... it was upstairs."

They were talking fast, almost in whispers. Now Innes stirred.

"Is ever3rthing in the car?" he said with sudden strength.

"You'd better rest," warned Alice. "Good heavens, that was an awful shock. I . . . I'm shaking."

Fred kicked the metal lamp base.

"Doctor," Alice said to him, aside, and he gave her a look and went swiftly away.

Alice wished afterward that she had not urged Innes back into the sitting room, but she did, and got him seated. She was afraid he might be sick again, but color had come back to his face and he looked somewhat better.

"What on earth"—Gertrude was holding her hand to her heart in the dooray—"crashed so? Innes, are you there?" She seemed to have lost her sure sense of her surroundings in the excitement.

"It was the lamp falling," Alice said. "It's all right. No one was hurt. Miss Whitlock."

"What a dreadful crash!" she said.

"The lamp's broken." Isabel stood beside her, edging, with her tendency to go sidewise, through ahead of her. Her complaining voice seemed to hold a little anger. "Mama's big lamp from the upstairs table. I was in the kitchen. Josephine has gone out!"—as if this were outrage. "What happened, Alice?"

"I really don't know. Miss Isabel," Alice said shortly.

"Innes . . . ?"

Innes said, "It didn't hit me. So it's aU right."

"What's going on?" Maud's masculine tones broke in upon them. "Say, who busted the lamp? It's all over the floor."

Everybody shrugged.

Maud looked at Innes with her sly little eyes. "You feeling better?" she said.

"I feel much better," Innes said vigorously. "A little shock like that seems to have been just what I needed. Where's Fred? I feel much stronger. We must go."

"He . . ." Alice began and stopped, for Fred was back; and since he told her with a glance that he had missed the Doctor, she saw no reason to upset the Misses Whitlock again. "Here he is, now. But are you sure you're all right, Innes?"

"Yes," said Innes, "I'm all right."

Josephine came into view in the hall, wearing her coat, with a newspaper-wrapped package held across her body like a shield. Stie looked dazed.

"Where have you been?" wailed Isabel.

But Innes got jerkily up and blundered across the room.

''Good-by, Gertrude, Maud, Isabel. Thanks for everything. I'll write you. But remember"—he spoke rapidly as that he can be quite comfortable at this camp. And you will be with him, Miss Brennan."

"Yes," said Alice doubtfully. She felt unselfish devotion was being put upon her.

if to get this said before his strength failed—"about the accounts. I meant that. I'll send a man up from the office. He'll go over everything with you. Mind you show him everything. And I must have your powers of attorney. Thanks, agam. Good-by."

Alice said, "Good-by." She smiled valiantly at Isabel and Maud. Gertrude's hand she pressed briefly. It was a sketchy leave-taking on her part, and although she seemed caught up in Innes's fervor to get away and therefore rushed and pressed by his hurry, the brevity of her farewells was her own idea.

She felt she'd had enough of the Whitlock sisters.

The Whitlock girls did not stand on the doorstep to wish their guests Godspeed. The tall front doors closed. The tall facade was a pale mask in the dark. Fred helped Innes into the tonneau and wrapped him well.

"The air in your face, sir?"

"Yes, that would be good."

Fred turned down the window. Alice felt rather useless. ''Shall I sit in front?" she said, "You want to be quiet, don't you, Innes?"

Innes seemed too exhatisted to do more than murmur consent. But it was consent. He seemed more himself, even in this collapsed state, than he had seemed at any time in his sisters' house. At least he was Innes Whitlock, who knew he didn't want to talk. There he had not been himself nor anything else, but a man looking for a role to act and not finding it.

The car moved away softly, a cradle on wheels for its master.

"She seems to be running sweet again," Alice said. "What was the matter with her, Fred?"

"You wouldn't know if I told you.''

"No. I suppose I wouldn't." Her mind was somewhere else already. "Do you know, Fred, you moved awful fast in there. You were quite a hero."

"Nuts," he said.

"Maybe you saved his life."

"Look," he said, "if you see something's going to faU on somebody unless you push them, you push them. It's a reflex."

"A what?"

"What the hell?" Fred said. Alice wiggled herself back in the seat as they drifted gently down the hilL

"How do we go? Over that pit?"

"Yup. Have to, to get on number six."

"I hope we go over it faster than we came." Alice shivered.